Transcript: CCG VIP luncheon on the 15th Five-Year Plan

Scholars from leading universities, including a contributor to the 15th Five-Year Plan, shared insights on industrial upgrading, green transition, consumption pattern, and China’s next planning cycle.

On 31 October, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) hosted its 18th CCG VIP Luncheon themed “The 15th Five-Year Plan and New Opportunities for Global Development.”

The featured speakers were

LIU Baocheng, Associate Professor at the Department of Marketing and Director of the Center for International Business Ethics, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE)

HUANG Yanghua, Professor and Deputy Dean of the School of Applied Economics, Renmin University of China

WANG Zhi, CCG Senior Fellow; Visiting Professor at the Institute for Global Development, Tsinghua University

17 ambassadors—from Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, and Turkey—were in attendance, alongside diplomats from Brazil, Canada, Croatia, Estonia, the European Union, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Malaysia, Malta, the Netherlands, Turkey and Vietnam. Representatives from international organisations, chambers of commerce, multinational corporations, and both Chinese and international media also took part.

CCG has uploaded the video recording of the luncheon to its official YouTube channel and WeChat blog.

The following transcript is based on the video and has not been reviewed by any of the speakers.

Mabel Lu MIAO, Co-Founder and Secretary-General, Center for China and Globalization (CCG)

Your Excellencies, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. It is our great honor to host so many distinguished ambassadors and dear friends today to discuss such an important topic — the outcomes of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and we know that this year marks the beginning of drafting China’s 15th Five-Year Plan, which will lay out a new blueprint for the country’s high-quality development in the coming years.

Today, we’re talking about this hot topic. We know that last week, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) concluded in Beijing, where the leadership mapped out the world’s second-largest economy’s development and priorities over the next five years. The meeting deliberated and adopted the proposal of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on formulating the 15th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development, which established the direction for China’s modernisation process in the next five years and even by 2035. This meeting was far more than a simple stage summary, as it stands as a landmark turning point, forming institutional certainty for China’s response to global uncertainty through a new balanced system that I call high-quality development, self-resilience in science and technology, expanding domestic demand, and coordinating security.

And for seven decades, China’s five-year plans have been a major driver for its progress. Their uniqueness lies in combining strategic vision and measurable targets, creating a roadmap for investment, industry policy, and social priorities. As outlined in the meeting communiqué, China will build a modernised industrial system and reinforce the foundations of the real economy, achieving greater self-resilience and strength in science and technology, while developing new quality productive forces and building a robust domestic market.

Today, we are so privileged to have such a distinguished assembly of minds here. We have invited three distinguished experts on these fronts. Later, we would like to invite them to deliver their speeches, each for about 15 minutes. After their part, we will move to the part that many people are very interested in — the Q&A. We would like to engage everyone and have a very fluent and interesting conversation in English. And first of all, let me introduce our distinguished first speaker.

He is Mr Liu Baocheng. Professor Liu Baocheng is a professor in the Department of Marketing. Professor Liu is very well known both in China and internationally. He is the Director of the Center for International Business Ethics and a professor at the Business School of the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE). He is not only an academic authority but also an active public intellectual, serving as a frequent commentator for major international media outlets like CGTN, where he provides insightful analysis on global business, trade relations, and corporate governance. His research interests span business ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), marketing, and cross-cultural management. With his profound theoretical knowledge and practical insights, Professor Liu has long served as a strategic advisor to numerous multinational corporations and government bodies, making him one of China’s most influential voices in the fields of business ethics and globalisation. Today, I know Professor Liu has prepared a PowerPoint presentation, which will be shown later. We would now like to invite him to share a macro vision on the new Five-Year Plan and the outcomes of the just-concluded Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the CPC. So, the floor is yours, Professor Liu.

LIU Baocheng, Associate Professor at the Department of Marketing and Director of the Center for International Business Ethics, University of International Business and Economics (UIBE)

I’m not that famous compared to your boss, Wang Huiyao. Well, it’s such a pleasure to have been invited by CCG, which is a very outstanding organisation that brings the global community together to share ideas and, more importantly, in a more faithful manner instead of rhetoric. I’m also impressed by so many Excellencies present here. I’ve been talking across the road at CGTN for the last three hours, so please remind me if I exceed another three hours. I think I’m more or less in a position to talk about the next Five-Year Plan because I was one who presided over the critical assessment of the 14th Five-Year Plan and contributed one chapter to the next Five-Year Plan. Hopefully, our Congress will be able to approve it next March.

So here are some of my readings over what is in store for China, and what are the implications for the rest of the world that you guys are really leading.

Very simply, the Five-Year Plan is there to build such a very consistent but plain logic: where we are. Every decision will have to be based on a correct, if not precise, assessment of where we are, what our strengths are, and what are those challenges we face both at home and overseas, when we grow more and more mesmerised with the globalisation drive, which is also under fragmentation. Then, where do we want to go? What are the goals that we really want to achieve? And then, how do we achieve them? What are the paths lying ahead?

So following this logic, I’m gonna share a few slides. The strengths as identified by the new communiqué produced by our Politburo and the plenary session are these: We still have fundamental stability, socially, I think. One thing that you have to agree on, even though you have many different opinions about China, is that China is safe. So with a 1.4 billion population, people are able to behave themselves to create a safe environment. That’s really the foundation for China to move forward and roll out the strategic plans.

Then, the economy is also rather stable. People read that China is now declining from the double-digit growth, but think about it: when you build the second floor, that’s 100% growth. But now, you build the economy on top of the 20th floor, of course, percentage-wise, it’s going to decline. But still, to maintain across the next five years around 5% growth rate is already impressive enough. The prediction by the IMF, just released yesterday, is 4.8%. So between 4.5% and 5.5% is already very reasonable. This will also help ensure that we can fulfil our Centennial Goals by 2049.

The economic advantage is not only in terms of the speed of growth, but also in the integrated industrial clusters we are forming. Through my investigation, if you build a motorcycle plant in the Yangtze River Delta area or in the Pearl River Delta area, within one week, within a radius of 50 miles, you get almost everything. If you do it in some other neighbouring countries, you still need to source from China many parts and expertise. So this is one of our strengths.

Also, when the government is promoting more regional integration, by linking Beijing, Hebei Province, and Tianjin, and also building the Yangtze River Delta integration and the Pearl River Delta integration with Hong Kong and Macao, etc, that’s really something that supports the strong growth of Chinese industrial clusters. We have also moved in stages from special economic zones to high-tech zones, and now to free trade zones. This is a gradual upgrading that we are engaged in. So that’s our advantage and large potential.

China’s savings rate is most recently still 54%. So people have money in their pockets, but how is that going to be unleashed? What is the variety and quality of products? That’s something for the business society to think about. It’s not really about how the government can do it, but how businesses can really bring about value in exchange for the money in Chinese households’ pockets.

Then, in terms of advantages, we are becoming more and more confident about the Chinese socialist construct. Every nation is engaged in two things: growth and distribution. Right now, we see more and more polarisation; even now, disruptive technologies or the fourth industrial revolution create more divides. That’s something I observe. So, how to divide the cake after it’s grown? That is something that China is going to address with this socialist doctrine. So the fact that President Xi has brought millions of people out of extreme poverty. I think that is very laudable.

And then, the abundant talent pool. China produces over a hundred million engineers. They work hard, and more importantly, don’t form unions to bargain with capitalists, so it’s more of a harmonious relationship. There are still 300 million migrant workers who leave their homes and work on assembly lines in coastal areas and in the service sector. This is still a demographic dividend that China can really cash in on. But of course, we are going to provide better social welfare and gradually increase the minimum wage requirements.

The challenge is, of course, that Donald Trump has just departed from Asia after his whirlwind trip, and now I think the dust has almost settled, at least for the next one year. Protectionism is going on, and it’s also driven by stronger nationalism and populism. Still, I have been reading President Xi Jinping’s speech at APEC this morning, it’s time for us to really gather concerted efforts to defend multilateralism and go after minilateralism. The basic notion that the division of labour boosts efficiency, formulates global exchange, and helps achieve shared prosperity, is something that really cannot be severed or ignored.

Domestically, we are also going through an uphill transition because people are more or less path-dependent. If I succeed with low-end manufacturing by extracting more sweat from the workers, why should I change? So, we really need to retool people’s mentality and also create an environment in which people can truly upgrade their technology, improve their management, and expand their vision for the global marketplace. This is not an easy job, but it is very promising.

Something that is not really mentioned in the next Five-Year Plan, which I really wanted to talk about, is the red tape. There is a growing bureaucracy, and there are so many smart graduates from top universities, but they have inadequate touch with real-world realities, and they are very quick in building red tape—different policies, etc. So, I think they need to be educated and also need to be dialogued with about real concerns and realities. They are smart enough.

Then, on consumption, in spite of China’s big push to unleash consumption power, people are still very cautious for two reasons: one is the job security issue; the other is the social welfare network that can really give them a mattress in case they fall, whether because of their job or a family crisis. That’s something that can really help unleash spending.

Demographic imbalance is something quite critical. Now we have nearly 300 million senior people, and that’s both an opportunity and a drag on the economy, particularly on our pension fund. So young guys will have to work for us to pay for our pensions. But this presents new opportunities because high-end services, building senior homes, and developing medical equipment and technologies, which will be highly needed. One thing that we are very proud of is that, even though China’s per capita income is only one-fourth that of the United States, our life expectancy has already beaten that of the U.S. That’s also a very interesting one to observe.

Our goals are built on a ladder. First, we aim for 2035, with the prospect that was already set forth during the previous Five-Year Plan. Then we also build on the second tier, which is the Second Centennial Goal: to build a moderately prosperous society and then shift into a fully strong and modernised socialist nation.

