Transcript: Kishore Mahbubani in Dialogue with Henry Huiyao Wang

Kishore Mahbubani bridges memoir and geopolitics at the Chinese launch of Living the Asian Century.

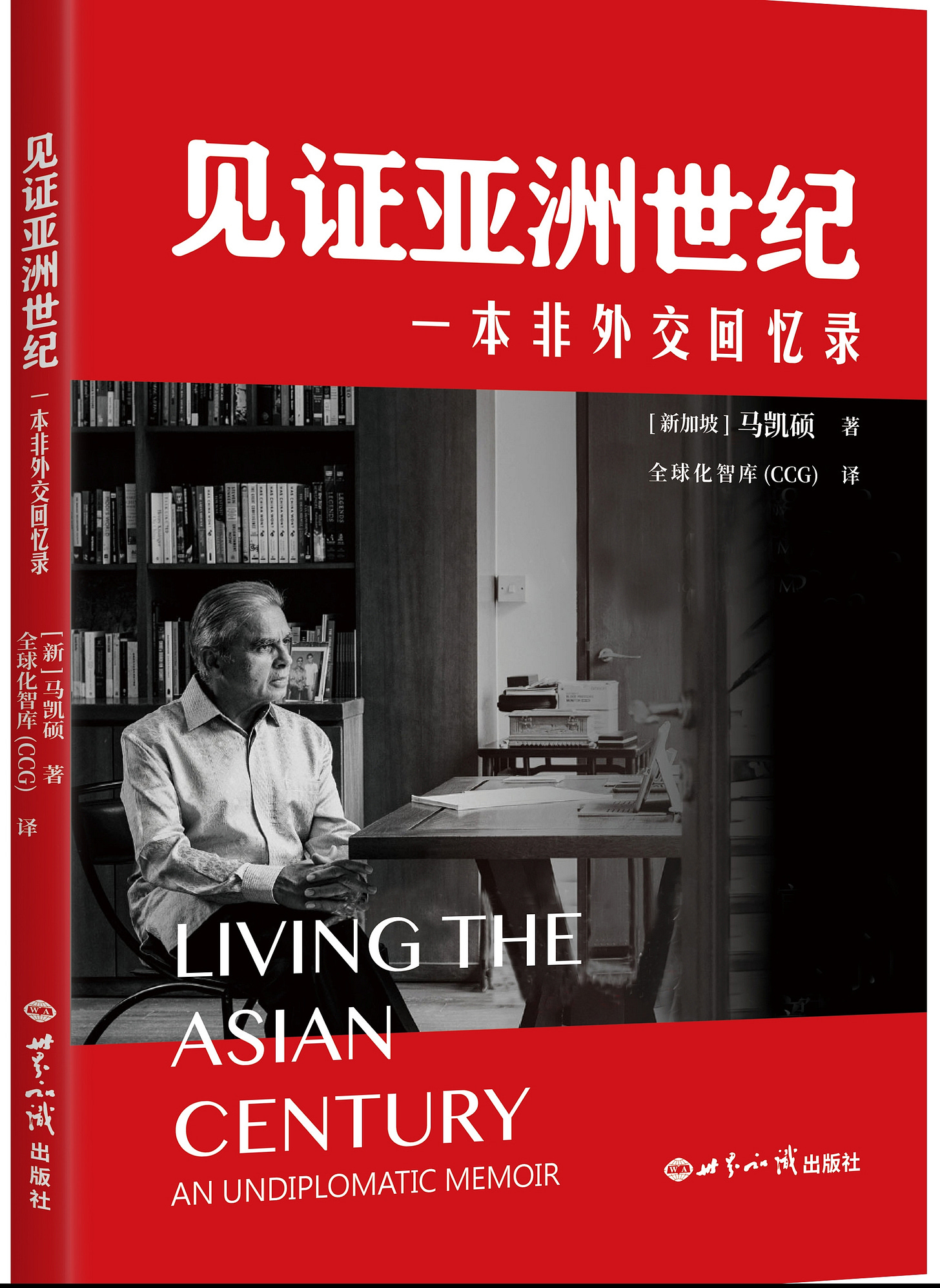

On November 3, 2025, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) hosted a book launch to mark the release of Kishore Mahbubani’s new book, Living the Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir (Chinese edition).

Kishore Mahbubani is a Distinguished Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, and the founding dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. A career diplomat turned academic, he spent 33 years in Singapore’s Foreign Service—twice serving as UN ambassador and as President of the UN Security Council (Jan 2001, May 2002).

This event builds on CCG’s long-running collaboration with Mahbubani, including co-publishing the open-access The Asian 21st Century with Springer Nature, which has recorded 4.22 million downloads worldwide and facilitating its Chinese edition. CCG also translated the Chinese edition of Has China Won? and supported the Beijing launch of the Chinese edition of The ASEAN Miracle.

The session featured Mahbubani’s reflections on his personal journey, followed by a dialogue with Henry Huiyao Wang, CCG President, and a live Q&A session involving Pakistani and Mexican ambassadors to China.

The event was broadcast on Chinese social media channels. The video recording remains available on CCG’s official WeChat blog and YouTube channel.

The following transcript is based on the video and has not been reviewed by any of the speakers.

Keynotes

Henry Huiyao Wang, President, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG)

Ambassador Kishore Mahbubani, distinguished excellencies, dear guests and journalists, and all the representatives of international organisations, companies, and media, a big welcome to CCG.

We’re very pleased to welcome all of you to this book launch event with the Center for China and Globalization. We’re going to share Professor Kishore Mahbubani’s latest book, his undiplomatic memoir, Living the Asian Century, with all of you. We hope we’ll hear Kishore’s keynote speech later, and we also look forward to our dialogue. Professor Mahbubani is a firm believer in and a key promoter of the Asian century. Having grown up in poverty in the 1950s in Singapore, he uses his memoir, Living the Asian Century, to chronicle not only the Republic of Singapore’s transformation from a poor economy into an Asian powerhouse, but also his own journey from a poor childhood in a multi-ethnic neighborhood to an illustrious diplomatic career that took him far and wide—from the desk of the Minister for Foreign Affairs in Singapore to the corridors and marble halls of the United Nations.

Kishore Mahbubani is both a witness to and an active participant in the story of Asia’s return to the centre of the world. I believe his life story is compelling and inspiring, particularly in these times. As a matter of fact, we credit him with VOA, a new term meaning the Voice of Asia. That’s the new name we have given to Kishore while he is in Beijing this time.

CCG was very honoured to take on the task of developing a Chinese edition. We have translated and edited this Chinese-language edition of the book, and we are very pleased to promote its Chinese launch and publication. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to the publisher, World Affairs Press, affiliated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, for publishing this book. The support from the CCG team was invaluable in bringing this book to publication.

