Transcript: CCG and UNICEF China convene VIP Luncheon on children

Amakobe Sande, Tang Min, and Gordon G. Liu explore inclusive, resilient development and investing in the next generation.

On 4 December, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), in partnership with UNICEF China, convened the 20th CCG VIP Luncheon in Beijing under the theme “Investing in the Next Generation: Forging Global Collaboration for Inclusive and Resilient Development.”

The luncheon featured keynotes from:

Amakobe Sande, UNICEF Representative to China

Tang Min, Executive Vice Chairman of the YouChange China Social Entrepreneur Foundation, Vice Chairman of CCG, and former Counsellor of the China State Council

Gordon G. Liu, BOYA Distinguished Professor of Economics, Dean of the Institute for Global Health and Development, Peking University

The open discussion session also drew contributions from Bernard Shwartländer, Co-Chair of the Governing Board and Distinguished Research Professor of Global Health, Peking University Institute for Global Health and Development; Former Global Health Envoy of Germany

Ambassadors in attendance included Hannes Hanso, Ambassador of Estonia to China; Robert Lee, Ambassador of Fiji to China; Thorir Ibsen, Ambassador of Iceland to China; and Karlis Eihenbaums, Ambassador of Latvia to China, alongside representatives from other diplomatic missions in Beijing, former Chinese diplomats, international organisations, academia, and the business community.

The video recording of this luncheon has been made available on CCG’s official YouTube channel and WeChat blog.

The following transcript is based on the video recording and has not been reviewed by any of the speakers.

Mabel Lu Miao, Co-Founder and Secretary General of CCG

Your Excellencies, Ambassadors, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, dear Ama, dear Henry, dear all. It is my great pleasure to welcome you all to the 20th CCG VIP luncheon. Thank you for taking the time to join us today, the 20th already, how time flies.

The CCG VIP Luncheon Series, initiated and hosted by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), has become an important platform for dialogue and exchange. It brings together diplomats, international organisations, leading enterprises, and academic experts to share insights on China’s development and to foster mutual understanding and cooperation in an increasingly interconnected world, including in the area of global governance as well. This time, we are co-hosting with UNICEF China to conduct this event.

Today’s luncheon is particularly timely, as it focuses on investing in the next generation and forging a new global framework for inclusive and resilient development. As the world enters a period of profound transformation, marked by rising inequality, intensifying climate pressures, complex geopolitical dynamics, and rapid demographic shifts, these converging global challenges are redefining development trajectories across nations. In this context, early childhood development, particularly during the critical 0–3-year window, has increasingly emerged as a decisive foundation for long-term societal resilience and inclusive growth.

At this historic juncture, a number of pressing questions call for comprehensive and in-depth discussions. To explore these essential questions, CCG, together with UNICEF China, is convening the 20th CCG VIP luncheon, bringing together leading representatives from international organisations, government ministries, the private sector, academia, and the diplomatic community.

I would like to extend a special welcome to our distinguished guests. We are privileged to have diplomatic representatives from 19 countries, including four ambassadors, with us today. Specifically, we have invited the Ambassador of Estonia, the Ambassador of Fiji, the Ambassador of Iceland, and the Ambassador of Latvia to join us.

In addition, we have diplomatic representatives from the Embassy of Argentina, the Embassy of Brazil, the Embassy of Canada, the Embassy of Croatia, the EU Delegation, the Embassy of Indonesia, the Embassy of Italy, the Embassy of Malta, the Embassy of the Netherlands, the Embassy of Pakistan, the Embassy of Portugal, the Embassy of Türkiye, the Embassy of the UAE, and the Embassy of Vietnam also participating in our event. Welcome to you all.

We are also honoured to welcome the representative from the Asian Development Bank to join us today. Moreover, we are privileged to be joined by government officials and academic experts from different institutions as well.

Furthermore, today’s luncheon features participation from leading companies, including from Brazil, Embraer, and Catching Shadows. Last but not least, the presence of media representatives from outlets including CCTV, China Daily, and Xinhua News Agency will help ensure the dissemination of today’s important discussions.