When people ask me how to interpret Xi Jinping’s “China Dream,” I say there are two dreams that are interrelated. One is the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation—people can compare it with “Make America Great Again,” but in a different approach. The other is to continue contributing to shared prosperity for humanity, which is very visible through the Belt and Road Initiative and now through the four new initiatives that you have already read about.

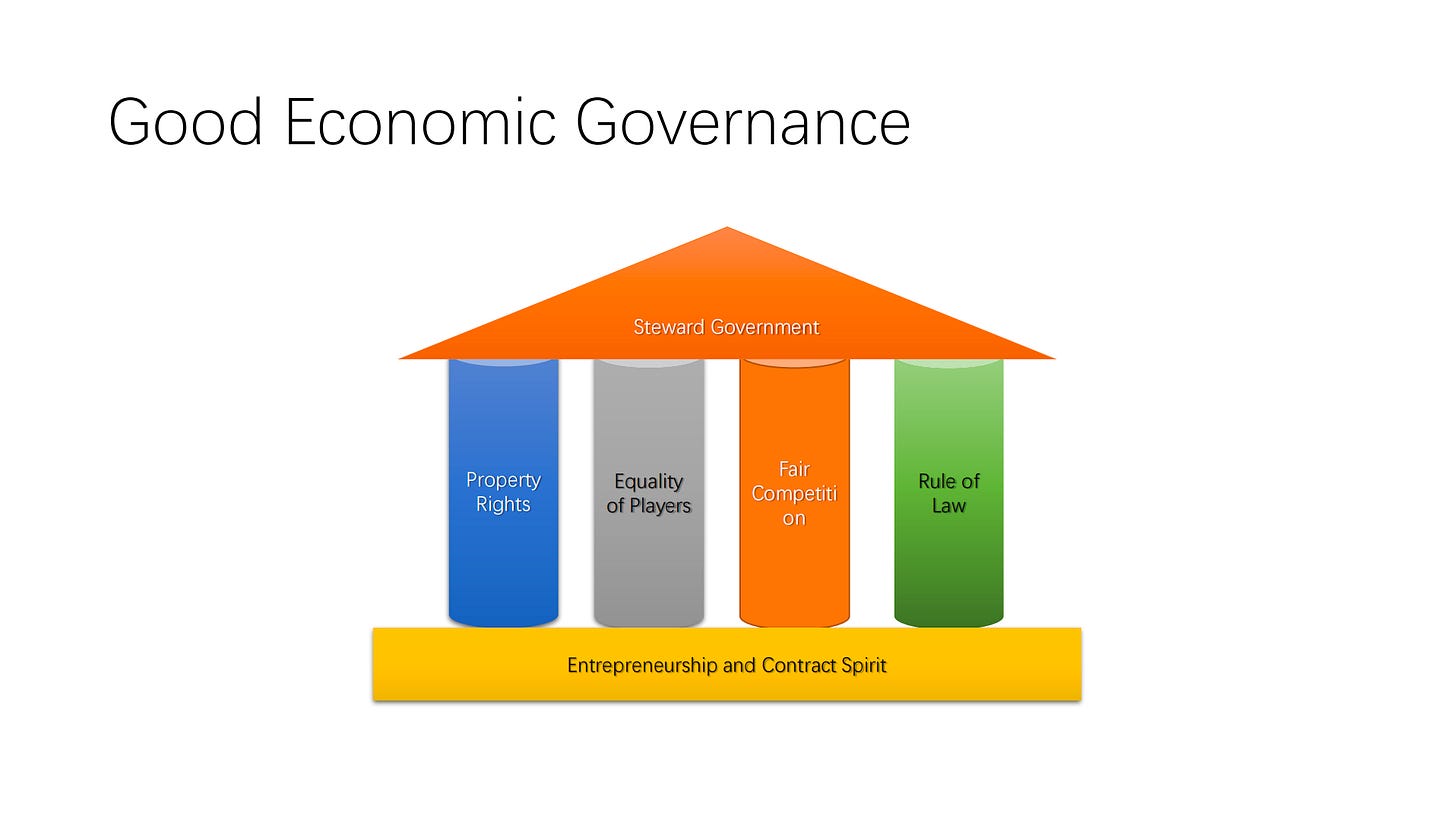

Strengthening governance is the first paragraph of the resolution from the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The next Five-Year Plan will be able to put it more into practice: to have clearly identified property rights and to build equal status and identity for different players. For example, now in China we have three types of market players: SOEs (state-owned enterprises), private firms, and foreign firms. Even for foreign firms, we now have 1.24 million foreign companies registered in China. So I strongly propose that we need to put them into one group in the next Five-Year Plan, to create an enabling environment for them to do business in a more transparent and cost-efficient way, so that our regulations and standards can really give them better predictability in making decisions. Only when you really treat every player equally can you have fair competition. You can’t just say, “Okay, I’ll give certain companies more subsidies or more franchises,” and then leave the rest to survive on their own.

Then, to have the rule of law. China is now shifting from a policy-driven approach to a more law-driven approach. This is important for giving more direction and predictability, not only for business people but also for local governments.

Finally, to promote entrepreneurship and the contract spirit. We will give misdirection on how we can move forward with dramatic shifts in policies. Then we can build a steward government.

One thing that people often ignore and take for granted is that the next Five-Year Plan makes it clear that economic construction is still at the core of China; it’s not all those ideological fights. So, it’s about bringing people a sense of entitlement through economic growth, improving the quality of that growth, expanding social welfare, and having the government produce more public goods. This is something we really need to go for.

Over the past few decades, China has succeeded through deregulation and privatisation, though in a different format. But now we need integration. We need to integrate education, research, development, manufacture and commercialisation into an industrial system. So, the new buzzword is to build the “industrial ecosystem” for the next Five-Year Plan.

For green transformation, we are not only committed to a clear timeline for carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, but most recently, China has also committed to a self-determined reduction of carbon emissions, which is called the NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution).

There have been many debates that China maintain both an effective government and an efficient market, but what is the demarcation line between the government’s role and the market’s role? I was saying that, Okay, let’s make a positive list for the government: just identify what you want to do, and otherwise, don’t step beyond the boundary. As long as the market functions, the government can take a rest.

In the end, it’s really institutional opening. We used to have an “open-door policy,” but now President Xi promotes “institutional opening,” which means that we are going to benchmark against higher levels of global norms—not only the WTO, but also benchmarks like the CPTPP, which we have been seeking membership, and the DEPA (Digital Economy Partnership Agreement), to improve digital efficiency and digital collaboration. With that, we can absorb all the wonderful things so that we are able to adapt them to China’s particular environment. We want to work more with the rest of the world.

The unified market is also at the top of the agenda of the next Five-Year Plan. To build a unified market is really to harmonise all different rules and regulations at the local level, in order to be better prepared to work with the rest of the world, instead of building a China market fortress. So, I think now I’ve reached the three-hour mark. Thank you. Thank you very much.

HUANG Yanghua, Professor and Deputy Dean of the School of Applied Economics, Renmin University of China

Good afternoon, dear guests. Thank you for the introduction. I’m from Renmin University of China. “Renmin” in Chinese means “people,” so the People’s University of China. I’m from the Economics Department, and my research focus is on industry. I’m very happy to join this event on technological innovation, industrial cooperation, and green transition. As we know, the world is connected by people, by ideas, by knowledge, and of course, by goods, business, and enterprises. Following Professor Liu’s overview of what China is going to do in the next five years, my focus is on the industrial system.

As mentioned by Professor Liu, just after economic construction at the core, the next priority is about the industrial system. You may be curious why the Chinese are so crazy about industrialisation. From economic literature, after the Second World War, when people talked about development, they were talking about industrialisation, because the world was divided into industrialised countries and industrialising countries after the 18th century. So there is a long history of economic studies about how to succeed in industrialisation. Even going back to Adam Smith more than 200 years ago in The Wealth of Nations, the division of labour within manufacturing is the source of economic growth.

A lot of research and countries have followed the path of industrialisation. For China, in the last 40 or 50 years, China has been a great economic power of the world and has succeeded in long-term economic growth. I am an industrial economist, so I try to think about China’s economic development as a long process of industrialisation.

We can see from this chart, the red dashes are the gross value added of the secondary industry, indicative of industrialisation. The blue dots are the growth of GDP. We can see for a long time since the opening-up in the 1970s, these two curves are strongly correlated. So when business is good, the economy is good. China’s economic growth is a typical industrialisation-driven model. So when China talks about industrialisation, it is talking about long-term growth or long-term development. This is a fact.