I believe the Chinese edition will gain wide attention again in China this time. Living the Asian Century is the third book that CCG and Professor Kishore Mahbubani have collaborated on together. We previously published a book with Springer Nature, The Asian 21st Century, which is part of the China and Globalization book series. This book has become a global publishing phenomenon in international relations, as it has already been downloaded 421 million times since its launch two or three years ago—10, 20, even 30–40 times more than an average academic book. It is truly remarkable.

We have also translated The Asian 21st Century and Kishore’s other major work, Has China Won? into Chinese, which has attracted broad attention both at home and abroad. The Chinese editions have already sold tens of thousands of copies throughout China. They have become hot topics of discussion today, as we are seeing major advances as well as a tense geopolitical climate, both of which have brought attention to Kishore’s books.

Living the Asian Century, however, is also a more personal account. We’ve seen many grand narratives and big stories that Kishore has talked about, but this one is more personal, more down-to-earth, and more concrete about his own experiences. I believe that the three books CCG has helped publish in China will help our audience gain a more comprehensive understanding of the topics covered.

Personally, I’m truly honoured to welcome you back to CCG, Kishore. I have known you for nearly two decades. You are, of course, the founding dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School, and you have had a very impressive career in both the public and private sectors.

One of my most memorable experiences with you was in May 2019, when we debated side by side at the world-famous Munk Debate in Toronto, Canada—a main-stage event with about 3,000 participants. We faced H. R. McMaster, the former U.S. National Security Advisor, and Michael Pillsbury of the Hudson Institute’s Center on Chinese Strategy in 2019. Fortunately, we managed to win that very credible debate, even though winning wasn’t the main point.

Also, thanks to Kishore. Debating together was a great honour and very memorable. So that’s why I want to warmly welcome Kishore again. I know you have an excellent book to launch today. I’d also like to invite Kishore to give a formal talk about his book. And I know you have many fans in China, and the international audience is also very well represented.

Today, we have a full house, and you can see we have a number of ambassadors, international representatives, embassies, as well as companies, media, and academic and think tank representatives. It’s a great honour. Kishore has had a wonderful life and experience across two careers: diplomacy and academia.

In diplomacy, he was in the Singapore Foreign Service for 33 years, as you note in your book. He served twice as Singapore’s Ambassador to the United Nations and served as President of the United Nations Security Council, which is a great honour—I recall one of his outstanding speeches delivered while serving as Singapore’s Ambassador at the UN. He also began his academic career in 2004 as the founding dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. In fact, Dr Mabel Miao, our co-founder, is currently conducting research as a senior fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School for a few weeks. In 2019, Kishore was elected an International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

So, without further ado, I would like to give the floor to Kishore to speak about your excellent career experience, and particularly about this book. Please give an opening speech, and then we can follow with a dialogue. Welcome, Kishore.

Kishore Mahbubani, Distinguished Fellow, the Asia Research Institute (ARI), National University of Singapore (NUS)

Excellencies, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen,

It’s such a pleasure to be back at the Center for China and Globalization. I consider it my second home. I’ve been here many times, launched several books, and I’m very grateful, Henry, that you, Shirley, and your colleagues are hosting me now to launch this book too. What I propose to do is that I will, in the time given to me, try to give you a brief summary of this book. After that, hopefully, Henry, we can have a dialogue and maybe respond to questions too. I thought the best way to give a summary of this book is to say that it captures the story of my life with the five “D” words:

Number one, Deprivation. Number two, Dissent. Number three—you all know it—Diplomacy. Number four, Deanship. Number five, Discovery. These are the five phases of my life, quite different, actually.

You’ll see this when I begin to describe chapter one of my life: Deprivation. In fact, the first chapter of the book is called “Born Poor,” and then the second chapter is called “Still Poor.” I can honestly say that I did grow up in a very poor family and in a very poor Singapore then. Singapore’s per capita income then was about $500, the same, I think, as Ghana in Africa. I happened to live in a one-bedroom house with five of us, and my father kept losing his job all the time. But, as I say in my book, I don’t blame my father. He was orphaned at birth—his parents died within the first year he was born—so he was never brought up by his parents. At the age of 13, he was sent from Sindh to Singapore and, without any parental supervision, lived in what was then a very poor Singapore, accumulating the bad habits of smoking, drinking, gambling. As a result, frankly, life dealt him a very bad house of cards.

And when he had an arranged marriage with my mother, my mother had no clue that she was marrying somebody who was, you know, drinking, gambling and all that. And so my mother actually had a very rough life also in Singapore, coping with all this poverty. In fact, when I went to school at the age of 6, I had to be put on a special feeding program because I was technically undernourished. Now, as you can see, I’m overnourished. But it was a rough life. We didn’t have a flush toilet in our house till the age of 13. We had debt collectors coming to our house to try and collect debts from my father. And my father would roll under the bed and say, Tell the debt collector, say he’s not at home, you know.

So I had literally a very rough life as a child. But looking back now, paradoxically, when I look at the face of deprivation of my life, which probably lasts the first 20 years or so, I realise actually the deprivation was a gift to me. It was a gift, one because, as you know, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times read my book and actually gave me a very generous endorsement. And he said, Kishore, the real hero of your book is your mother, because my mother survived my father going to jail, the separation. And she brought us up, and she, you know, made us into a successful family. So when I watch my mother’s resilience, I told myself all through my life, like everyone else, I had my ups, I had my downs. But whenever I went down, I would just tell myself, my mother went through worse. She didn’t break down. How can I break down?

So that gift of resilience my mother gave me was probably the biggest gift I ever had in my life, and I would never have had it if I hadn’t gone through all the deprivation. But, you know, luckily, Singapore was developing. I went to school, got bursaries, and got scholarships at a very young age.

One of the most wonderful things that happened to me was that I accidentally discovered a public library—accidentally. Walked in there and saw the books. There were no books in my house, by the way. My father never read books. My mother never read books. We didn’t know what a book was. But then I discovered this public library, and I began to borrow books, and just fell in love with reading. I must have read four to five books a week as a child. And I think that’s what saved me at the end of the day—the love of reading basically opened all kinds of doors. And that resulted in me basically getting something spectacular in Singapore: the President’s Scholarship.

That President’s Scholarship is very important because when I finished high school, I started work as a textile salesman. All Sindhi boys like me would end up being textile salesmen. So I was working as a textile salesman selling cloth by the yard for 150 dollars a month. Then the President’s Scholarship came along and gave me 250 dollars a month. So my mother said, “250 dollars is more than 150 dollars, so why don’t you go to university?” and that’s how I ended up going to university. Complete accident, right?

And then, of course, university led to four of the best years of my life, which were spent at the university. But the reason I call that chapter of my life “Dissent” is because that’s when I discovered the art of questioning and challenging everything. It went to a remarkably high level because there was one year when Mr Lee Kuan Yew, then the prime minister of Singapore, came to the National University of Singapore, where I was studying. He was then an incredibly powerful and fierce prime minister. And when he was at the university, one of my philosophy professors was questioning him a lot. Mr Lee Kuan Yew got tired of that questioning and told the chairman—another student, his name was Arania—“Mr Chairman, let’s move on to the next question. No, no more questions from this person.”