Thank you all once again for your support and engagement. We look forward to a fruitful and inspiring luncheon.

Now, without further ado, let us begin with our opening remarks from Dr Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of the Center for China and Globalization and also a former Counsellor of the State Council of China. Welcome, Dr Wang.

Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of the Center for China and Globalization (CCG); Former Counselor of the China State Council

Thank you, Dr Miao. Dear Amakobe, colleagues from UNICEF, Your Excellencies, Professor Tang Min, Professor Liu Guoen, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, it is really a great honour.

We are gathered here again for the 20th, which means that in the last 20 months, every month we have held a CCG VIP luncheon. Today’s CCG VIP luncheon is held in partnership with UNICEF, the largest UN operation in China. We are honoured to have with us the UNICEF Representative to China, Ms Amakobe Sande, as well as other UNICEF colleagues.

It is really a great honour that, apart from the geopolitical and other hot issues that we have been talking about, today we would like to bring some practical, down-to-earth and, in fact, more important issues to the table, namely investing in the next generation for a resilient future. That is really what we are going to talk about today – a very important subject.

So it is really a distinct honour to welcome all of you to this 20th VIP luncheon. Today, not only because we have so many issues to discuss, but also because we want to shift our gaze from immediate geopolitical shifts to a long-term horizon, which is to pin the future on the next generation, forging global collaboration for inclusive and resilient development.

At this historic juncture, I think it is so important to talk about this future generation with us in the global sense, and also with UNICEF, with its vast knowledge and activities. It is really the best occasion to talk about that.

First of all, let me just highlight a little bit of China’s milestone achievements in child development. We cannot discuss the future of global child development without looking at China’s progress. According to the latest data from 2024, China has delivered a remarkable scorecard that reflects a historic leap in both health and education.

China’s infant and under-five mortality rates have been greatly reduced to historically low levels, and these figures firmly place China among the world’s advanced upper-middle-income nations. So you can see China has done very well, not just in lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but also, in terms of children and infants, China has done very well in achieving high standards.

Simultaneously, China has made great strides in educational equality. In 2024, the gross enrollment ratio in preschool education reached 92%, which is very high, while coverage of inclusive kindergartens reached 91.61%. That is also very important. The Chinese government is giving a lot of support to kindergarten education in China. These figures represent a massive step towards universal access.

However, as China faces demographic shifts and an ageing population, how to really encourage more births and promote population growth is still a challenging issue. So our challenge now moves from coverage to quality, particularly in prioritising the critical 0–3 age window, to ensure every child has a fair start. These are just some highlights.

The second point I want to mention is UNICEF. It is really a great and steadfast partner in China’s journey in bringing up children, in health, in education, and in all related activities. I would like to pay special tribute to UNICEF. For decades, UNICEF has been more than a donor; it has been a trusted partner and a pioneer in innovation, bringing many ideas and much practice.

From assisting China in building a vast network of child directors to support vulnerable children to introducing the scientific concept of early childhood development to rural areas, UNICEF’s work has helped to bridge the last mile of social services. We deeply appreciate the leadership of Ms Amakobe Sande and her team, not only for advocating these issues, but also for turning policy into tangible action on the ground. This is really appreciated, and we thank UNICEF very much for its leadership in this aspect in China.

Finally, I just want to say that as we look to the post-2030 agenda, and also to the next 15th Five-Year Plan of China, we are facing a world of accelerating climate change, technological disruption and uncertainty on many fronts. Investing in children is our most effective strategy to build long-term societal resilience.

So today we are really privileged to be joined by three top experts, particularly Madam Amakobe. I would like to invite you to give us a keynote, to be followed by our two distinguished professors, Professor Tang Min and Professor Liu Guoen.

We really appreciate that these exchanges among our luncheon guests are going to be very interesting, stimulating and enlightening, to hear how China looks at, and how UNICEF looks at, children’s development and related development for the future, which concerns the most important, brightest and youngest part of the future that we really have to cultivate and look after.