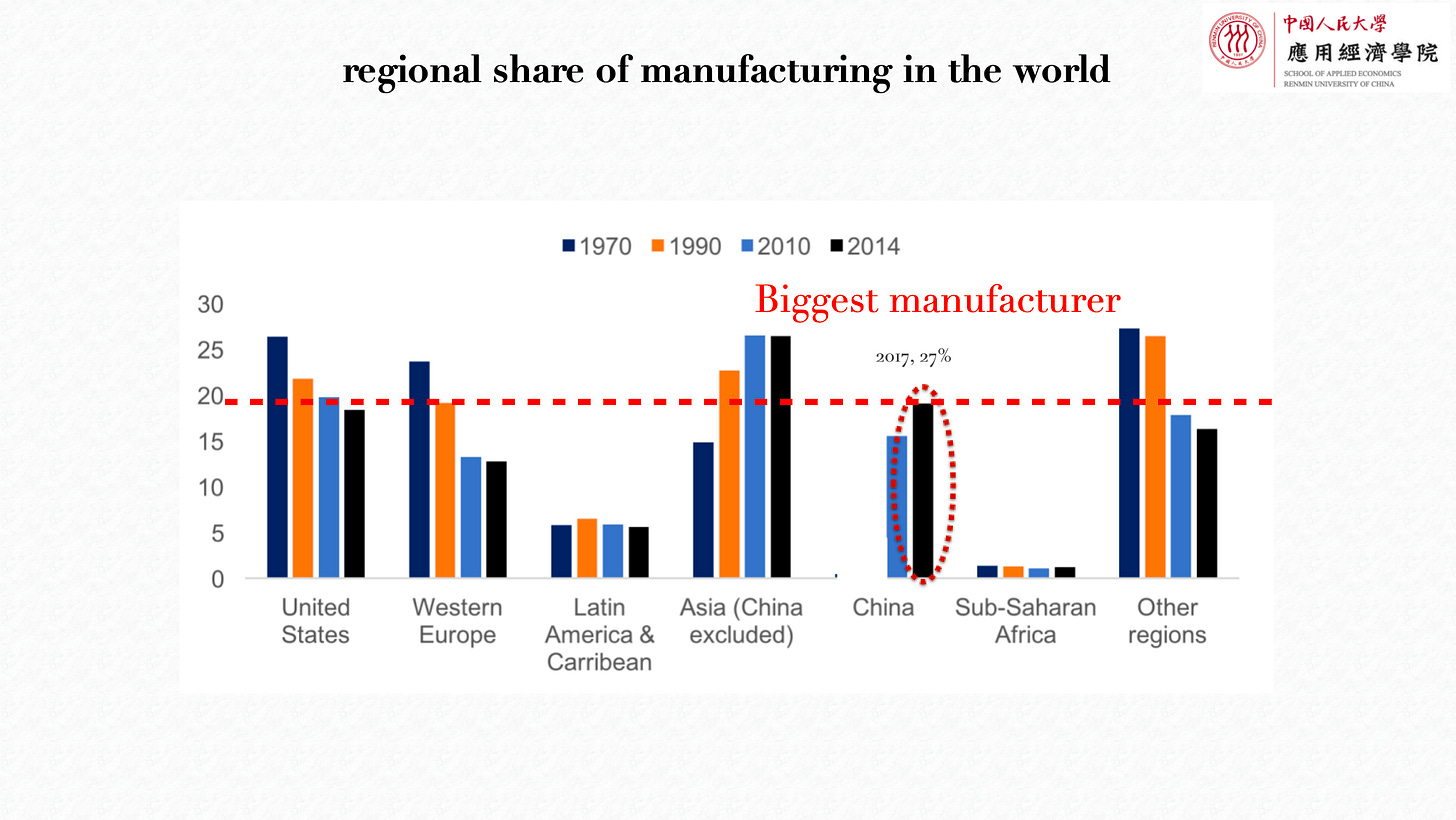

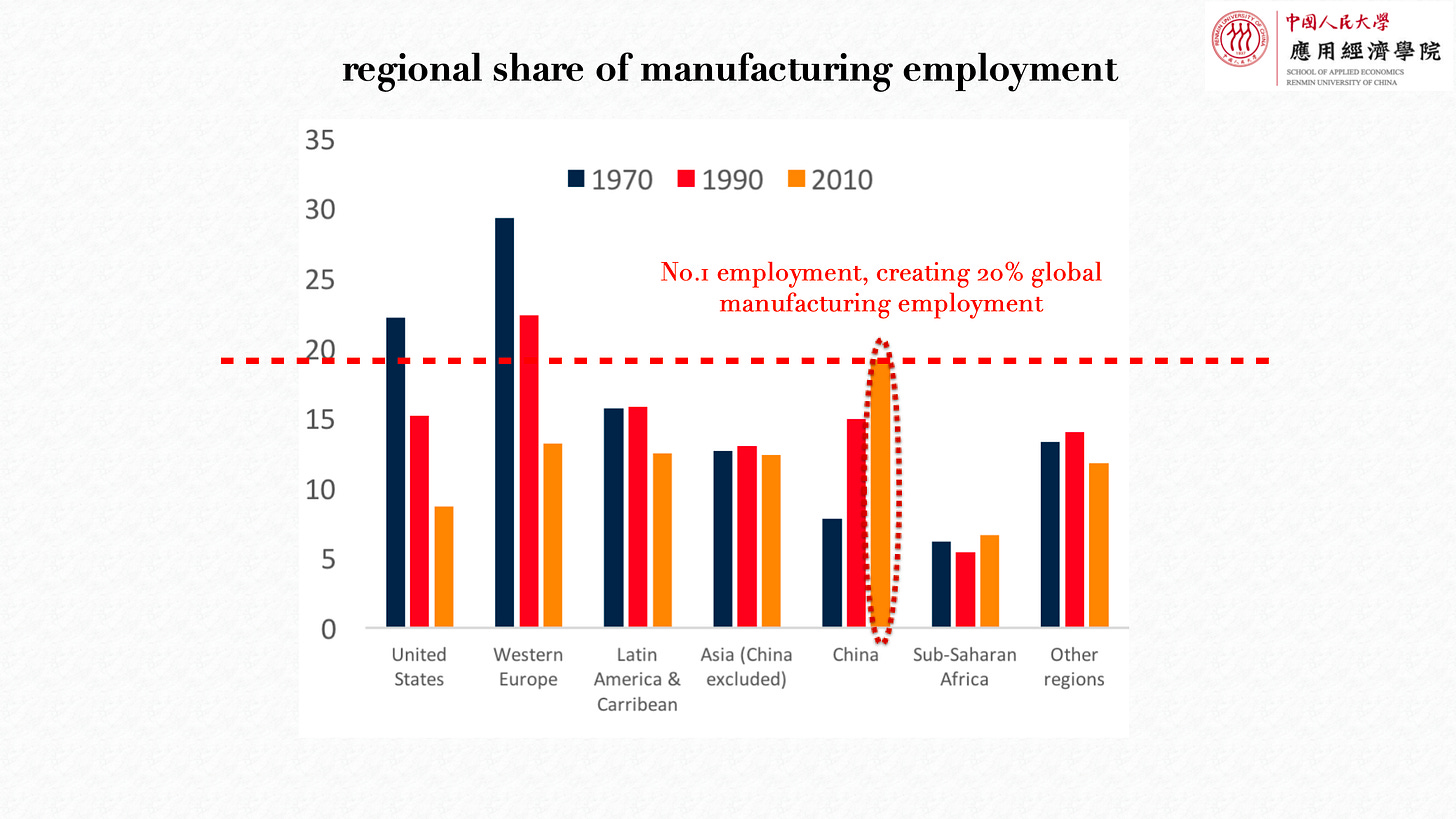

Let’s take a look at the world’s industrial economy back in the 1970s. This is the regional share of manufacturing in the world. We can see that back in 1970, the United States was the biggest industrial economy since the end of the 19th century.

But since 2010, China has become the largest one, surpassing the United States. This is the first time in a hundred years that the United States has lost its first place in industrial economics since the 19th century.