But the chairman was a very young, brave Indian boy, Arania. He looked at Mr Lee Kuan Yew, and he said, “I am the chairman. I decide. So carry on questioning Mr Lee Kuan Yew.” And at that point, Lee Kuan Yew, who was sitting in front, stood up, went to the podium like this, physically pushed the chairman away, and said, “I’m taking charge.” You can imagine this, right? What an electric impact that had.

I happened to be the managing editor of the student newspaper, Singapore Undergrad. So I decided to write a column saying, “We fully understand why Mr Lee Kuan Yew was exasperated—I would have been exasperated too—but nonetheless, there are certain rules of decorum. Mr Lee Kuan Yew shouldn’t push the chairman away. This is a slippery slope to dictatorship in Singapore.” I gave the editorial to my fellow editors. They were much smarter than me. They said, “Kishore, this editorial is so brilliant. Why don’t you put it in your name?” They didn’t want collective responsibility, so I put it in my name.

Frankly, that editorial was the first time I became world-famous, because I was then interviewed by the BBC, the New York Times, and others, all because of one editorial saying that Lee Kuan Yew was going down the slippery slope of dictatorship in Singapore.

But that was, in a sense, part of the growing -p process I had. And I think those four years of constant challenging became a lifelong habit that has stayed with me even now after so many decades. And that’s why the chapter of dissent was very important. And from dissent, I went to diplomacy. And in case you’re wondering how I got in the diplomacy, when you get a President’s Scholarship from the government of Singapore, you are bonded for five years. You have to work for the Singapore Government for five years. And they allocated me to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs accidentally. And I discovered that I enjoyed diplomacy a great deal. I intended to spend only one or two years in diplomacy and then go back to studying and teaching philosophy. But I discovered that being in diplomacy was more enjoyable. And of course, 33 years, I can’t summarise very briefly, but I will just describe a couple of important elements, maybe three elements.

My first posting was quite a remarkable one. When I was 25 years old, I was made chargé d’affaires at the Singapore Embassy in Phnom Penh. You’re wondering why, in my first posting, I became chargé d’affaires. The reason was that the city was being shelled every day.

So they asked a 40-year-old Singaporean diplomat. He said, “I’m married, I have children; I cannot go to Phnom Penh. Very dangerous.” They asked a 35-year-old diplomat, who said, “I’m married, I have children; I cannot go to Phnom Penh. Very dangerous.” Then they asked a 30-year-old who said, “I just got married; I can’t leave my wife and go to Phnom Penh.” And they asked me, a 25-year-old, and I was still living in a one-room house with five people.

So then I went straight to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and I was staying by myself in a five-room house. I had a housekeeper, a gardener, a security guard, a Mercedes-Benz, a driver, and crates of champagne being flown from Singapore to my house every week.

You know, can you imagine? You go from living in a one-room house to living in a five-room house with champagne every week. So it was quite an amazing transformation. But of course, I discovered that diplomacy has all kinds of rituals. The first ritual I found very difficult was when I was invited to the house of the German chargé d’affaires. When I went for dinner, I was very surprised to see so many forks and spoons. I had only eaten with my hands. So I tried to figure out: what do I do with the fork? What do I do with the knife? I watched everybody—I think you take from the outside and you work your way in. So all the basics of diplomacy I knew nothing, but I learned literally from scratch. Again, it was a great learning journey.

And I can tell you, being in Phnom Penh was actually very important. Because if you live in a city that’s shelled every day, once I saw a marketplace that had just been bombed, and I was there five minutes later after the bombing. I walked into the marketplace; artillery shells had fallen about 200 yards from my house. When artillery shells hit cement, the shrapnel goes horizontally and kills many more people. So I saw all kinds of bodies that had been destroyed by artillery with my own eyes. You can study the horrors of war all you want, but when you see with your own eyes dead bodies as a result of shelling, you realise how bad war is—which I think is a very important lesson you need to learn in diplomacy.

The second important aspect of diplomacy is that I didn’t realise it then, but now looking back, when I ask myself how was I able to publish ten books in my life? I think I didn’t know this, but I happen to be sitting at the feet of three geopolitical geniuses in the course of my work. And these three geopolitical geniuses were Mr Lee Kuan Yew—frankly, an amazing guy; Dr Goh Keng Swee—very few people have heard of him; he’s the architect of Singapore’s economic miracle; and Mr S. Rajaratnam, who was the foreign minister of Singapore. All three had remarkable minds. And I used to have hours and hours of conversations with all three of them. When you have hours and hours of conversation with great minds, the learning process is amazing. It was a great privilege in my life to have sat at the feet of three geopolitical geniuses. And I think that if I hadn’t worked with these three, I would never have been able to write the ten books that I eventually ended up writing.

And then, of course, also I became Ambassador to the UN, and as I say in my book, in my two years in the UN Security Council—2001, 2002—was the best education I had on international relations, because before I went to the Security Council, I still had some illusions that principles mattered, international law mattered. After two years in the Security Council, I realise that whenever there’s a clash within power and principle, power always wins, principles lose. That’s the reality, very painful reality. But you don’t realise it until you see it with your own eyes. And that’s what I saw for two years in the UN Security Council. And that’s why I also wrote a book, you know, on the global governance and the UN Security Council. And then when my diplomatic career was ending, you’ll see in my memoir, I describe how depressed I became cuz I wasn’t sure what to do after having served on the UN Security Council, after having been the head of the Foreign Ministry. So, by sheer miracle, I was made the Founding Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. And of course, I had always had a love for academia. I could have ended up teaching philosophy.

I got a job— and a dream job— to become the dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. In case you’re wondering why I got the job, I can tell you it is because nobody wanted it. In the year 2004, even though Mr Lee Kuan Yew had stepped down, he was still very powerful and very influential, and this was the first institution ever named after Lee Kuan Yew that was set up. And all the Singaporeans know: if you take over that institution, you fail, you’re finished. So nobody wanted to touch that job. And I was stupid. I said, Sure, I’ll do it. And again, it turned out to be a great blessing because, you know, it’s such an honour to be given—the Lee Kuan Yew School didn’t exist. The Lee Kuan Yew School was literally created on 16 August 2004, on the day when I became Dean. So literally from birth, I was the founding dean, and there was nothing there, basically, right? Starting from zero.

But starting from zero, within 13 years, the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy became the third best endowed school of public policy in the entire world after Harvard and Princeton. Amazing, right? Starting from zero, nothing. We ended up with a 500 million dollar endowment. And again, in my book, I describe how we went about raising money. And luckily for me, I went to see the richest man in Asia, Mr Li Ka-shing, with a letter from Mr Lee Kuan Yew. And that’s how I managed to get $100 million from him.

