Zichen Wang joins ChinaFile Conversation: Chips and Soybeans

What is the state of play now? Is the Trump administration achieving its stated trade goals with China? Which country has the upper hand in negotiations?

Zichen Wang, Research Fellow and Director for International Communications, just joined the latest ChinaFile Conversation published on September 30, 2025, together with Dexter Tiff Roberts, Wendy Cutler, Zack Cooper, Ali Wyne, Paul Triolo, Fred Gao, and Martin Chorzempa.

ChinaFile is an online magazine published by the Asia Society, dedicated to promoting an informed, nuanced, and vibrant public conversation about China, in the U.S. and around the world.

The ChinaFile Conversation regularly brings together a group of contributors to discuss and, often, to argue over recent China news.

Chips and Soybeans

American and Chinese officials announced on September 15 that they had reached a “framework agreement” on the future of TikTok. On September 25, Trump signed an executive order approving the framework agreement for the TikTok deal, although Chinese communications on it have been much more vague. And whatever happens with TikTok, there are many other tensions that remain unresolved:

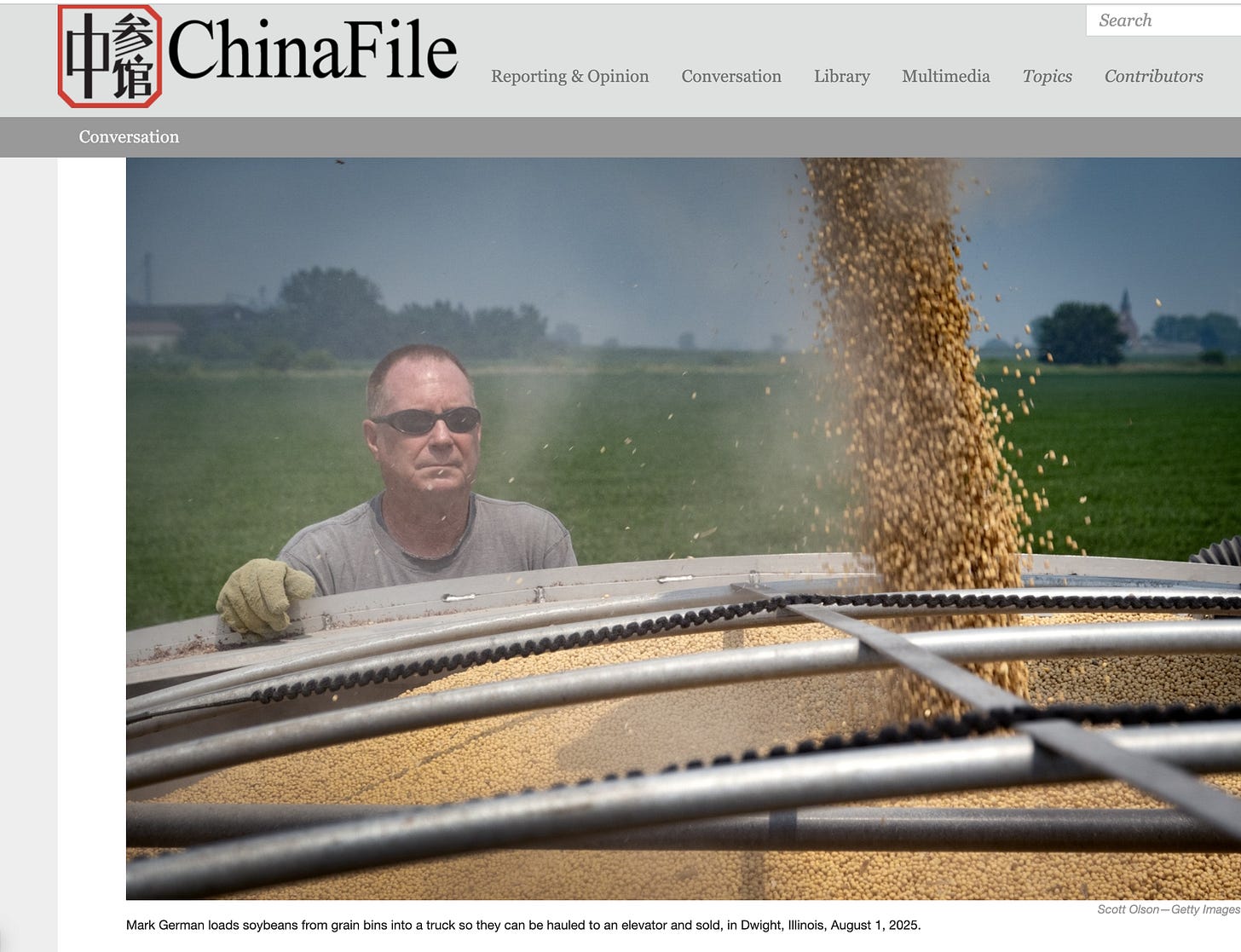

“U.S. farmers are missing out on billions of dollars of soybean sales to China halfway through their prime marketing season, as stalled trade talks halt exports and rival South American suppliers step in to fill the gap,” according to Reuters.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has once again told Chinese companies not to buy Nvidia chips.

China’s export restrictions on rare earth minerals remain in force.

Tariffs of 145 percent are set to take effect in November.

What is the state of play now? Is the Trump administration achieving its stated trade goals with China? Which country has the upper hand in negotiations? —The Editors

Comments

Dexter Tiff Roberts

Want a snapshot of the U.S.-China trade relationship? Take a look at one recent day.

On Thursday September 25, President Donald Trump issued an executive order approving a TikTok deal and saying TikTok had met the conditions as set forward in the bill passed by Congress and signed by former President Biden last year. What are those conditions? That parent company ByteDance will sell off its majority share and TikTok will no longer be a security risk for Americans.

What else happened that same day? Well, for starters, China said nothing to confirm any TikTok deal. And Beijing announced that it had put six more U.S. companies on its sanctions list: three for doing business with Taiwan’s military added to its entity list and three put on an export control list for actions endangering China’s national security.

You could be forgiven for getting whiplash watching the twists and turns of the U.S.-China relationship. But the bigger picture emerging shows a pattern: A lot of giving by Washington and tough responses from Beijing.