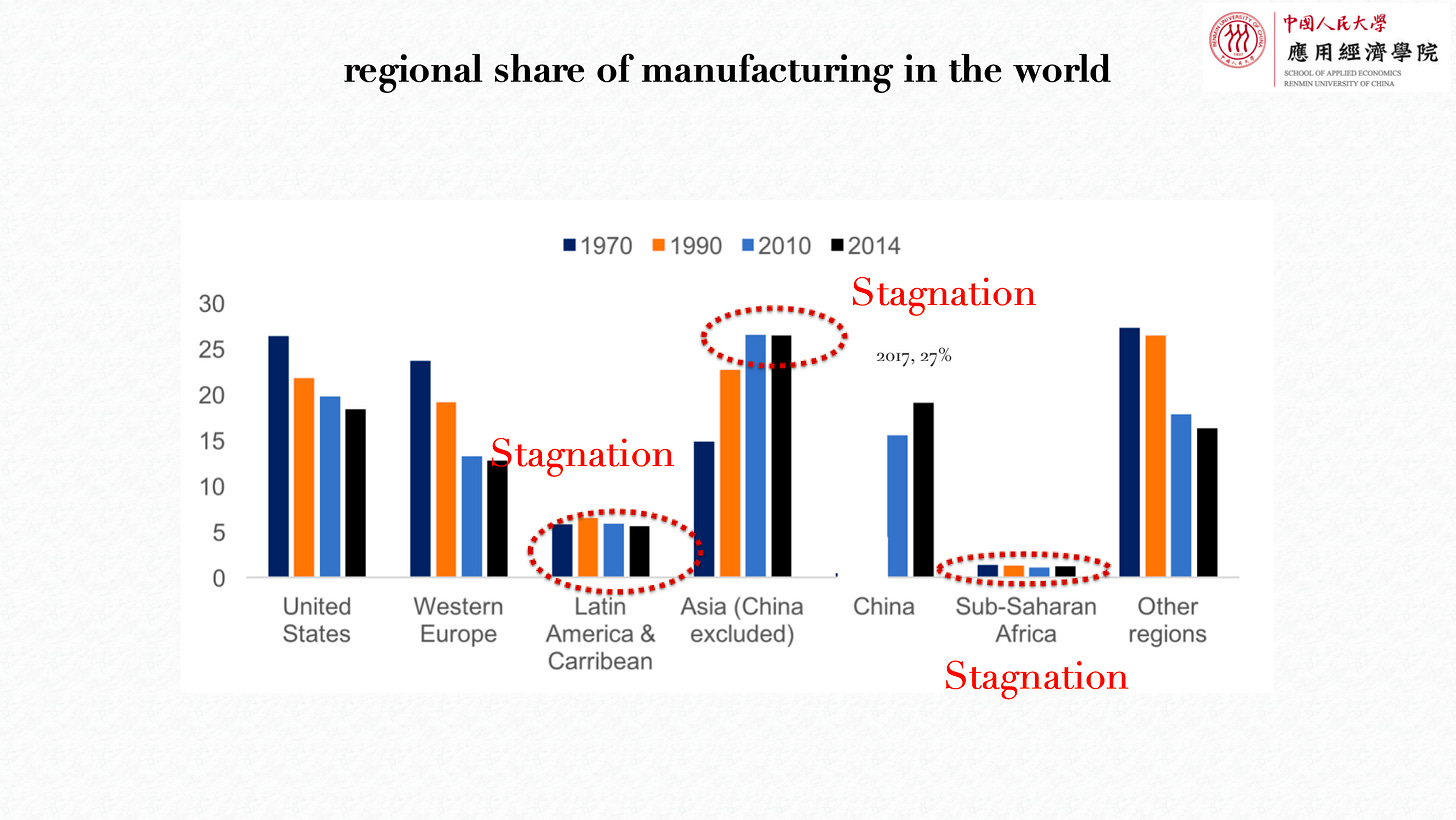

Now I will show you the latest data. We can see the regional share of manufacturing for other developing regions, for example, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Latin America. They are also doing well in economic growth or industrialisation, but the share of these regions in the world has stagnated, which means they are not growing as fast as some developing economies like China.

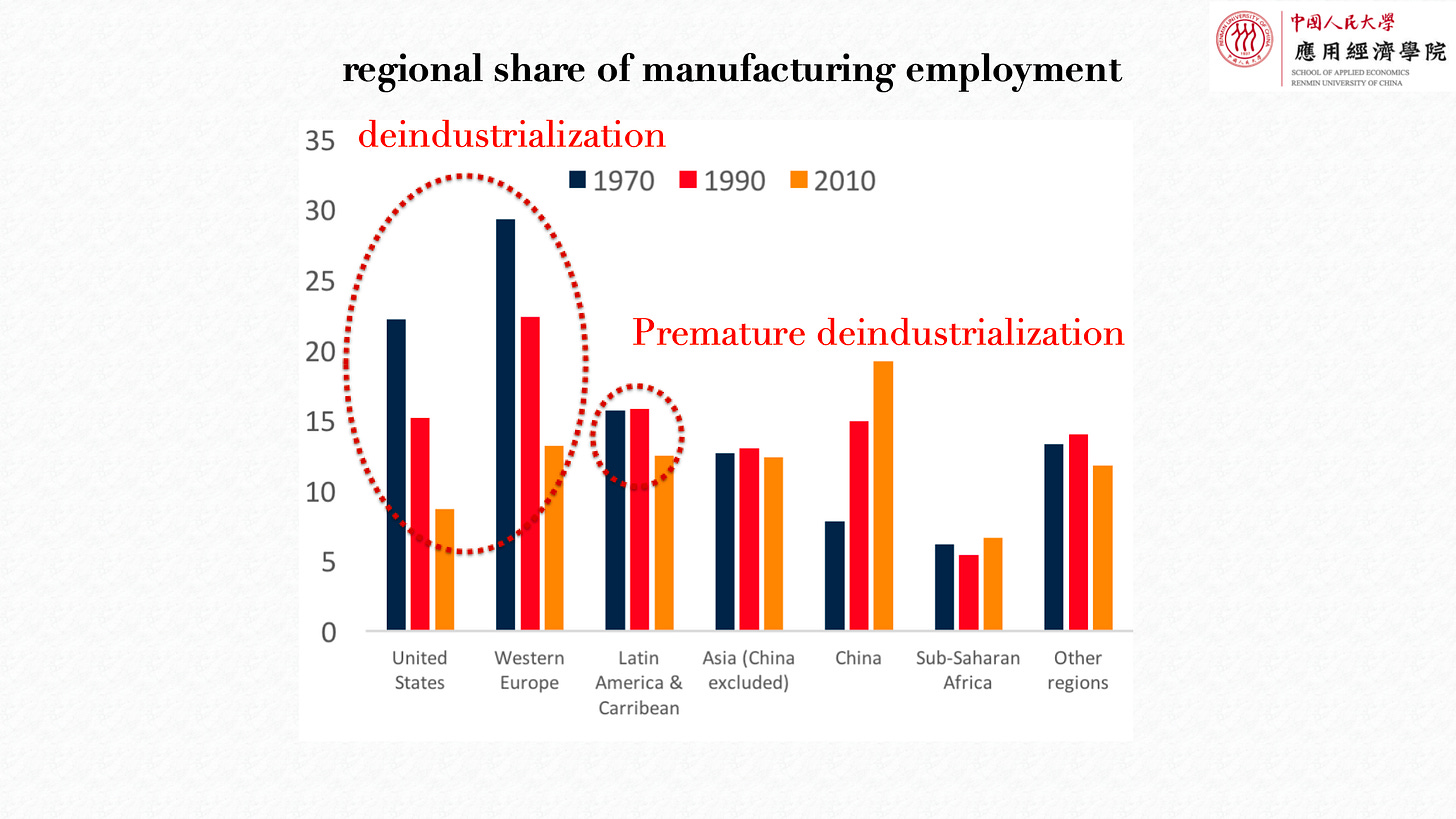

This is the regional share of manufacturing employment. We can see that in the United States, there were a lot of blue-collar industrial workers in the 1970s, but the number has decreased very quickly. China is now the largest employer of manufacturing workers in the world, contributing about 20% of manufacturing employment.

We can see that in some regions of the world, like the United States, the European Union, and Latin America, manufacturing employment has been declining for a long time. We call this process deindustrialisation, which means more and more people are shifting out of industry and working in services or other businesses. There are also some Latin American countries that have experienced deindustrialisation, but they are still in the process of developing. We call this kind of deindustrialisation “premature” deindustrialisation. So, this is an overview of the world’s industrialisation.

And China, of course, has been the “world factory” for at least 20 years, especially after joining the WTO in 2001. I will give you a brief introduction about the achievements of industrial growth in the last five years, that is, the 14th Five-Year Plan. We can see that China has been the largest industrial economy since 2010. In the last five years, and even in the last fifteen years, China has remained the largest industrial economy, and China’s industrial economy, especially manufacturing, has kept on growing. Now, the share of China’s industrial economy in the world is 30%. Back in 2010, it was 20%, but now it is 30%. The size of China’s industrial economy is the sum of the United States, Germany, and Japan.

China’s industrial economy keeps on growing as well as upgrading. We can see that the high-tech industry’s growth rate in the last five years has been more than 5%, which is equivalent to GDP growth. As GDP grows, the high-tech industry also continues to grow. In 2024, the growth rates of equipment manufacturing—the core of the real economy—and high-tech industries are even higher than GDP growth.

In terms of an innovation-driven economy, we can see that a lot of resources and talents are allocated to innovation. The R&D intensity is 1.6%, getting close to the OECD level. A lot of innovation institutions and centres were built up boost business innovation as public goods.

We can see that China is moving towards high-end and smart competitiveness. The 5G network is an indicator of digitalisation, and China’s 5G base stations account for about 60% of the world’s total. And we can see a lot of emerging technologies come out every year. Some of the breakthroughs are the first in China, and some of the breakthroughs are the first for humankind, for example, the lunar exploration. China is doing a lot of “firsts” for the whole world.

And we can see China’s industrial competitiveness and global leadership in the “new trio.” The production, sales, and global market share of electric vehicles (EVs), photovoltaic (PV) products, and batteries have all grown rapidly in a very short time. China’s market share in these sectors is expanding very fast.

And about sustainability. It used to be that manufacturing meant being dirty and polluting. But we can see that after a lot of environmental regulations, the consumption of energy, water, land, and fossil fuels in industry has decreased and will keep on decreasing for the next five years.