And I can tell you in the book, I was advised by everybody that when you go to see Mr Li Ka-shing, don’t ask for too much. You know, if you ask for too much, he will reject what you’re doing. They said, Oh, ask for 20 million, 30 million. Fortunately for me, I decided to ignore the instructions, and I asked for a hundred million dollars. And, to my absolute astonishment, within three minutes, Mr Li Ka-shing said, “Okay, I’ll give you a hundred million.” And then I almost fainted. Cuz that was my opening offer. I thought he would have to negotiate. So I said I was ready to negotiate to see whether he would give less, but he accepted right away. And because he gave one hundred million dollars, we got a matching grant of one hundred million dollars; it became two hundred million dollars. So, by ignoring instructions which told me to ask only for 20 or 30 million dollars, I managed to get two hundred million dollars for the Lee Kuan Yew School. These are the sort of things that I managed to do.

So, as you can see, I also have a reckless streak in me. I would take risks when others wouldn’t take risks in many areas, and I have discovered that risk-taking paid off. So it ended up with me having a very successful stint. And I want to emphasise that the academic standing of the school also went up; it wasn’t just about its financial strength. We were the first public policy school in Asia to be admitted to the Global Public Policy Network—you know, which was set up by Columbia, LSE, and Sciences Po. So we raised ourselves financially, and we raised ourselves academically.

But of course, all good things had to come to an end, so finally I stepped down in December 2017. Then I was no longer employed. I no longer had a responsibility to manage anything for the first time in my life in almost 40 years. Then I had to decide what to do. Technically, I retired on 31 December 2017. But what I’ve discovered is that the last eight years since I retired—the reason I call it Discovery—have ended up being the busiest years of my life. And I’m not exaggerating. It’s been remarkable.

I’ve managed to produce three books in these eight years. And Henry was alluding to it: each one of them became remarkably successful. I mean, I can tell you, for example, Has China Won?, which Shirley ran here, by the way, translated into Chinese here. A round of applause for Shirley for translating it. Most books, you’re lucky if you sell, you know, 5,000; 10,000 is a very good number. That book in English sold 40,000 copies. And again, it travelled around the world quite amazingly and was translated into several languages. Then, after that, there was an accidental book that came about because Henry Wang here called me one day and said, “Kishore, I’m publishing a series of essays with Springer Nature. Give me your essays; I’ll publish them in a book.”

And I remember telling myself, Oh my God, why? What is this for? Who’s going to read this book? So one Saturday morning, I sat in my study and wrote a foreword for the book. In the foreword for the book, I told myself nobody’s going to read it, so I can say whatever I want to say. So I wrote this incredibly strong, outrageous introduction. And amazingly, after the book was released, I spoke to the publisher, Stefan from Springer. I said, What is your target? How many downloads should we get? He said, If you get 20,000 downloads, it is very good. But instead of 20,000 downloads, as Henry said, that meant 4.21 million downloads. The target was 20,000, and it reached 160 countries. You know, it’s amazing. Life is strange—you know, a book that I thought nobody would read. And because I wrote this very angry and direct introduction, boom, it just took off.

So after that, I came up with this book, now that we’re discussing today, Living the Asian Century. And again, I must say so far, it has been very well received. It was for 20 weeks the bestseller in the Singapore Straits Times, which is very long, by the way, for Singapore Straits Times bestselling books. And it tries to describe the story of my life. And to me, what is most heartening is that all the people who actually have read it have said to me how much they enjoyed it.

I will give you an example. One of the most famous novelists in the world is Amitav Ghosh; he’s written incredible novels. And he’s an award-winning novelist, by the way. He said to me that he picked up the book and read it all, almost in one sitting. That’s the biggest compliment he can give to a writer—from a novelist saying, “I read your book in almost one sitting.” So it was gripping enough for people to read it and enjoy it.

So that’s why I’m very glad that the World Affairs Press has decided to publish it here in Chinese. And I hope that it will also be read widely in China. And hopefully, some of the lessons of my life, which I have tried to share in this book, will also prove useful to everyone else. Thank you very much.

Dialogue

Henry Huiyao Wang

Great. So, Kishore, this is really a marvellous and fascinating book that you just described and discussed with all of us—shared with all of us. I’m sure it resonates with many people sitting here. What I actually want to start with is that I’m very impressed with the book. I read it through this translation process, and I found that you had a very harsh early life—you just described a bit of that.

I also remember you saying you were in Halifax in Canada, while you were doing your master’s, there, also a very hard life and poor living conditions. Because I studied in Canada, I know how cold it can be in the winter, right? And also, of course, yes—that’s right—your landlord didn’t provide good enough heating for that.

And then, of course, you had so many diplomatic careers and have now become the VOA—Voice for Asia. So I would like to hear what drives you—what’s your mission, and what is really the key success factor? I mean, if you look at it not from rags to riches, but from a poor boy through academia and the think tank community to a global thought leader, what have been the key factors that drove you to realise this great career and the establishment that you have? Maybe this is a question I didn’t check with you before, Kishore, but I’d like to ask you.

Kishore Mahbubani

Thank you. Actually, that’s a very difficult question to answer. You know, I would say it’s a variety of factors. Clearly, my peers would describe me as someone who’s very ambitious. Where that ambition came from, I don’t know. But I think it was also basically that I happened to work with people who inspired me, you know. And that’s why in my book, I spend a lot of time talking about Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee, and Rajaratnam. Because I realised that when I worked with them, they set very, very high standards. They had a very, I would say, important rule—which I would call, in simple terms, the “zero bullshit” rule. The minute they smelled any bullshit, you just got killed by them. Absolutely killed by them. They didn’t want any kind of rubbish. So when you wrote something for Lee Kuan Yew or Dr Goh, you had to set very high standards in meeting what they asked you to do. So those high standards then became a kind of lifelong habit.

For example, I noticed that whenever Lee Kuan Yew spoke publicly, he never wasted a word. He always made sure that every word he used had some meaning and some consequence. And he spoke very sparingly and didn’t try to use very high-flown English, but just used very simple, short, clear, direct sentences, very simple, clear, direct messages. And so in a sense, I basically began emulating them. And then I found that by the result of emulating them, people would start listening to me.

But the other big change in my life that happened is that I happened to be at Harvard at the end of the Cold War in 1991–1992. I spent a year there as a fellow of the Weatherhead Centre for International Affairs. At that time, there was incredible triumphalism in the West, you know. They were so happy that they had defeated the Soviet Union, and they believed, as you know, they had reached the “end of history,” that the rest of the world had to become carbon copies of the West, to quote Francis Fukuyama. So at a Harvard seminar, I said to a very distinguished Harvard professor, Stanley Hoffmann, who was a very wonderful human being, by the way—he was talking about how the future was going to be Western. That was the first time I stood up and said to him, “I’m sorry to disagree with you, but I think the future is in Asia, not in the West.”