To whit: Trump earlier blocked Taiwan’s president from doing a stopover in the U.S. More recently, he halted arms sales to Taiwan. And he dialed back tech controls on China by allowing AI chip company Nvidia to sell chips to China.

Then there’s the way that Trump talks about President Xi. He’s referred to him as “brilliant,” says that he respects Xi and that he considers him a “friend.” He’s also praised him for his “iron fist”!

For its part, Beijing has said Nvidia had violated China’s anti-monopoly law and has ordered its companies to stop buying its products. Talk about looking a gift horse in the mouth!

And Chinese companies continue to buy soybeans from Brazil and Argentina, much to the chagrin of America’s struggling farmers.

If it seems pretty obvious who has the upper hand in the relationship (and it does seem obvious), why would Beijing be bending on TikTok as the Trump administration has said they are ready to do? Remember, not too long ago, Beijing insisted that ByteDance, the parent company, would never sell off its majority share in TikTok.

You can be very sure that Beijing is expecting a lot in return if it allows the TikTok deal to move forward on Trump’s terms. There is no doubt that Beijing right now is putting heavy pressure on Washington to further loosen advanced technology controls.

More alarmingly, Beijing very likely is telling Washington that they expect the U.S. to adopt a softer level of support for Taiwan, in China’s favor.

And then there’s the possibility that China may push for a deal that ends up giving parent company ByteDance a larger role than Trump has suggested, as Reuters reported on Friday.

It seems pretty clear that Beijing is in the driver’s seat as Trump pursues his holy grail of a state visit in Beijing and a big deal to go with it, expected to happen early next year. (He and Xi will first meet on the sidelines of APEC next month.)

Wendy Cutler

The recent framework deal on TikTok is an important step in resolving one significant irritant in the U.S.-China economic relationship. But, many other matters require attention if both countries are going to successfully stabilize the bilateral trade and economic relationship, including critical minerals and magnets, excess capacity exports, agriculture market access, and level playing field concerns in a wide array of sectors.

Following his recent call with Xi Jinping, Donald Trump noted progress not only on TikTok but on trade in general. He also confirmed his plans to meet Xi on the margins of the APEC meeting in Korea, and possible reciprocal visits to each others’ countries in 2026. With the United States chairing the G20 next year and China hosting APEC, there will be multiple opportunities for officials at all levels to meet.