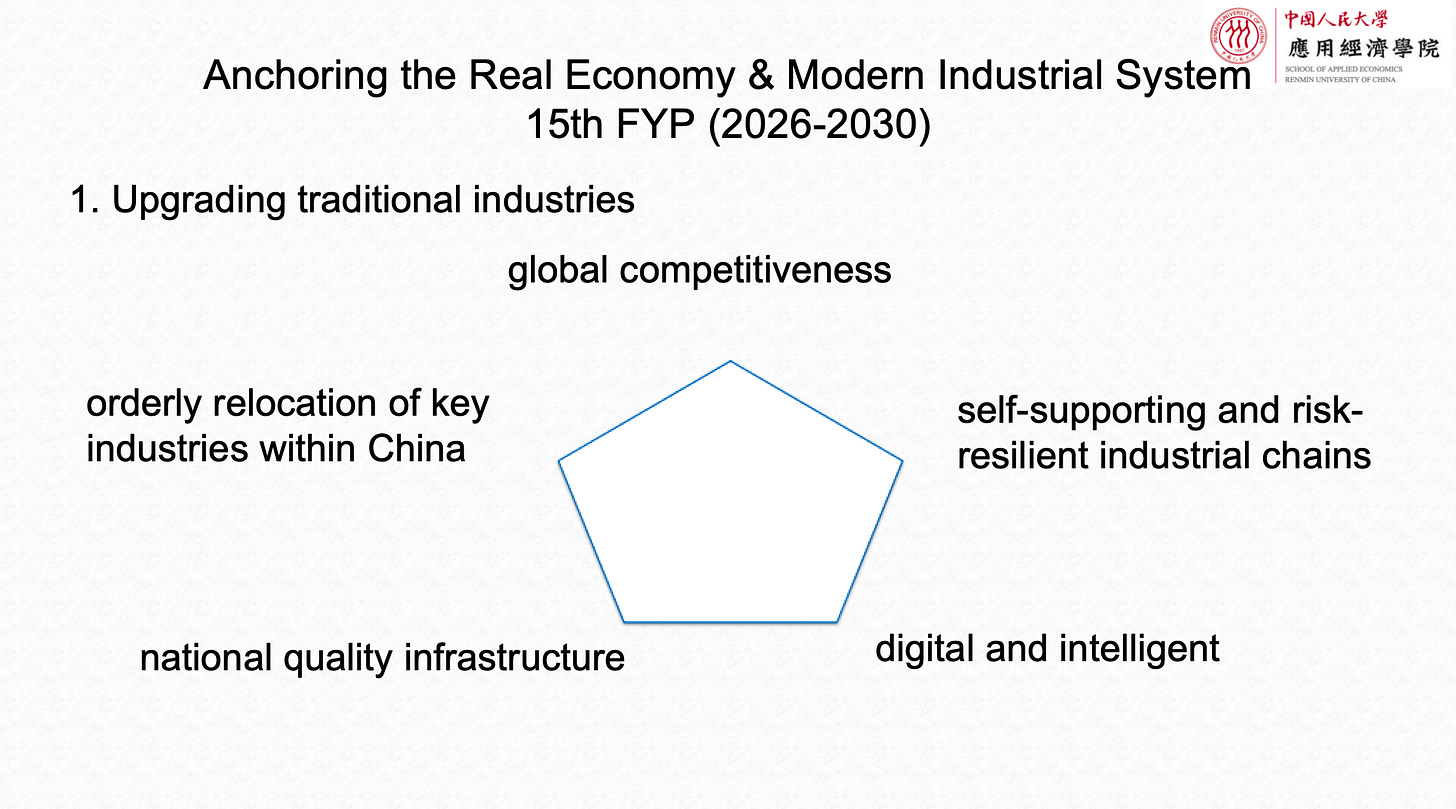

This is what we call an achievement of the industry in the last five years. Based on this, let’s look forward to the next five years. From the text of the Recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China for the 15th Five-Year Plan, the position of industry is an anchor of the real economy and the modern industrial system.

The “real economy” is not an economic term but a policy term. In China, the real economy means manufacturing at the core. That means real estate and finance are not the real economy; they should develop in ways that support the real economy. Otherwise, there may be regulations on real estate or the financial sector. Only if the real estate and financial systems support the real economy will they be encouraged. So this is a key message.

I will give you a very short briefing about what China is going to do in the next five years in the industry. The first is about upgrading traditional industries, because traditional industries are very important for stabilising the economy and especially for creating enough jobs and opportunities for people to have an income. But these industries need to be upgraded; otherwise, there will be a lot of competition and pressure from the global market. Here are some directions for upgrading traditional industries.

I think some of you may focus on the orderly relocation of key industries within China. Some people are talking about the overcapacity of Chinese manufacturing: why does China still keep so much production inside the country? They should be shifting it out. We can see here that key industries should be relocated from the eastern part of China to the mid or western part of China. Some low-end—that is, low-productivity—manufacturing will keep on shifting to other developing countries, for example, Asian countries or African countries. China will just focus on the key industries; that is very important for the productivity and security of the industry.

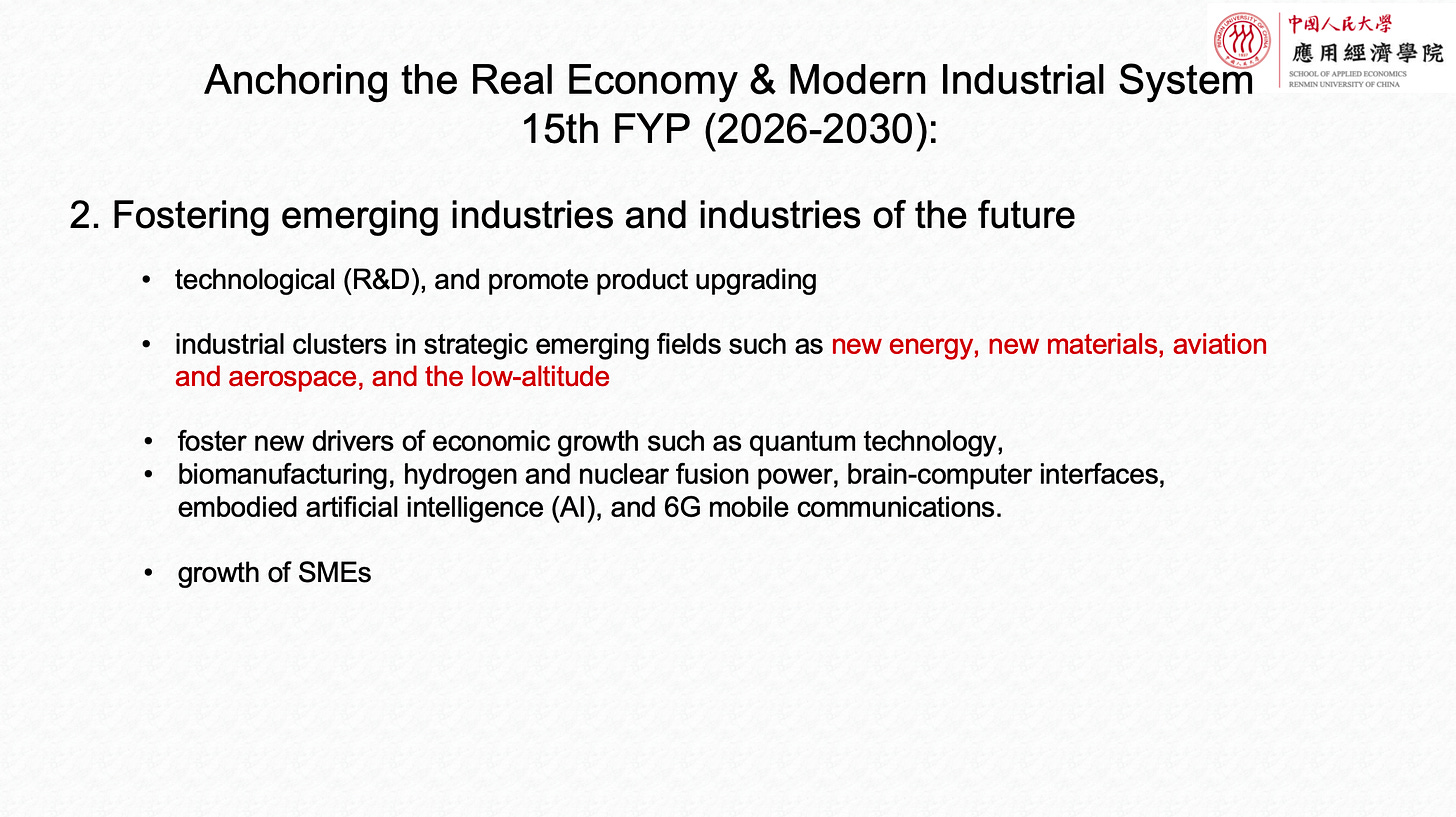

And the second point is fostering emerging industries and “industries of the future.” “Industries of the future” is also a Chinese term, which means that Chinese policy focuses on new engines of growth in the next stage of development. Here are some examples: new energy, which is very important for the green transition; new materials; aviation and aerospace; and low-altitude industries such as UAVs. These are very important for industry and social governance. Here are some new technologies that should be industrialised in a short time. For example, AI and quantum technology are breakthroughs achieved in laboratories. How to bring them into the market is the next focus of the industry.

And of course, there is also the modernisation of the infrastructure system. Why is the infrastructure system so important in China? Because China is a large country. Infrastructure is very important for integrating the market and making the whole national market a unified one. Here are the new types of infrastructure, especially digital infrastructure, based on the digital economy. Of course, traditional infrastructure like transportation and the electricity system should be digitalised to make them much more productive and environmentally friendly. Here are some other systems of infrastructure. Overall, China’s infrastructure will be upgraded to make the economy much more productive and more environmentally sustainable.

This is my key message for you about the Chinese economy. Thank you very much.

WANG Zhi, CCG Senior Fellow; Visiting Professor at the Institute for Global Development, Tsinghua University

Just as Professor Liu has discussed the overall picture of the next Five-Year Plan, I will concentrate on the green part of the plan.

The key themes of the proposal of the Central Committee are the guiding principle is to make green development a defining feature or the core background colour of Chinese-style modernisation. The core driver is the dual-carbon goals: carbon peaking and neutrality, which serve as strategic pivots guiding a synergistic push to reduce pollution, expand green coverage, and maintain economic growth.

The energy foundation is to build a new clean energy system—a strategic shift toward a modern energy infrastructure that is secure, efficient, and clean, fundamentally transforming how energy is produced and consumed. That’s the goal.

The economic engine is expanding green manufacturing and green trade, while at the same time developing green finance to support this transition. The social shift involves fostering a green, low-carbon lifestyle and consumption pattern. The global dimension focuses on promoting high-quality Belt and Road cooperation, aiming to turn China’s green transition into a global opportunity for shared development and climate action.

These are the main themes, the blueprint. But how can they be implemented concretely through financial, economic, and trade policies? As a think tank, CCG must think ahead. I have had detailed discussions with Huiyao and Mabel in London, and we propose a Global Green Industrialisation Initiative (GGII). That’s what I will discuss today, as the international implementation framework for the 15th Five-Year Plan’s green development goals. Through this implementation, we aim to achieve the goals laid out by the Central Committee, transforming China’s domestic transition in green technology into a platform for inclusive global cooperation, shared growth, and collective climate action.