And I was amazed. He actually lost his temper. His face went red; you know, he became almost apoplectic when I said that. So that’s when I first encountered the resistance in the West to any suggestion that Asia was rising. But what’s interesting is that I’ve now been writing about the rise of Asia. My first essay was published in The National Interest magazine in 1992, right? That’s 32 years ago. So I’ve been predicting the rise of Asia for 32 years. Unfortunately for me, Asia keeps rising.

And all the predictions I’ve been making have been coming true. So there is a kind of virtuous cycle now. Several people—in fact, in the United States, the honest ones—have come to me and said, “Kishore, we should have listened to you 20 years ago when you told us that the world is changing and that Asia is returning.” And that’s also why I think this book, The Asian 21st Century, which you published, has been so successful—because it really captures the mood of the world. So, in a sense, if I have been successful, I’ve also been riding a tidal wave, and that tidal wave is the return of Asia. And that’s what all my writings have been about, and that’s what everybody is paying attention to.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Great. I think I can summarise that your success is also attributable to great ambition and high standards—you have mentors, and you pursue excellence, following high-standard examples—but also to the courage to challenge, which you’ve done very well.

Now, you talk about The Asian 21st Century, the book we did together. What do you think about Asia now? For example, we see ASEAN as such a miraculous success story. I remember probably 10 years ago, you and I published your ASEAN Miracle as well, at a launching event at Peking University. So, what do you think of the current moment, with ASEAN expanding, becoming 11 members now, and with the APEC summit just finished? What is the future, compared with the other continents? What are the reasons you think Asia is rising and developing, becoming, probably, the most important geopolitical arena in the future?

Kishore Mahbubani

Well, I’m glad you mentioned ASEAN, Henry. I can say that I’ve been talking for a long time about the rise of the CIA countries. CIA doesn’t stand for Central Intelligence Agency; CIA stands for China, India, and ASEAN. And if you want to understand how amazing the growth has been, let me just give you three statistics to illustrate this.

Take China. In the year 2000, when the 21st century began, the combined GNP of the European Union was eight times bigger than China’s—eight times bigger in the year 2000. Now the European Union and China are the same size. By 2050, the European Union will be half the size of China. So, can you imagine? In 50 years, the European Union is going to go from being eight times bigger to becoming half the size of China—that’s a structural shift that rarely happens in history. This is an amazing structural shift.

Now, if you take India. India, as you know, was colonised by the British, so it’s good to compare it with the UK. In the year 2000, the British economy was almost four times bigger than India’s. But today, the Indian economy is bigger than the British economy. And by 2050, India’s economy will be four times bigger than the UK’s. So, as the 21st century opened, the UK was four times bigger than India; by the middle of the century, India is four times bigger than the UK. Again, a shift.

Now, let’s take ASEAN, and I compare ASEAN with Japan. Japan was the world’s second-largest economy in the year 2000—huge, second-largest economy in the world. Again, in the year 2000, Japan was eight times bigger than ASEAN. Now, Japan is only 1.2–1.3 times bigger than ASEAN. By 2030, ASEAN is bigger than Japan. And remember the book, Japan as Number One that was created.

So what we’re seeing—what we’re witnessing in our lifetime—is structural shifts of a magnitude that rarely happens in phases of history. I mean, basically, if you want to compare this period, you have to compare it to the Industrial Revolution, when Europe just took off, you know? And subsequently, Europe was able to dominate the world, and economies grew dramatically. But the economic growth of the Asian countries has now been stunning. And I expect, given all the forecasts I’ve made, that the Asian countries may even do better than what I have forecast for them, because there’s a virtuous cycle.

And in the case of China, for example, I mean, again, when future historians look at our time, they will look at the structural shifts that are happening. Take, for example, China: in the year 2000, when the 21st century opened—I like to start with 2000 because that’s when the 21st century opens—China’s share of global manufacturing was only 5%, but by 2030, China’s share of global manufacturing is going to become 45%. How do you go from 5% to 45% in 30 years? That requires incredible ingenuity, discipline, planning, hard work, dedication—a remarkable series of attributes before you can achieve what you have achieved.

And, as you saw recently at the meeting between the United States and China, again, for the first 25 years, it was only the United States that could put pressure on China, and China couldn’t put pressure on the United States. But as you saw, and as President Trump has now acknowledged, the world has become a G2 world. Right?

China today can also exercise some leverage over the United States as it did with the use of rare earth. So, by the way, these are all profound structural shifts in our international order that I think future historians will be amazed by. So what I hope with my writings is to provide glimpses to future historians of how and why our world is changing so dramatically and why is Asia doing so well.

Henry Huiyao Wang

So you mentioned Asia—all the statistics are taking off and things are happening. Do you have a sense of the key attributes behind this? What exactly is driving it?

I remember when the former U.S. ambassador, Terry Branstad, was leaving China, he held a reception. I was there, and he said the three things that impressed him most about China were, first, family values and strong family ties; second, the enormous importance attached to education; and third, hard work. Do you think there is an “Asian values” factor that could continue to propel Asia’s development in the future?

Could Asia come together more, given the examples we already have in China, Japan, South Korea, and possibly India, and of course, ASEAN? Do you envision an Asian common market or an Asian Union someday, perhaps repeating ASEAN’s success?

Kishore Mahbubani

Well, you know, as I mentioned earlier, that the one lesson I learned from Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee, and Rajaratnam is that we must be ruthlessly honest in our analysis. So when you ask why Asia is doing well, the first honest answer we have to give is that we Asians were the first to learn from the West how to succeed.

So, as you know, in my book The New Asian Hemisphere, I describe how the Asian countries succeeded by studying, understanding, absorbing, and then implementing the seven pillars of Western wisdom. For example, the mastery of modern science and technology, we in Asia learned from the West.

You look at free-market economics, which, you know, explains, for example, China’s spectacular success. We learned it from the West. So we should acknowledge the fact that we have learned lessons from the West.

But at the same time, one reason why the Asian countries are also doing so well is that at a time when Asia was rising, many countries in the West decided to go to sleep. And that’s why I say, in a very cruel fashion, that Francis Fukuyama’s essay The End of History did a lot of brain damage to the West—because he put the West to sleep in 1990 at precisely the time when China, India, and the rest of Asia were waking up. So, I mean, that was an amazing coincidence in timing. And the West should have realised that the past 200 years of Western domination of world history were a complete aberration.

And so when you say why are China and India and ASEAN, and all doing well? The simple answer is that they are great civilisations in Asia, and they have always been great civilisations in Asia. But unfortunately, they went to sleep at a time when the West was waking up. And that’s why in the year 1950, even though China and India combined had about 40–50% of the world’s population, they only had 5% of the world’s GNP. And the United States in 1950 had 50% of the world’s GNP.

Now that was an aberration. So what you’re seeing, therefore, is the end of the aberration and a return to the normal. And the one advantage that Asians have is that, because of their old civilisations, they have a much higher degree of cultural self-confidence. And that cultural self-confidence is an asset for Asian countries, and that, I suppose, reflects your point about the Asian values. But again, remember that many of the Asian countries lost their self-confidence.