So without further ado, let me introduce our next speaker, the keynote speaker, Ms Amakobe Sande. She is the UNICEF Representative to China. Ms Sande provides leadership and strategic direction for UNICEF and liaises with the Government of China. She also looks after the UNICEF–Government of China country programme, delivering results for children. She brings to this role 30 years of experience and expertise in international development, humanitarian coordination, policy analysis, advocacy, resource mobilisation and partnership.

Prior to joining UNICEF, she was the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in Eritrea, coordinating 21 agencies in supporting the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals—a very rich experience. Madam Sande also led UNAIDS as Country Director in Beijing, as well as in Uganda, Malawi and Lesotho.

Before joining the UN, she worked in renowned international organisations such as Oxfam and ActionAid International, where she served as Deputy Country Director in post-genocide Rwanda, Country Representative in Zambia, Regional Programme Manager for the Middle East, Eastern Europe and the former Caucasus – countries like Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan – and in the same function covering the Southern Africa region.

Just prior to joining the United Nations, Ms Sande was the Director for ActionAid International’s Southern Africa Partnership Programme. So she has vast experience. I also remember that during COVID, Ms Sande was actually the acting UN Coordinator in China, and she came to a CCG event when we launched the Global Young Leaders Dialogue and spoke on behalf of the UN agencies in China – very supportive.

Ms Sande has also served on a number of boards and advisory committees, including the Global Campaign for Microbicides, the African Public Health Network, the Southern Africa AIDS Information Service, and the China AIDS Fund for non-governmental organisations.

So many impressive social posts. Ms Sande received a master’s degree in Development Studies from the Australian National University in Canberra, and also a bachelor’s degree in International Relations from the United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya.

So, without further ado, let’s welcome Ms Sande to give us a keynote.

Amakobe Sande, UNICEF Representative to China

Good afternoon, and it’s such a pleasure to be here. There’s something special about the 20th, the number 20, and being able to partner with my dear friends, Dr Henry and Dr Mabel. Let me also recognise Their Excellencies in the room today, as well as friends of both CCG and UNICEF, as well as my co-speakers this afternoon, Mr Tang Min and Professor Liu Guoen. It is so humbling to see the participation at the luncheon today. Thank you for making the time.

So, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, we meet at a moment of profound transformation: economies shifting under technological disruption, societies grappling with demographic change, and the global system strained by inequality and geopolitical tension. And in this context, one question, I think, rises above all others: how should we—how should the world—invest in the next generation? And this is not just a matter of sentiment; it is a matter of strategy, it is a matter of economics, and it is also a matter of survival.

And Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, the science is clear: there is no period in human development as powerful as the first thousand days of life. In these early years, the brain forms more than one million neural connections every second, building the architecture for cognition, for emotional regulation, for creativity and, indeed, for resilience. It starts there.

Beyond the science, the economics of investing in the early years was established, and clearly so, by the Nobel laureate James Heckman. He found through his studies that every dollar invested in early childhood yields a return of about 7 to 13 dollars in economic benefits in the long term—more than at any other stage of development in the human life cycle.

The Lancet Commission on Early Childhood Development went even further and informed us that children who receive nurturing care, nutrition, health, responsive caregiving, and early learning enter school more ready, they earn more as adults, and contribute more to society.

And so, really, the conclusion is simple: the earliest years are not preparation for life, they are life. And if we fail then, we fail the next generation. We fail future generations.

Let me also talk about a second window of opportunity that is equally powerful and most often misunderstood: adolescence. Biologically, adolescence is the second moment of neuroplasticity, synaptic pruning, identity formation, and also social cognition. Economically, it is the conversion point where potential becomes productivity, and this is when societies transform early investment into innovation, enterprise, and leadership.

And let me just cite a few examples to show how we are missing that window of second opportunity. Globally, we have a learning crisis, defined by the World Bank and UNESCO in their tracking of SDG 4 on education as “learning poverty.” The term “learning poverty” is an interesting one. It combines two indicators: schooling deprivation and learning deprivation, into a single measure that looks at the ability to read and understand a simple text by the age of 10. Many of you have 10-year-olds.