These potential leader-level meetings and visits are important action-forcing events that can help produce outcomes on relatively low-hanging fruit, but also on matters that seem intractable. But to succeed, it’s important for the Administration to think beyond the APEC side meeting on what it wants to achieve with China. It should also revisit its 90-day tariff pause policy, which is losing its credibility as leverage.

In its dealings with Beijing to date, the Administration seems to be focusing on immediate problems—including reaching a deal on TikTok, securing access to Chinese critical minerals and magnets, and requesting China to reverse its boycott of U.S. soybean purchases. Make no mistake: All of these efforts are valuable. But cobbling together short-term wins and calling this a trade deal is off the mark.

Ask Ambassador Robert Lighthizer, President Trump’s U.S. Trade Representative during the first term. He skillfully led the U.S. team negotiating the Phase One deal with China. While many just recall the Chinese commitments to purchase huge amounts of U.S. agricultural products, energy, and other goods, the agreement featured over 50 pages of commitments, largely by China, on technology transfer, agriculture market access, and intellectual property protection. There was also agreement to launch a Phase Two negotiation, although it never got off the ground. The Phase One agreement ultimately did not succeed in rebalancing the trade relationship, but it did make inroads in getting certain Chinese policies and regulations on a better track.

However, China also learned important lessons from the Phase One negotiation, which has made it a much more formidable and confident negotiating counterpart this time around. With a strategic focus on self-reliance and diversifying its trade partners, China has reduced its dependence on the U.S. market in recent years, making it less vulnerable to U.S. tariff threats. It has shown its willingness to use its leverage against the U.S. by withholding important shipments of critical minerals and magnets. China has also put in place a number of policy and regulatory tools beyond tariffs to act against U.S. economic interests when it sees fit. That said, Beijing shares an interest with the U.S. in stabilizing our relationship and de-escalating tensions in practical ways.

Resolving immediate flashpoints in the relationship that can be announced by leaders is noteworthy. But it’s important to look beyond the late October Xi-Trump meeting and set out solid objectives for the bilateral relationship that can be the focus of American engagements with their Chinese counterparts during 2026, particularly in light of the forthcoming U.S. G20 and Chinese APEC leadership.

Zichen Wang

The asymmetry of TikTok’s importance to Washington and Beijing is striking. In China, TikTok—an offshoot of the domestic Douyin app—remains a short-video platform launched by private entrepreneurs with substantial American investment. It is not Huawei or even Xiaomi, firms rooted in the “real economy” of semiconductors and electric vehicles. Abroad, however, and particularly in the United States, TikTok has become deeply woven into everyday life. Its uncanny recommendation algorithm has captivated American users, while its vast trove of data and rising political salience have unsettled policymakers. No evidence has ever surfaced that Beijing has weaponized the platform, or even intended to, but suspicion alone has provided fertile ground for U.S. persecution. For Washington, TikTok has become strategic; for Beijing, it is at most a bargaining chip—yet one too high-profile to surrender without extracting something in return.

China therefore treads a delicate line. Its official readout of the recent meeting with U.S. officials in Madrid insists there is no compromise on principle, while approvals proceed according to Chinese law and “in line with the intentions of Chinese companies.” This formula preserves room for maneuver without signaling weakness—lest Beijing appear to produce a high-profile victim and thereby embolden ever more belligerent U.S. economic coercion.

The billion-dollar question is what China has gained in exchange. The Chinese summary described a framework agreement extending beyond TikTok to cover commitments on “reducing investment barriers” and “advancing relevant economic and trade cooperation.” U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent remarked that the U.S. side had agreed not to take certain actions: “So basically, what they got was the promise of things that won’t happen rather than taking things off.” As the official who would bear the political cost of appearing to concede too much to Beijing, he understandably downplayed concrete concessions. But the under-reported news is: Has the U.S. Treasury Secretary promised a sort of ceasefire in the trade war between the two largest economies?