Now, many of you may know my first book was called Can Asians Think?. And in that essay, I quote someone. I actually quote a Korean who was asked in the 1950s, you know, “What do you Koreans think about this?” And this Korean said, “I don’t know whether we can think.” That was the amazing damage that was done by Western domination of world history.

So right now, I mean, frankly, if you look back over the past 3–4,000 years of human history, I’m shocked that most people don’t realise that we are now living through one of the most exciting periods ever in terms of scale and pace of change. And the good news for me is that I’ve been trying very hard to capture these large changes that are happening. And many people can feel that these changes are happening, but they’re trying to find the ways and means of describing these changes. And that’s what I try to do in my writings.

Henry Huiyao Wang

That’s great. I personally think, of course, there are Asian cultural heritage, traditions, and values, as you mentioned. But this has also been compounded by the globalisation movement. China’s opening up in 1979 was an embrace of globalisation, and then its joining the WTO further opened global exchanges. All of that made the success of Asia as well.

Now, before I go to our distinguished guests here for further Q&A, I want to ask a final question about the China–U.S. presidential summit just concluded last week. I think that summit has put China and the U.S. on an equal footing. For the last eight years, the U.S. has gotten used to sanctioning China, and China was on the receiving end; now China has started to push back, and the U.S. probably, for the first time, also recognises this. But this is really counterproductive.

So I think in the second term of Trump, he has probably adopted a more pragmatic approach: he doesn’t want to escalate a conflict with China, and he is really engaging in dialogue. For example, I was amazed by the five rounds of talks between Scott Bessent, Vice Premier He Lifeng, and China’s chief negotiator Li Chengang. Five rounds of talks set a great framework. And then they actually reached a successful conclusion in Busan, South Korea, last month. As President Trump put it, on a scale of one to ten, “I give it a twelve” for this success.

And of course, as you said, he mentioned this G2 thing, but also President Xi mentioned that we should get rid of this vicious cycle of retaliating against each other, and that “Make America Great Again” and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation—these two objectives—do not conflict. So they can be more responsible for other big affairs in the world. You know, they talked a lot about the Ukraine war and how they can probably work together.

So do you think that in the second term of Trump—because China in the last eight years, through the trade wars, was never really contained; actually, it reached record exports and imports, and also developed the “DeepSeek moment” and the Victory Parade last month or two months ago—do you think that now the U.S. finally recognizes China as an equal, and that we can probably get to some kind of new normal? The two countries are big enough that we cannot really afford a war, because if we have a war, that would be MAD—you know, mutually assured destruction.

So, if that is the case, can we have a kind of Olympic-style peaceful competition? Because even if we go to sanction each other, it’s going to hurt both countries and hurt the rest of the world. So we need to enter a new, fair paradigm.

Kishore Mahbubani

We share your vision and hope that U.S.–China relations have finally stabilised, and that both sides will now engage in competition but within guardrails, and everything will be more or less steady from now on. But unfortunately, since I was a student of three geopolitical realists, I predict that this stability will not last, because it is abnormal. The normal situation is what we have experienced over the past 2,000 years: the No. 1 power will never gracefully allow the No. 2 power to overtake No. 1 power and say, “Okay, your turn has come. Please take my seat. I’ll become No. 2.” And, as you know, in the United States, it is politically suicidal for any American politician to say, “Let’s prepare for the day when we become No. 2.”

The only man brave enough to say this, by the way, was former President Bill Clinton. In a speech at Yale in 2003—and I discuss this speech in my book The Great Convergence—he said: if America is going to be No. 1 forever, we have the “juice” and we can keep on doing what we’re doing. Then he added a “but.” He said, but if we can conceive of a world where the United States is no longer No. 1, then surely it is in America’s interest to strengthen multilateral rules, multilateral norms, multilateral processes, and multilateral institutions.

But he gave that speech only once and never repeated it. And I can tell you this: in my book The Great Convergence, I quote his deputy secretary of state, Strobe Talbott, saying that several times when he was President, Bill Clinton wanted to give speeches preparing the American people, saying, “Hey, we cannot be No. 1 forever. So let’s think about a world where we become No. 2” And all his advisers said, “You will be killed politically.” That’s why even Joe Biden once said publicly, “China wants to become No. 1,” and Joe Biden said, “It ain’t gonna happen on my watch,” which means that no American president can allow the possibility of China succeeding.

And so, over the next 10 years, China’s growth will continue. China’s GNP in PPP terms is already bigger than the United States. China’s GNP in nominal terms will get closer and closer and closer to the United States. And the closer and closer it gets, the more insecure, clearly, the United States is going to become, and the pressures to stop China will increase in one form or another. So, sadly, I’m very happy that the outcome of the meeting between President Trump and President Xi was so positive; it exceeded my expectations—but never believe that when you have these calm periods, that is the end of the contest. The contest will last for another 10–20 years.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Yeah, but I just want to add that I think, as I said, in the second term of Trump, China and the U.S. have reached some kind of equilibrium—on an equal footing. And if that is the case, on the military front, we cannot fight each other; it would be mutually assured destruction. We can’t afford it. On the economic front, I think the U.S. will gradually realise we also cannot fight like that because it also hurts us and hurts China, since we are so intertwined—not only semiconductors, rare earths, pharmaceuticals, shipbuilding, and everything. So it has to compete through other means, not necessarily military, because on the military front, a strategic deterrent has already been established. But if it’s only doing all kinds of economic competition, China is resilient enough.

So I think, as Secretary Rubio rightly said in July when he was interviewed on Fox News, China and the U.S. are going to reach a new strategic stability. This new strategic stability, I think, could probably last during the next year or two of Trump’s term—three years—with two visits happening: Trump coming to China, President Xi going to the U.S., and then he has another two terms. So, probably, if we can reach this next moment—having this strategic stability established—that is probably a historic turning point of the summit we had in Busan, South Korea. Now I’d like to open the floor to our distinguished guest, the Ambassador from Pakistan, please.

Khalil Hashmi, Ambassador of Pakistan to China

Thank you very much. Thank you, Dr Henry. Thank you, Ambassador Kishore Mahbubani; it’s always a delight to listen to you. You certainly have a gift of gab and excellent storytelling. You gave us a very riveting account of your book and generally painted an exciting picture on the larger development front—what is happening or what is going to happen in the next 10 years.

I wanted to take you to another, rather less promising and more worrying scenario that is also developing on the larger geopolitical or security front. Because, as someone who has worked with three geopolitical realists, I want to take you back to 2001. You used 2000; I would take you back probably to 2001. That was the time when the hinges that stitched the world order—the normative hinges, international law, and the international institutions that glued the international system together—started coming off. You know what happened: 9/11, the tragedy that happened, and the response that came from the United States and other countries. After that, what started happening to the World Trade Organisation and other institutions?