Before COVID-19, learning poverty affected 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries. That figure, after the pandemic and related disruptions, rose to 70%. In other words, 70% of children by the age of 10 cannot read or understand a basic text. This now affects 250 million children, 100 million of them in Africa.

Furthermore, today, nearly one billion adolescents lack access to skills aligned with global labour markets. Many more see a worrying disconnect between what they learn and what their future actually demands.

And so, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, the stakes are high. If childhood builds the foundation, adolescence builds the architecture of society. A young person with access to digital training, vocational skills or entrepreneurship pathways contributes to the nation’s competitiveness. A young person without those tools, conversely, becomes trapped in cycles of exclusion and then in informal work or all kinds of instability.

We have less than five years left to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and the truth is sobering: 250 million children under the age of five are at risk of not reaching their full developmental potential. When children are viewed as national assets rather than just mere beneficiaries, societies become more prosperous, more cohesive, and more resilient.

And so we must move beyond the old dichotomy of social policy versus economic policy. We must treat human development in the same way we treat, for example, infrastructure development. When we build a highway, we expect returns over 30 years; when we invest in the mind of a child, the returns can last up to 70 years.

And so a coherent new framework should incorporate perhaps four pillars. The first must be universal foundations in early childhood, consisting of health, nutrition, early learning, and parental support. The second: quality education systems that equip students for the future and do not reproduce inequalities, from preschool to secondary school.

Third, we need to create adolescence-to-employment pathways, including through TVETs, apprenticeships, mentoring programmes, and digital and entrepreneurial skills—the skills for the future. And finally, we must have social protection systems that are enabling. They should include child benefits, parental leave, as well as access for migrant families, and we should not forget disability services as well.

China has demonstrated the power of strategic human capital development. It has lifted more than 800 million people out of poverty and built the world’s largest industrial system. And in doing that, over the past 40 or so years, it has made remarkable achievements in child survival and development. And, in the development of its young people, Dr Henry gave you the statistics; I won’t go into them again. And it did this with clear sequencing, with long-term thinking, pragmatic investments, and by prioritising human capital development as a foundational element of its economic strategy.

Today, China faces a different challenge: an ageing population, declining birth rates, and a rising cost of care. It is now investing in emerging areas which some see as social spending, but really they are about future labour policy, future productivity, and future competitiveness, as well as resilience.

Consider with me the priority investments that are already emerging here in China: expanding childcare services; expanding access to high-quality preschool education; introducing a nationwide universal child grant; addressing the hukou—China’s household registration system—and related barriers, for better integrating the children of migrant workers; expanding investments in STEM education; and nurturing innovation capacity and youth employability to prepare young people for the future economy amidst demographic pressures.

These are not isolated reforms, ladies and gentlemen. These are macroeconomic levers. There are, of course, a few challenges—again, Dr Henry spoke about them—around uneven access and quality, particularly between rural and urban areas. And we should indicate, of course, that rapid development and technological advancement have taken place at a cost to children, at a cost to families. And so new challenges have emerged with that as well.

But there is a story to tell, and it is one of political will. It is one of human capital prioritisation. It is one of robust implementation and monitoring, as well as innovation and achieving scale, and doing so at speed.

China’s opportunity is not only domestic; it is global. And UNICEF is working with China to share the lessons that have been learnt here through South–South and triangular cooperation. Let me give you a few quick examples. With China, we are working to support early childhood development programmes in Africa. With China, we are looking to expand public digital learning platforms—an initiative with the Ministry of Education to promote high-quality, inclusive national digital learning platforms for children in Africa. With China, we are expanding access and quality of maternal and child health services across Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, and setting up centres of excellence; there is one just about to go up in Ethiopia. With China, we are supporting technical and vocational education and mentoring linked to real labour markets. This includes funding, particularly from the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), as well as practical, quality-assured, by-UNICEF technical exchanges and peer-to-peer learning that is rooted in results.