So, why are we talking about this? Why are we proposing the Global Green Industrialisation Initiative? I will briefly outline our thoughts. I will mainly discuss two questions: why we need this initiative and how to implement it. We will also address Western concerns, the market potential of the Global South, China’s green energy capability, and how we can achieve global win-win results through green cooperation.

Green and low-carbon development is the shared interest of all humanity in facing the challenge of global warming. For Europe, it is advancing its climate agenda with a 90% emissions reduction target by 2040. Its Clean Industrial Deal aims to decarbonise manufacturing with a major push for renewable energies, adding 100 gigawatts of capacity annually, and to ensure that renewables account for at least 42.5% of total energy consumption by 2030. However, there is still a 1.5-percentage-point gap remaining.

For the United States, the current administration has terminated federal wind and solar subsidies, casting uncertainty over its clean energy transition. For the Global South, these countries face dual challenges of achieving growth while reducing emissions. They need to explore a new green industrialisation pathway powered by renewable energy. For China, at the Global Climate Summit, President Xi reaffirmed China’s commitment to cut economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions by 7–10% below the peak level by 2035. By that year, non-fossil fuels are expected to account for over 30% of total energy consumption, and installed wind and solar capacity will be more than six times the 2020 level. That means this is truly a shared goal for all human community.

For this initiative, we will take all parties’ concerns into account. The West has legitimate concerns and anxieties about investment. For example, in the process of green transition, there are risks of displacing workers in major traditional industries like automobiles, steel, chemicals, and oil. These sectors remain major sources of employment, so the U.S. and Europe are worried about what they call the “second China shock.” We think this concern is legitimate—these industries are the pillars of their employment base. If China’s low-cost EVs enter those markets, they fear that it could destroy their employment foundations. That’s a real concern.

Another concern is competitiveness. Many worry that stricter environmental regulations in the West could raise production costs, undermining the global market position of domestic manufacturers. This is a real issue. The EU does have more stringent environmental regulations than many countries in the Global South. Therefore, these realistic and legitimate concerns should be carefully considered in the design of global green industrial policies.

For the Global South, they have the right to development. Developing countries have a legitimate right to grow. They say, “You polluted in the past; now it’s our turn to develop.” But following the traditional path could trap them in high climate risks and costly future adjustments. Now, however, they have a green alternative. With adequate support, they can adopt a low-cost, sustainable green industrialisation model, a new model now emerging in China. China has learned from its own experience: “pollute first, clean up later.” That path came with very heavy environmental and public health costs, and it shows the need to embed sustainability from the beginning of development. I remember in 1999, when I brought my 13-year-old daughter back to Beijing, as soon as we got off the plane, she asked, “What is this?” because of the dust. It was hard for her to breathe. China paid a very high price for that, but now, Beijing’s air is much cleaner than it was twenty years ago. This improvement has come from China’s persistent investment that led to technological breakthroughs and mass production in solar, wind, and battery industries, which have driven costs down dramatically. This experience proves that green and low-carbon development and economic growth are complementary and can be pursued systematically.

Twenty or thirty years ago, green technology was considered a luxury because, at that time, it was too expensive for developing countries to follow the same path as the West. But now, because of China’s heavy investment and persistence over more than forty years, you can see the change in cost. The cost of solar energy, wind power, and hydropower has dropped significantly. In fact, only in hydropower is China’s per-unit cost higher than that of the EU. For all other types of renewable energy, China’s costs are much lower than the world average. That means that now, because of China’s innovation and mass production, green energy has become affordable, and China has achieved global leadership. Even in solar and energy storage technologies, China now holds both technological and cost advantages, making it possible to help Global South countries bypass fossil fuels and build cleaner, more sustainable energy systems powered by renewables.

You can see this picture; it’s really interesting. This is from a very recent report just published on the Internet. It shows that 20 African countries imported a record amount of solar panels in the past twelve months, that is, from last July to this June. You can see a very sharp increase. This picture comes from a very authoritative source in energy development data, called EMBER. This represents a real-time transformation. According to the report, Africa imported a total of 15,000 megawatts of solar panels from China, an astonishing 60% increase, signalling rapid acceleration in the continent’s solar industry.

This trend has a few important features. First, it’s the world-speed growth. The twenty African countries have set new import records, with Algeria up 33-fold, Zambia 8-fold, and Botswana 7-fold, indicating a continued, continent-wide green energy wave. They also show huge transformation potential. These imports can reshape the energy landscape once fully installed. For example, in Sierra Leone, they could generate 61% of the country’s total power output in 2023, and contribute over 5% of total power generation in 16 other African nations. As for economic feasibility, according to the report, in Nigeria, the payback period for solar panels, when replacing diesel-based generation, is only six months, enough to recover the investment. This demonstrates the emergence of a mutually reinforcing partnership between China’s competitive green manufacturing capacity and Africa’s urgent development needs, driven by economic incentives rather than external subsidies.

So, these data clearly illustrate that the Global Green Industrialisation Initiative (GGII) targets a real, economically viable transformation already underway, rooted in real demand and shared global interests. This is a historic opportunity that we must seize.

Then we see the potential of the Global South. Based on data published by the International Organisation of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA), the projected global vehicle stock in 2025 is like this. We just go to the picture. The United States is 18%, Europe is 17%, China is 22%, and the other countries are 43%. If those countries achieve the electric vehicle penetration rate of more than 40%, then this will be a larger market than the U.S. and the EU.

Then we see the capacity of China’s green industry. The policy framework is already outlined. Basically, it is to jointly build a high-quality Belt and Road Initiative, enabling countries around the world to share development opportunities and pursue common prosperity. You see, in solar energy, China accounts for 86% of global solar module production, 97% of silicon wafer production, and 91% of solar cell capacity. China’s ultra-high-voltage transmission technology enables long-distance power transmission with line losses of less than 5%. This is demonstrated by a project successfully implemented in Brazil.

Then you see the new energy vehicle capacity. As of the end of 2023, there are 361 automobile manufacturers operating in China. Among them, 265 are domestic, 95 are joint ventures, and 1 is a foreign-invested enterprise. Among the foreign enterprises, there are 38 from Europe, 21 from Japan, 15 from the U.S., and 12 from South Korea. So you see, when some Western observers talk about the “overcapacity” of Chinese EV production, look at the distribution: about 43% is joint venture capacity, which means those are foreign companies coming to China. When China tried to industrialise, it used the market in exchange for Western technology.

So I’m talking about the necessity of green industrialisation. What is the pathway? First, we should encourage Chinese green firms to invest in the EU and U.S. markets. The benefit is to reduce the trade imbalance. In 2024, China’s auto exports were around 44–54% complete vehicles, and the rest were parts and components. So we should encourage Chinese firms to invest in local manufacturing plants for green technologies, including new energy vehicles, solar modules, and energy storage, in the U.S. and European markets. This directly creates local jobs and strengthens regional supply chains.

We suggest that the West adopt a “market-for-technology” joint venture model. China’s proven “market-for-technology” approach during the internal combustion vehicle era offers a strategic blueprint. Back in the 2000s, China’s automobile industry was very backward. Through joint ventures, it used the market to exchange for advanced technology from the West. It was quite successful; it trained Chinese workers and accumulated human capital in management and technology. So now it’s time for Europe and the U.S. to open their markets to benefit from China’s advanced green technology by establishing localised production and joint ventures. Advanced Chinese technologies can be integrated into European and U.S. industries. This approach will help meet local decarbonisation goals, pool technological and financial resources, and share both risks and benefits among partners.

This idea has three very tangible benefits for the West: introduction of advanced green manufacturing capacity and high-quality jobs; a more resilient and cost-competitive green supply chain; accelerated progress toward energy transition and emission reduction targets. China should prioritise pilot projects in regions with political alignment, using demonstrable and successful cases to build trust and cooperation. While political hurdles remain significant in the U.S., we think the EU, with the foundational China–EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), offers a viable starting point. Efforts should focus on reviving the CAI ratification process, ensuring market access, fair treatment, and robust intellectual property protection in green sectors.

Then we see the Global South. The key problem for the Global South is: Where does the money come from? They have no money. Many countries in the Global South face low sovereign credit ratings. If they borrow in the international market, the rate will be around 15% to 20%, making it very difficult or even impossible for their governments to raise funds. Also, in those green sectors, these countries do not have established green firms with a credit history, which prevents commercial bank lending.

The dollar dependency also creates problems. Most loans are in dollars, and high U.S. interest rates combined with exchange rate volatility create unacceptable costs. Meanwhile, Chinese financial institutions also face operational constraints overseas. They often prefer domestic real estate as collateral, and they face dual regulatory burdens from both Chinese and local authorities, which sometimes conflict. Their local presence and service capacity are also limited. So in reality, reliance on government fiscal aid and intergovernmental loans is unsustainable. Market-based solutions and financial innovation are urgently needed to break this financing impasse.

I know my time is limited, but let me briefly talk about the Chinese model. It provides a practical pathway. The model is to provide RMB loans to domestic green enterprises, including joint ventures, which then make direct investments in Global South countries. This approach has low credit risk, reduces financing costs, and effectively mitigates sovereign risk.

Because, as you said, I’m sure how to interpret this—it’s about joint ventures as overseas pioneers. These ventures possess international brands, mature sales networks, and risk management experience. Years of cooperation with Chinese enterprises in China have built a solid foundation of experience and mutual trust. Facing market share and profit pressure in China, for example, in the EV joint venture sector, they have a strong motivation to explore new overseas markets.