So we have seen a consistent trend of erosion of international law norms and all that stuff, which was put together to save the succeeding generations from the scourge of war. But here we are in 2025, so we have seen these things deteriorate. So the most powerful states are clearly exercising the choice not to play by the rules that they once decided for their enlightened reasons to do that.

Now, if you look at this region, which is thriving, but there are also worrying clouds—if you see elements of a China containment strategy, the Quad, and other things. So do you think, as someone who has seen these things up close, and also on the nuclear front and other aspects, with the United States announcing, okay, maybe we might be resuming nuclear testing, so the era of arms control is also over.

What worked before was either the normative deterrence or some form of arms control mechanisms existing. With these things gone, how do you paint the next 10 or 20 years, alongside what is happening on the economic front, which is a promising picture? We have to mesh these because we are living in a world where we’re seeing worrying developments on the security situation, especially in the Asia-Pacific. We know what is happening in Europe, for example. What is your assessment? How would you see it in 5, 10, 15, and 20 years from now?

Kishore Mahbubani

Yeah, I must say that’s an excellent question, because you point to one of the biggest challenges of our time, which is the challenge to the normative order and what people in the West call the post-1945 rules-based order. And you’re also right in terms of: I like to think of 2001 as a critical year of change. And, actually, it was Singapore’s good fortune that we were members of the UN Security Council in the years 2001 and 2002. Because even though we were members for two years of the same Security Council, actually we were members of two completely different UN Security Councils.

There was a UN Security Council pre-9/11, which was basically sleeping, doing nothing, and nobody cared. Nobody was interested. And I was in New York, Manhattan, when 9/11 happened. I saw the traumatic effect it had on the United States. I saw how it woke up the United States. The United States actually didn’t have an ambassador to the UN until 9/11 happened. And then they immediately appointed an ambassador to the UN.

And then, immediately, the Security Council became the battleground for one of the fiercest battles ever about whether or not the United States could legally invade Iraq. And I was in the Security Council watching the debates at first hand, sitting next to Sergey Lavrov, who was my neighbour when you’re on the Security Council. So there were two different Security Councils. And there’s no question that the global normative order has been challenged since 2001. You’re absolutely right.

But what is to me amazing is that even though it’s under severe challenge, it hasn’t broken down. In the past, normally, whenever the United States took the lead, many countries would follow—saying, the United States takes the lead, it must be the right thing; we must follow the United States. But what’s interesting is that this time around, since April Liberation Day, after the United States raised its tariffs on the rest of the world, normally you would expect some countries to follow the United States and raise tariffs on the world. Not one other country has done so. Not one. So it’s amazing: the 192 other countries in the world are saying, “We’re sticking to the WTO rules. We’re not leaving them at all.”

And indeed, other countries are actually deepening their economic liberalisation with each other. For example, Indonesia—which in the past used to be conservative about free trade agreements—after the April Liberation Day managed to complete a free trade agreement with the European Union, which it had been negotiating for 10–15 years. The fact that most countries in the world are sticking to the normative order is, I think, one of the most positive things that is happening in the world.

But on top of that, I must say that the decision by President Xi to launch his Global Governance Initiative could not be better timed, because you find that around the world, the demand for global governance is growing. Most countries in the world want greater stability in the international order, in the global order, so they can grow their economies. They need stability to grow their economies. But at a time when the demand for global governance is growing, the supply of global governance is going down. And so the fact that China has decided to take the initiative to launch this initiative shows that many countries, including China, understand that we must protect these global governance institutions.

So, at a time when we should be pessimistic for the normative order you’re talking about, I’m actually not completely pessimistic. I see lots of signs that indeed, the rest of the world will come around to protect many of these institutions, including, for example, the World Trade Organisation.

Jesús Seade, Ambassador of Mexico to China

As a keen observer of many of the historical developments you mentioned, I was very happy to be a negotiator for my country in the creation of the WTO and the founding deputy head of the WTO. And I was also in Washington, DC—well, not “also”; you were in New York—on that fateful 9/11. My secretary came and said, “Mr Seade, a plane has hit one of the Twin Towers.” I said, “What?” and I kept working. I was working early that day; 20 minutes later, the tower collapsed—“What?”—and I kept at work, and then 20 minutes later, the second tower, and the world changed.

I fully agree with the sense of scepticism we have expressed on an easy reading of recent and current developments—where are they going? The world is not following the United States; at the same time, in the United States, there is a consensus that people are quite wrong to think that President Trump is thinking in a certain way alone; there’s a consensus about certain things. President Clinton said what you said 22 years ago. But in general, I think not many people are ready to accept the fundamental changes that are going on.

I remember a fantastic saying—an expression by one of my favourite philosophers, the baseball player Yogi Berra, who said, “It’s very difficult to make predictions, particularly about the future.” So I prefer not to try to speculate about current developments—where they’re going—and to go for the real future, to look at underlying trends, and ask you how you see that hitting the main balances on the economic front and on the security front for the world.

And the main trend that I see happening that has not received a lot of attention or commentary is the fact that China continues to have a gigantic trade surplus with almost every major region in the world. That means an amazing amount of currency—U.S. dollars—is going to China. But China is not going to pile it up; it’s not doing that. It goes back out in the shape of investment—it has to.

So the trend that I want to talk about is one where the big trade imbalances that have been hitting the world over the last decades—50 years, which are denounced by Americans, Europeans, and many countries around the world: us taking employment from them, and so on, because the jobs and production are in China. Well, that’s no longer happening that dramatically. The underlying change that I see is that those dollars are returned to the rest of the world in the shape of Chinese investment around the world. So I see some of these imbalances being mitigated on employment.

But in exchange, I see greater and greater participation—if we want to be positive, we’re going to say partnership, and that’s great—and ownership of Chinese capital and Asian capital around the world. You can make a positive, gentle reading of that. You can imagine alternative, different, troublesome stories around that. I want to ask you: how do you see this trend? Making it cartoon-like, simplistic, we reduce trade imbalances, but we increase, phenomenally, Chinese and Asian investment around the world. How would that affect global politics and global security balances? Thank you.

Kishore Mahbubani

You’re absolutely right that China is generating massive trade surpluses. I mean, this is an undeniable fact, you know? And clearly, there’s no question that some of these large trade surpluses are also generating political problems for China, fairly. And you can see this is what many Americans complain about, you know, in terms of the large trade deficits that the United States has. But, you know, at the same time, you must also be very intellectually honest and acknowledge that the United States also has large surpluses in services that nobody mentions.

They actually are helping the United States quite significantly. There’s a reason why the United States is still the richest country in the world, okay? A lot of dollars are going to the United States also; they’re not going to China only, right? And if President Trump succeeds in getting all countries like Japan, South Korea to invest massively in the United States, dollars are going to the United States, too.