Beijing extended gestures of goodwill during a phone call between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump on September 19. Xi highlighted America’s contribution to China’s victory in World War II—a symbolic olive branch responding to a grievance publicly raised by Trump. At the same time, China continues to withhold cards it knows Washington values, including purchases of American Boeing jets and soybeans, which China now explicitly ties to tariffs. Xi also voiced the hope that Chinese companies might enjoy an “open, fair, and non-discriminatory business environment” in the United States, echoing the language of its Madrid readout.

A wildcard is whether the TikTok framework could open space for renewed two-way investment. Pragmatically, U.S. reindustrialization could stand to benefit. Politically, even if Trump himself were receptive, whether he could overcome overwhelming political resistance is uncertain, despite his current power and discretion. His instinctive affinity for tariffs weighs against trade, yet investment flows could paradoxically reinforce interdependence at the very moment when “decoupling” has become conventional wisdom.

For those who regard renewed interdependence as the least bad outcome for both countries—and for the world—Trump, ironically, may be the most likely American leader to make it possible.

Zack Cooper

In my view, Beijing has clearly held the upper hand over the Trump administration in recent months. By cutting off rare earth magnet exports, Chinese leaders have convinced Washington that they hold all the cards. That perception is false—but it has fundamentally reshaped the bilateral relationship. Since then, President Trump has made a series of concessions to China, receiving little to nothing in return.

For months, Chinese officials have skillfully dangled the prospect of a summit with Xi Jinping in Beijing, using it to extract U.S. concessions on export controls and Taiwan. Most notably, Washington has loosened restrictions on semiconductors, including the sale of Nvidia H20 chips to China and suggested the potential to allow sales of more advanced B30A chips down the line. Meanwhile, China has ramped up pressure on Nvidia, likely to gain leverage over its CEO Jensen Huang, who appears to have substantial influence with Trump at the moment. On Taiwan, the Trump team has taken several steps desired by Beijing: effectively rejecting a transit by President Lai Ching-te through New York, halting a visit by Taiwan’s defense minister to Washington, and most recently, not approving a $400 million arms package.

The conclusion is hard to avoid: Beijing is playing Washington, and doing so with remarkable effectiveness. While other major economies have been forced to make trade concessions to Trump, he has spent the past few months making concessions to China. The administration has sought Chinese cooperation on fentanyl precursors and increased purchases of U.S. soybeans and aircraft—but Beijing has stalled, even refusing to finalize the much-touted TikTok deal. And by delaying the planned summit in Beijing, Xi is buying time to extract even more. China is showing its capabilities while biding its time, and that strategy is working.

Ali Wyne

U.S. President Donald Trump claimed in late August that the United States has “much bigger and better cards” than China, and that Washington could “destroy” Beijing by playing them. It would be premature to dismiss Trump’s contention as idle bombast: The U.S. economy is roughly $11 trillion larger than China’s, and the U.S. dollar accounted for an estimated 58 percent of the world’s disclosed foreign-exchange reserves at the end of last year.

Still, the Trump administration’s initial overconfidence in the capacity of tariff pressure to recalibrate bilateral trade relations has boomeranged to give China the upper hand in negotiations with the United States. Relative to “Liberation Day” on April 2, Beijing is more assured not only that it can absorb economic pressure from Washington, but also that it can extract economic and potentially even security concessions by targeting pain points of the U.S. economy. It threatened to bring the U.S. auto industry to heel with just a brief curtailment of rare-earth magnet exports, and its refusal since late May to buy soybeans from the United States poses a crisis for U.S. soybean farmers, who typically export around half of their annual harvest to China.

China’s economic leverage vis-à-vis the United States appears further pronounced when one considers the degradation of America’s diplomatic network. Despite the oft-heard proposition that the United States far outweighs China economically because of its alliances and partnerships, many of America’s friends are now seeking to de-risk from Washington. Even a successor to Trump who disavows his “America first” foreign policy would find it difficult to reverse that trend.

The good news is that a limited economic deal between the United States and China seems plausible. Washington might agree to further unwind some of the “unilateral trade restriction measures” that Trump’s Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, mentioned during their September 19 phone call. Beijing might agree to increase its imports of American products (potentially including soybeans and aircraft), crack down more vigorously on the export of fentanyl precursors, and even invest in battery plants in the United States.