Okay, my time is up. This is about how to implement and who will implement, and then how we can build a triple-win cooperation. That way, we can form shared technologies, unified global standards, expanded Global South manufacturing, worldwide sales, and global services. This will create a new paradigm of South–South and North–South cooperation for industrialisation, achieving mutual benefits and a triple-win outcome for China, the West, and the Global South.

Q&A

Rol Reiland, Ambassador of Luxembourg to China

Thank you very much for organising this interesting event, and thank you for the three very insightful presentations. In the interest of time, I would limit myself to the last one, to the one of Professor Wang's. I would start by already inviting you, because you didn’t have the opportunity here. I will organise an event, a breakfast event or whatever, and we will find a solution to discuss some of those issues in further detail, if you agree. Particularly, the one on finance, obviously, given where I’m coming from.

But maybe a more general question now to you: we have all seen the tremendous development of China in green technologies, and also, as you explained so well in your slides, the effects this is showing now also in the Global South, in helping the Global South not only to increase access to energy but also to decarbonise. But then, when we look at China’s announced NDCs—to reduce its carbon emissions between 7% and 10% by 2035—many observers were kind of, well, China has the habit of setting goals that are not too ambitious and then trying to overachieve, as we have seen with the peak carbon as well. How would you see that? What would you tell those observers who say that, in order to reach the 2-degree limit, given that China is the largest emitter, China would have to reduce at least 20%, and for the 1.5 (-degree limit), at least 30%, of its emissions? Does China have the means to do so by further accelerating its efforts?

And related to that, I have also seen some first comments about the 15th Five-Year Plan from some commentators who say that the ambitions of China regarding green development and developing of green technologies don’t seem to be that high anymore as they used to be. How would you respond to this, given that the green sector last year has taken 10% of China’s GDP? Thank you very much.

Thorir Ibsen, Ambassador of Iceland to China

Thank you very much, Dr Miao, and thank you again for bringing us together for useful presentations. I have a question for Professor Liu and Professor Huang. The emphasis put on the new industrial ecosystem in the Five-Year Plan—two questions about it. Could you elaborate a bit more on what is the difference between that concept and China’s industrial policy up to date? And secondly, and that may not be a very favourable question, aren’t you worried that it is going to call for more criticism of China for subsidising overproduction? Thank you.

Djauhari Oratmangu, Ambassador of Indonesia to China

First of all, thank you, Mabel, for inviting me and all of the colleagues here. I have two questions. Number one, to the first two professors: because I concentrate more on the economy and then how to distribute equally the cake, is there any intention as well to distribute the cake to regional cooperation? That’s number one. Number two, Professors, it looks nice on paper and presentation. I’ve been doing this. It’s difficult to do it in the implementation, because I travel a lot to meet a lot of those industries. Mostly, their idea is to sell the products, not to have a collaboration or investment. That’s my impression. So, your presentation is nice on paper only. Thank you.

WANG Zhi

Okay, your two questions. The first question: because China is a large country, there are many competing interest groups, especially in traditional industries. So the central government is very careful; they don’t want to set a higher goal and then fail to achieve it, because that would make them look bad. That’s the reason.

But actually, I think that relates to your second point—that’s a misunderstanding. If you see the Central Committee’s proposal for the 15th Five-Year Plan, they said that green is the background colour of Chinese-style modernisation, so they will promote it not only in the industry. They concentrated on the industry in the past, but right now, they are gradually moving to the whole society. They encourage people to have a healthy lifestyle and to reduce energy consumption. From my reading, the Central Committee is very resolute in reducing carbon emissions. They will achieve the carbon goals, and it’s possible they will even accelerate the process.

Of course, there are compromises between China and the West, because China has a very large domestic market. So, the Global South really needs this kind of knowledge. Globally, there is a much larger market that is far more than enough. We should produce more, but jointly. You see, the Deputy Director of the OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate told me they cannot allow just one producer to produce 90% of the global supply—that’s what they’re worried about. But this is a misreading. When we say China produces 91%, it’s not from one company; it’s from many different segments and enterprises. The reason why the Chinese industry is so competitive is because they first survives in the Chinese market. If you can survive in the Chinese market, you can survive anywhere internationally. That’s real competition.

But this can be negotiable. We really hope the EU can take the lead in allowing Chinese green industry firms to invest in Europe, which will strengthen Europe’s competitiveness.

Maybe then I will respond to the second question. You see, it’s not only on paper. I believe when I talk to some Chinese experts, they really want to help the Global South’s industrialisation, and this is consistent with China’s own interest. Why? Because you see, China’s industrialisation basically involved moving rural peasants into industrial sectors, which doubled their productivity and income, and created a larger market. If you think about the Marshall Plan after World War II, the U.S. had a large manufacturing capacity. During the war, they made planes, tanks, and warships. After the war, their Marshall Plan actually rebuilt Japan and Europe. And by doing so, they created markets for U.S. industrial capacity. China now has the same interest in helping the Global South become industrialised. When countries in the South have more money, they can afford more equipment and technology from China because it is much cheaper than Western technology.

LIU Baocheng

To address some of the issues raised, I think I’m not as optimistic as Professor Wang, because China is now having a buzzword about “involution”. Involution is a result of redundant capacity. There’s no doubt about that. And now, we have 159 e-car companies; many of them will have to continue to die. The predatory practice in the global marketplace is already being negatively felt. I think that’s something we need to deal with.

Of course, innovation also brings about Darwinism: those cars that are not really competitive will be washed out. That’s my observation, because five years ago, we had 474 car companies, and now we already have 169. So that’s one thing.

My other concern is how we can recycle those batteries. So far, I have not really received or accessed to any type of convincing solutions over those batteries. I think the whole world really needs to be watchful about that. But I’m also hopeful that, given the time, we are going to have a better solution to all those issues.

Then, regarding Chinese commitment to carbon peaking, I think you rightly pointed out that there have been a rescinding type of voices with regard to the green commitment. Because every country has to balance between a reasonable level of growth versus environmental commitments. And China at least deserves some sympathy, if not appreciation, because we manufacture 34% of the whole world’s gadgets, which means we buy a lot of resources from the world—be it energy, iron ore, etc.—and also we dump a lot of garbage. This means we are still largely in a blue-collar stage. We eat a lot, we piss a lot, and we doodoo a lot. Therefore, the next stage is how to recalibrate our digestive system and our urination system, so that we can be more cost-efficient and energy-efficient. There’s still a large space for us to do that. So, definitely, I think the commitment of the NDC is a voluntary one; it is based on deliberate calculation and also with some conservation. So definitely, we are going to be able to deliver on that issue.

And with regard to the regional disparity issue, I think the biggest problem is the divide between rural areas versus urban areas, because of the hukou system. I really hate this system because this is something of a posit. People are born with different treatment. Rural students who have poorer education need to get higher scores than citizens in the urban areas to be recruited to my university and other universities. That’s totally unfair.

Fortunately, after the alleviation of extreme poverty, now the rural revitalisation program is on the top of the agenda. From my observation, there are two positive signs: one is that there are more and more trees in the Chinese countryside. It used to be that a farmer’s household could only have three years of control over their land. Of course, they use a lot of fertiliser, and they don’t grow trees. Now they can be entitled to 30 years of control of the land; therefore, they have a longer period of planning, and they know how to raise the fertility of the land. So the system is really creating a very positive change.

The other is the introduction of many mechanics and artificial intelligence to help those farmers so they no longer use the plough to deal with the land or sickles to deal with the harvesting, etc. This is really a tremendous improvement, supported by the connectivity program. The “last mile” from highways to villages is already being covered. I was born in a small village in Hebei Province, and my nephew, who continues to live there, is so excited that, last year, for the first time in 5,000 years, they had access to a gas supply last year instead of continuing to burn charcoal and stalks. That’s really a positive one. But do not expect dramatic changes. That is why we maintain a steady way of changing. Look at how the Soviet Union collapsed, because people normally don’t have the patience to watch the gradual change step by step. And that’s why China manages its success. So, let’s go for it. And you guys are really contributing to communication and collaboration with China from all over the world. So let’s go for a better result for the globe and for humankind.

HUANG Yanghua

Okay, just a short response to the questions before we can have the second round of Q&A. So, the first is my response to the industrial ecosystem. I think the essence of the industrial ecosystem is about integration. For example, we focused on production too much in the past, but now we need to integrate the demand side and the supply side.

The second type of integration that we need to integrate R&D inputs and scientific research with production.

The third type of integration is between the real economy—the factories—and digital infrastructure. More and more factories will go smart and intelligent. And, of course, we need to integrate the financial sector with the real economy.

So, by bringing all these integrations together, the industrial ecosystem will be set up. It is quite different from focusing on factories only. This is my understanding of the industrial ecosystem.

Second, about overcapacity. As an economist, I’d like to say that overcapacity is quite normal for a market economy. If the demand always equals supply, there will be no need for the market system or the price system. So, the question about the Chinese overcapacity, I think that is also the problem of the integration of the Chinese supply and the global market was not working quite well.

Second, the Chinese local governments have some policies to encourage investment in their region, to create employment, and to raise taxes. So there are 30 provincial and 300 city governments in China. So if there is no coordination between the different governments, industrial policy will lead to overcapacity. So, how to deal with this is that the central government should be much more active in coordinating local governments’ policies.