So it is a complicated picture, not a one-sided picture. But I do think China has got to pay attention to the fact that its large trade surpluses are creating a political backlash. And therefore, it’s got to find ways and means of rebalancing its trade with many countries, and there are many ways of doing so. And one way is the one you suggest, which is for China to start investing in other countries.

I must say again, I give the Chinese government credit for having launched the Belt and Road Initiative at a timely moment, because the Belt and Road Initiative is a way of providing long-term capital to developing countries to develop infrastructure that no private sector would ever develop. So that’s how you have this remarkable situation today, whereby Laos, as you know, is one of the poorest countries in the world, literally. Yet even though the United States dropped more bombs on Laos than it dropped in Europe in World War II, today, Laos has a faster train than the United States because of the Belt and Road Initiative. It is quite remarkable. And then if you go to Jakarta–Bandung, there is a train called Whoosh. Again, Indonesia today has a faster train than the United States does, again as a result of the Belt and Road Initiative.

So I think if China enhances the Belt and Road Initiative and finds ways and means of, you know, investing more in developing countries, that will help to remedy some of the political backlash against these trade surpluses. But I must also emphasise that, you know, Singapore doesn’t believe that trade deficits are bad. In fact, we don’t have a trade surplus with the U.S.; we have a trade deficit with the U.S. But that’s not bad. It’s okay. It means that we are buying more competitive products from the United States of America. We buy very good planes—Boeing planes—from America. So that’s the reason why we have a trade deficit with the United States. So you must get rid of this idea that trade deficits are bad and trade surpluses are good. I mean, overall, you must have a reasonable balance. But when you suffer a trade deficit with one country and a trade surplus with other countries, it is perfectly normal. So you must look at the comprehensive picture and not just at your bilateral trade deficits.

And I can tell you one thing. To me, what really makes me happy is that the countries of East Asia now have the cultural confidence to continue with free trade arrangements. For example, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which is the world’s largest free-trade agreement, including China. It also includes four of America’s allies: Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, and the 10 ASEAN countries, and it is functioning very well, right? We’re not interested in our bilateral deficits or surpluses; it doesn’t matter. What matters is the overall economic growth and well-being of our countries, and ASEAN, as you can see, is growing steadily. So we look at the overall picture, not just a particular slice of bilateral trade deficits or bilateral trade surpluses.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Maybe I could add that, you know, I think China has entered this stage of massive investment happening. You see, I was just coming back from Brazil—BYD opened a big factory there, and President Lula was at the opening. I also just came back from Turkey—BYD invested in another big factory in Turkey as well. So you need a really good political climate, like when China invests heavily in Hungary, in Serbia, in Spain, because we have good relations. In order to have good relations, I think they will be assured of big investment coming out of China.

Also, the trade war has actually pushed Chinese companies to invest to avoid tariffs. So they can be “in the world, for the world”—it used to be “in China for China,” or “in China for the world.” Now, Chinese companies are going to be “in the world for the world,” manufacturing everywhere. That will probably make supply chains more resilient. So, like what the Japanese did in the ’80s and ’90s with their massive investments, quickly solving those trade disputes and stabilising the situation. Maybe we have a last question from this international organisation representative.

Changhee Lee, Director of the Country Office for China and Mongolia, International Labour Organisation (ILO)

Thank you so much, Ambassador Mahbubani. Nice to meet you after the BRI meeting in Harbin two years ago. Always your stories are inspiring. One question: we’re talking—I mean, your Living the Asian Century is very clear when it comes to the economy. Asian economies are thriving, prosperous. But when it comes to the cultural dimension or political dimension, do you have an Asian identity? How would you define your Asian identity? I mean, we have connections in terms of culture and civilisation.

Kishore Mahbubani

Yeah, very good question. And in fact, I remember there was a column written by Martin Wolf once in the Financial Times that said there’s no such thing as Asia. There’s Chinese, there’s Indian, there’s Malay, and so on and so forth, right? But I think what is missing in that analysis is an understanding of what the reality of Asia was like before the Western colonisation of the world happened. Before the era of Western colonisation, there were organic links all over Asia that were cut off by Western colonial rule. And to give you an illustration, I tell a personal story to show illustrate different parts of Asia are connected.

Now, I am ethnically Sindhi—Sindh is, as you know, now part of Pakistan—but I grew up as a Hindu Sindhi. And as a Hindu Sindhi, obviously, I had connections with the Hindus in India, right? One billion of them. But, amazingly, the one part of the world that was most affected by Indian colonisation or Indian cultural exports was Southeast Asia. So nine out of the ten Southeast Asian countries have an Indic base. And you know what is shocking is that when the president of the world’s largest Islamic country, Suharto, wanted to celebrate a moment in Indonesia’s history—and he’s Muslim—he decided to build one of the largest statues of Arjuna from the Mahabharata right in the middle of Jakarta. So the leader of the world’s largest Muslim country built a statue from the Mahabharata. That shows you the impact of Indic influence in Southeast Asia.

But then, when I go to West Asia, people also recognise me. So they look at my name, Mahbubani, which comes from the word mahbub, which means “beloved,” and the Arabic and Persian ambassadors will say, “You’re one of us,” right? And the script I learned to write as a child, even though I’m Hindu, I learned to write the Arabic script, not the Hindi script. So I have a cultural connection with the Islamic world, too. That’s me alone.

And then, when I travel to China, Japan, and Korea, everywhere I go, I visit Buddhist temples. When I was young, my mother would take me to a Hindu temple, my mother would take me to a Buddhist temple. Buddhism came from India. And they said, “It is the same. What’s the difference?” You can pray in Hindu temples, and you can pray in Buddhist temples. So, you know, just my own personal story indicates that there are deeper cultural connections in Asia that were actually suppressed by 200 years of Western colonial rule, and now you see a rebuilding of these connections.

I remember sitting once at an airport in Calcutta, and to my surprise, I met a young Korean lady there. I said, “Where are you going?” She said, “I want to go and see the birthplace of the Buddha in India.” Right? So that’s an example. And, as you know, you have some of the most amazing Buddhist monuments in Pakistan, in Afghanistan, and in other places. So clearly, there were organic links all throughout Asia that had been there for most of the past 2,000 years.

And so, even though the Mexican ambassador said it’s not good to make predictions about the future, unfortunately, so far, most of my predictions have come true. I predict that after the current economic resurgence of Asia, you are going to see a massive cultural renaissance happening in Asia. And when that massive cultural renaissance comes, you’ll see the Asians discovering, oh, 500 years ago we did this together.

And I can tell you another remarkable thing: I remember I was somewhere in South Korea—I forget which city, I forget which museum—and there was a whole show about some Indian princess who came to South Korea five or six hundred years ago. How did this Indian princess end up in South Korea? What was she doing there? I don’t know. But this is an example of the old connections that had been cut off by 200 years of Western colonial rule that is not gonna come back. And that’s why, actually, I want to try and live for the next because the next 25 years are gonna be absolutely fascinating.