The bad news is that a fundamental recalibration of economic ties seems unlikely: The United States believes that China seeks to overtake it as the world’s leading power, while China believes that the United States will seek to thwart its technological progress—and, by extension, its economic development—no matter who occupies the White House.

Even so, building on the Madrid talks between their respective teams, Trump and Xi should undertake to lay the foundation for a more sustainable bilateral relationship. While deep interdependence creates security risks for both countries, the continued unwinding of that phenomenon could weaken an important constraint on the outbreak of armed confrontation.

Paul Triolo

U.S. China relations have entered interesting and uncharted territory in the runup to a possible presidential meeting on the margins of the APEC conference in Seoul in late October. The landscape for negotiations around a potential trade and economic deal has been changed since April by a series of events, most notably China’s imposition of a global stoppage of shipments of rare earths and magnets and rollout of an export licensing system, the reverberations of which continue to perturb the relationship. U.S. officials have been loath to admit the impact of the licensing plan on the U.S. defense establishment, and have focused on getting Beijing to resume shipments of critical minerals and derived products to civilian industries such as autos, semiconductors, and consumer goods. But the specter of Beijing pulling back on these licenses will continue to be a feature of the relationship, and this is tempering the Trump administration’s willingness to undertake major expansions of export controls on semiconductors and related technologies. It is also forcing reconsideration of the massive number of controls rolled out by the Biden administration, which were rushed, sloppy, and did not have sufficient industry input.

As the export control drama plays out in the background on both sides, much of it shielded from public discourse, the other elements of the complex relationship are more visible, and some will need to be addressed in the eventual trade deal. However, it does not appear that any of the structural issues that were part of the first Trump administration trade deal discussions will be on the table. Instead, we are left with things like progress on fentanyl and purchases of agricultural products and some key technologies including Boeing aircraft. New flexibility on allowing some Chinese investment in electric vehicles and batteries in the U.S. could also be on the table. But as the inability of both sides to put together a sufficiently compelling package of deals that could have warranted a Trump visit to Beijing illustrates, the road to a major deal that moves the needle significantly in a more positive direction will remain challenging. Both sides distrust the other and continue to put in place incremental new controls to demonstrate that they have cards to play. Recent additions to the U.S. entity list and Chinese unreliable entity list and export control list illustrate this dynamic.

So what are we left with to anticipate? President Trump appears to really want a deal and a visit to Beijing, on his terms, while Xi Jinping is also eager for a Trump visit. Both want the visit to play to domestic audiences—Trump to show he can deal with China and get benefits for U.S. jobs and farmers, and Xi to show that he can manage the complex and contentious relationship with Washington. The durability of any deal, though, remains in question. Tough core issues such as Taiwan, export controls for Beijing, Chinese “overcapacity,” and beating China in the race to advanced AI all remain lurking in the background. Both sides frequently remind the other of these redlines.

My sense is that the AI issue is likely to be the most knotty to make progress on. Major constituencies in Washington are hell bent on slowing the ability of Chinese companies to train advanced models, while Beijing views AI as a critical enabler of future economic growth. Both sides will dance around the issue of how far export controls can or should be rolled back to accommodate a trade deal or force movement on the rare earths issue. When U.S. defense contractors start cutting back production of critical weapons systems due to lack of Chinese rare earths magnets, we could have another major crisis in the relationship, depending on the breadth and depth of the trade deal being hammered out. The Trump administration has yet to really define either a China or Taiwan policy, and after the transactional phase, all the structural issues and redlines will continue to make whatever truce is reached fragile.

Fred Gao

China-U.S. trade and technology negotiations are currently at an unstable stalemate. This is exemplified by the two sides reaching a basic “framework” consensus on TikTok during their talks in Madrid and then the September 19 call between their two heads of state. However, ByteDance still needs to engage in further commercial negotiations with the U.S. side, and if these negotiations drag on for too long, the Trump administration may lose patience, increase pressure, and undermine this fragile consensus.

Concurrently, China’s official readout of the call showed considerable goodwill toward Donald Trump. Unlike previous communications earlier this year, the official statement did not use phrases such as “at the request,” as the readout from the leaders’ previous call did. Additionally, Beijing specifically emphasized and expressed gratitude for the U.S.’s assistance to China during World War II, a gesture to ease U.S. concerns regarding China’s Victory Day military parade.