The last response is about the dispute over how to divide the cake, after the cake has grown larger. We do a lot of research on China’s regions and rural areas, and we do a lot of research in Xinjiang and in Tibet. We can see there are two kinds of what we call “equalisation.” The first is the equalisation of public services. We can see that many people living in remote parts of China, in remote villages, also have access to universal healthcare and education. For example, students in Tibet and in Xinjiang pay nothing for their schooling, and when mothers are going to give birth, they pay nothing to the hospital, because all the costs are covered by the government.

The second type of equalisation is in public infrastructure. For example, when I go to Mount Qomolangma, the top of the world, I can do a livestream there, so we can see that 4G, 5G and many other kinds of public infrastructure are quite good everywhere in China.

Second, we can see that it is not only the government that provides public services and public infrastructure. There is also a very important channel for achieving these two kinds of equalisation, and that is the state-owned enterprises. We can see that, for example, for households, whether it is one family in Beijing or in Lhasa or in some other underdeveloped region, we pay almost the same price for electricity. But the cost of supplying electricity to different regions differs very much; there is a large difference in cost. However, the price that families pay for these public services is almost the same, because the state-owned enterprises that provide this kind of public service are not profit-oriented; they are service-oriented. So the government plus SOEs make the two forms of equalisation in public services and public infrastructure. That is much more fair for distributing the cake of growth.

Dede Nickerson, Strategic Head at Happy Entertainment; American producer

Hi, I’m not an ambassador. I’m a film and television producer, but I participate in the activities of the China Center for Globalisation. Two quick questions, one for Professor Liu and Professor Huang. When you were talking about the industrial policy for the next Five-Year Plan, you didn’t mention robots or the automation of industry, and how that will displace workers in China. And also, I haven’t read the Five-Year Plan readout yet, but I wanted to ask whether there was any discussion about universal basic income in the next Five-Year Plan, and how that is being addressed as part of what’s going to happen between AI and automation in the industrial sector.

For Professor Wang, I just quickly wanted to get your read on what with the U.S. effectively abandoning climate goals and green energy and green technology. You didn’t really touch on that in your presentation, because that is now the stated policy of the United States, and it hasn’t come up. There are other issues: AI, chips, fentanyl. We all are very aware of the other issues that come up in the bilateral discussion, but this isn’t. And to me, it’s a huge, huge issue. Do you see any effort being made in your area to push the United States to at least acknowledge that climate change is real and the need to develop alternative energy and really work on this issue, because for as somebody who pays a lot of attention to it, it seems as though it’s been abandoned. So I’d be curious to hear in the context of what you were presenting.

Pradeep Kumar Rawat, Ambassador of India to China

For the two professors, in the presentations, there was a lot of emphasis on industrial production. But when one looks at the debate in China, there is a lot of emphasis on consumption. Are there any concrete language or concrete markers in the 15th Five-Year Plan for consumption?

Paulo Jorge Nascimento, Ambassador of Portugal to China

Thank you very much. Just a quick question on the issue of industrial output and the change of its pattern. How do you think it’s going to be compatible with the fact that, at the same time, unemployment rates, apparently, in China, according to certain sources, are growing. And in what terms this industrial production change pattern would imply or have implications in employment and in social stability? Thank you very much.

Marcelo Suarez Salvia, Ambassador of Argentina to China

Thank you very much. Thank you for organising, and thank you for all the presentations made. I would like to know if you could please elaborate further on what would be the external challenges that China has to face and in which way those challenges are tackled or contained in the Five-Year Plan, and also, if there is any indication in the Five-Year Plann that international trade will be more prone on using renminbi as foreign currency in place of the U.S. Dollar. Thank you.

LIU Baocheng

For the artificial intelligence, I’ve been teaching, actually. Some sort of substance in there was that those young guys working in the AI circle don’t work that hard, because you’re going to kick yourself out of that job with AI. But actually, for any sort of industrial revolution or upgrading of tools, they’re going to displace a number of jobs. So that’s very definite.

But that’s not really dangerous, because, as an economist, I never believe in a concept called unemployment, because when the jobs do not need so many people, it means those people deserve some rest, and they deserve better education. They deserve a longer time in the concert hall, in the galleries. So we can talk about four days’ work in a week. Why should we work that hard when the production side can really fulfil people’s existing needs? So that’s not really a big worry of mine.

My worry is that this round of disruptive technology, of artificial intelligence, is different from the previous three rounds, be it machinery, be it mechanical, or bio, etc., because this can really re-engineer your brain. And if some bad guy is sitting on this whole thing, he can really turn out to be a Frankenstein to manipulate people. So that’s why we really need to carefully roll out some of the ethical directions before we rush to the door.

On the other side, we can really bring about more practical applications. Like in my house, we have a robot cleaning the floor. These are really very helpful and practical. Therefore, nobody can really stop the continuous industrialisation and technological advancement. So we have to adapt to it in terms of value, policy, our own behaviour, and also expectations.

And then, as for the consumption, whether we have a consumption index, I think the beauty of the Chinese plan, as it evolves, is that it turned out to be less stringent on specific metrics or specific data. It’s just there to set up a blueprint, and at maximum, a roadmap for different localities and different industries to move along a coordinated direction, instead of specific figures. Because this way, they do not have the incentive to be more adaptive to their local environment and local specialities. Therefore, for consumption, we do not have clear metrics on how to measure for the next Five-Year Plan.

Right now, we have nearly 60% as a driver for Chinese GDP growth. But definitely it’s going to be on the increase, particularly in the high-end service area to deal with those people like me and Professor Wang who are getting older, with those high-end services, medical services, and other information services, etc. So it’s really more market-driven than the government giving specific quantitative figures on how far we can move forward.

And equally for the spending pattern. As we said, while China has a high savings rate, we do not really want to tell people, Okay, you need to reduce your savings rate below 50 or even below 40. I think that’s how China is getting more relaxed on the market performance and the social performance than government-mandatory orders.

And lastly, for the RMB, so far, there have been high expectations, particularly now when some countries are under heavy sanctions over the SWIFT system, etc. They have an outcry to build even a uniform currency within the BRICS system, etc. But so far, in the foreseeable future, this is totally unrealistic. And also for China, in terms of denomination, in terms of settlement, and also in transactions to use RMB, it is still below 5%. Therefore, there’s a long way to go—not really there to blame the world’s existing system, but rather that China has not really liberalised its capital account, and therefore it’s China’s own choice.

If we are able to emancipate the capital account for exchange, we’re definitely going to achieve roughly 18% and even more. But we have other considerations for financial security and to deal with the more abrupt changes. Now the whole world is facing challenges over cryptocurrency and decentralisation, etc. Therefore, I do not think China is now in a rush to go for very rapid RMB internationalisation.

But the positive side is that Chinese big giant banks are spreading their wings across the globe so that they team up with global financial institutions to boost more use of RMB. But it’s all a voluntary choice of the business and individuals, instead of China giving a very tough push for the internationalisation of the Chinese currency. So that’s my observation, please.

HUANG Yanghua

Thank you. Just a short add-up after Professor Liu. So today we are talking a lot about industry, technological innovation. It is not our fault. This is the topic today—the industrial cooperation. And in the next Five-Year Plan, industrial development or technological innovation is only a part of the comprehensive national plan.

So, back to your question. Besides the industrial issue, there is also the demand-side issue. The priority of the demand-side issue for the next five years from the central government is creating enough and high-quality jobs. That is the first priority for demand-side or consumption policy. Without jobs, without income, no consumption.

And the second point of the consumption policy is not about the quantity, it is about the quality. For me I am in the first year of my 40s, and I have no demand for goods, but I want to have a much better quality of life. So this is the trend, because people are upgrading their demand structure. Their willingness to pay is not about quantity, to have more things for the family, but about quality in goods and also in services.

So we also notice that in the next five years, the reform of the vacation system is starting, and people may have more vacation, more holiday days with salary, or they will have a much more flexible system for them to enjoy their vacation. Because compared to the Western partners, the Chinese people have little holiday spans.

We also notice that, in general, for investment, over the last more than 40 years, we invested and focused on materials, on infrastructure. And in this new plan, we notice that the government advocates investing in people. That means they will provide many more opportunities in education, in training systems or vocational training systems, and other kinds of services that focus more on how to make people much more compatible with the progress of technology.

For example, some of the jobs may be replaced by automation, but if artificial intelligence and the government and society are raising some funds or some resources to help these people have their new capability or their new skills to cooperate with this new equipment. So there are a lot of changes because of technology and industrial progress, and some of the policies are following up to deal with this issue. As we know, development always has some issues, and the development is to deal with these issues. So this is my short response. Thank you.

WANG Zhi

On the U.S. climate policies right now. When one government changes, another government’s policy… basically, they terminate all the subsidies for renewable energy right now in the U.S. But, you know, the U.S. has 50 state governments. The U.S. federal government actually does not have the power that the Chinese central government has. Like I’m moving to California—California still commits to the Paris climate goals. We see the fluctuations. We don’t know what the next president will do. So the U.S. is really, right now, uncertain. I’m very careful, you see, because I think the U.S. right now is outside this effort, but some state governments still want to join this effort. I hope this answers your question.

They didn’t lay out a very clear goal of how much consumption will increase, but you will see that the tone of the proposal is centred on humanity. They want the full development of human beings. So that means, you see, for the first time in the Central Committee’s documents, they mentioned changing the vacation patterns. You know, right now, when we have big vacations, like the national holiday, all the tourist places have too many people, and the quality is really low. So this is really no cost—it’s an operational research problem: try to arrange people at different times to go on vacation. That can boost the local service industries.

The AI will save us time. Basically we can go on a four-and-a-half-day work week or a four-day work week. So you see, in Europe, there’s no decline in productivity. I think China will follow someday. Thank you. Thank you.