Notably, unlike the Phase One trade agreement, the two sides did not pursue a grand and comprehensive trade deal this time. Instead, they prioritized reaching consensus on relatively simpler issues such as TikTok. On the one hand, this reflects a pragmatic “low-hanging fruit first” strategy adopted by both sides. On the other hand, it also indicates Trump’s urgent need to achieve visible results in negotiations with Beijing to claim a “win” to his domestic voters. Consequently, regarding more contentious and harder-to-resolve core issues such as tariffs and technology containment against China, Trump has adopted an ambiguous stance to avoid a complete breakdown in negotiations.

Throughout, China has maintained a consistent position in the talks: It is willing to resolve differences with the United States through dialogue and consultation but firmly refuses to yield to the “maximum pressure” tactics often employed by Trump. During the recent call between the heads of state, Xi Jinping also emphasized that the U.S. should cease its unilateral trade restrictions to avoid undermining the progress achieved through multiple rounds of consultations. Given the current situation, it is possible that both sides may extend the existing tariff truce to allow more time for further negotiations.

This stalemate is further underpinned by the challenges facing one of the Trump administration’s key objectives in economic negotiations with China: to achieve U.S. “reindustrialization.” The core logic is to combine high tariffs on China with domestic tax cuts and manufacturing investment incentives, thereby raising import barriers and boosting the attractiveness of domestic production. In reality, however, U.S. small and medium-sized enterprises that depend on global supply chains have seen their competitiveness decline as tariffs drive up raw material costs. In addition, U.S. labor cannot quickly adapt to the skill requirements of manufacturing jobs, and labor costs remain high, which limits the effectiveness of both tariffs and tax incentives. As a result, when faced with steep tariffs, many companies have shifted production to Mexico and Southeast Asia to diversify risk, rather than reshoring to the United States.

Martin Chorzempa

American AI chips have faced a pincer movement of export bans from Washington and now import bans from Beijing. In both capitals, the approach to technology controls and fate of interdependence are now highly uncertain. In semiconductors, the U.S. controls important chokepoints that China wants to work around, while in critical minerals, the U.S. wants to reduce dependency on China.

After initially banning tuned-down AI chips like Nvidia’s H20 that were designed to comply with Biden-era export controls, President Trump and other high-level U.S. officials have reversed course and questioned the effectiveness and costs of past controls as part of a broader suspicion of Biden administration actions. Instead, the U.S. is focused on “diffusion” of American A.I. chips around the world, including an explicit attempt to keep China “addicted” to U.S. chip technology rather than going all in on indigenization.

Congress and many security hawks are critical of this approach and want to even more tightly restrict China’s access to computing power, but their ability to push the administration to retain and strengthen controls seems limited at best. Importantly, the Trump administration has not yet lifted any of the export controls that were imposed by the Biden Administration, but has only canceled the A.I. diffusion framework that would have created global controls on chips, and which was not even in place yet.

Meanwhile, Chinese authorities have banned Chinese AI firms from buying American AI chips. Considering the limited supply of domestic chips and the disruptions involved in shifting away from Nvidia hardware and software, the move suggests Beijing may be increasingly willing to trade off short term benefits to Chinese A.I. capabilities for longer term goals of developing a fully domestic AI ecosystem. But it may also be a negotiating position to pressure the U.S. to permit exports of much more powerful chips to China.

If the U.S. and China can reach a “grand tech bargain,” lifting chip controls will probably still be a key Chinese ask, as will removing controls on high bandwidth memory chips that Huawei needs to make its own AI chips. China has not yet put anything of commensurate strategic value on the table that it could provide in return, and Secretary of the Treasury Bessent has signaled that Chinese investment is not on the table as an ask from the U.S. side. Loosening the controls on memory in particular would be counterproductive to the administration’s goal of extending Chinese dependence on U.S. chips by loosening one of the major constraints on Huawei’s capacity to make homegrown AI chips that could displace U.S. chips in China’s market. In addition, there is little chance that Beijing will trust the durability of any deal for broader tech rapprochement enough to give up its drive to reduce dependencies on the U.S.

This Asia Society sounds like a propaganda arm of Washington. I wonder whether this kind of content is really worth publishing. It’s OK, I will unsubscribe.