China is also keen to learn from others; it is a two-way exchange. UNICEF has facilitated exchange visits for senior Chinese officials with several OECD countries and other developing countries as well, on issues such as inclusive education, supporting children with disabilities, addressing common challenges around online safety for children, and the opportunities and challenges of rapid AI development; on areas such as social and emotional learning, but also strengthening justice systems so that they are truly protecting children and acting in the best interests of the child.

Allow me to recognise the excellent support of the Embassy of Estonia, which worked with UNICEF to support a senior Chinese delegation to go and learn about their early childhood practices. Similarly, with the support of the Embassy of Iceland—and again, Your Excellency, you are here—we worked together with experts from Iceland and shared Iceland’s experience on justice in the child protection sector. Again, thank you, Your Excellency.

Similar exchanges have been organised with France, Switzerland, Mexico, Costa Rica, Belgium, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Finland, Norway, Estonia, Spain, Italy, Croatia, South Africa—and the list goes on and on. This is the global opportunity I was speaking about.

Let me speak without euphemism: a nation that fails to invest in children is not saving money; it is choosing to pay a far greater cost—a cost in lost potential, reduced economic growth, and increased social burden. The logic is as elegant as it is uncompromising: invest early, invest consistently, invest in capability, invest with future purpose.

Leaders, ladies and gentlemen, are not remembered for managing the present; they are remembered for shaping the future. And so we stand at a crossroads. One path leads to ageing societies, a shrinking labour force, and widening inequality; the other leads to sustained productivity, shared prosperity and, with that, resilient communities.

We know what works. The science is clear. The economics is compelling. So let us build a world where investment in children is recognised not as mere compassion, but as a strategy and as the defining infrastructure of the century ahead.

I thank you.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you, Madam Sande, for your extensive, comprehensive, very informative, and enlightening keynote. It is really important that you highlight the importance of investing in the next generation, and also that you underline the many challenges, opportunities, and benefits that we are going to see for the next generation.

I particularly liked what you said in relation to China, especially about migrant children. I see we have about 300 million migrants in the cities, and their children should have equal access. This is something I think China still needs to improve. I see a lot of schools closing down because fewer children are being born, and yet many rural children living in the cities still cannot access these schools. So that is something where the hukou system should really be reformed, or even abolished as soon as possible, to make more progress.

So again, a lot of progress has been made, a lot of experience has been gained, and I also want to thank all those countries that have contributed to this great process.

Now I’d like to introduce our next speaker, Professor Tang Min. Tang Min is an old friend of mine for 20 or 30 years, I think at least. Tang Min is also a Vice President of CCG, but he has many other important roles. He was in the 1978 class and graduated in 1982, and then went to study at the University of Minnesota and at Urbana-Champaign in 1984, so he was one of the very early “sea turtles.” He obtained his PhD degree in 1989.

He also joined the Asian Development Bank (ADB)—we have an ADB representative here today as well—where he was in charge of East Asian economic affairs and regional economic cooperation, making many contributions there. In 2000, he was appointed Chief Economist and head of the ADB Resident Mission in China, a very important role.

He later became Deputy Secretary-General of the China Development Research Foundation under the Development Research Centre of the State Council in 2007. Since December 2010, he has served as Executive Vice Chairman of China’s Social Entrepreneur Foundation and also as President of the YouChange New Philanthropy University. So he has played a very important role.

More than that, Tang Min and I were colleagues at the Counsellor’s Office of the State Council, and he is also a former Counsellor of the State Council. I think Tang Min has done a lot of work when he was leading the YouChange Foundation, including many activities in children’s education, e-learning and many other areas. I saw his footprints everywhere.

So I’d like to invite Dr Tang Min to give his speech. Please, let’s welcome him.

Tang Min, Executive Vice Chairman of the YouChange China Social Entrepreneur Foundation; Vice Chaiman of CCG; Former Counsellor of the China State Council

Thank you, Henry, and distinguished guests, and a lot of my friends here. Today I was given an assignment. The assignment is to talk about early childhood development, particularly to talk about the policies and the involvement of civil society. We will discuss three points. First, we will discuss the status: what is the current status for early childhood development? Second, let’s see what the new government policies are. And thirdly, what’s the contribution made by civil society?

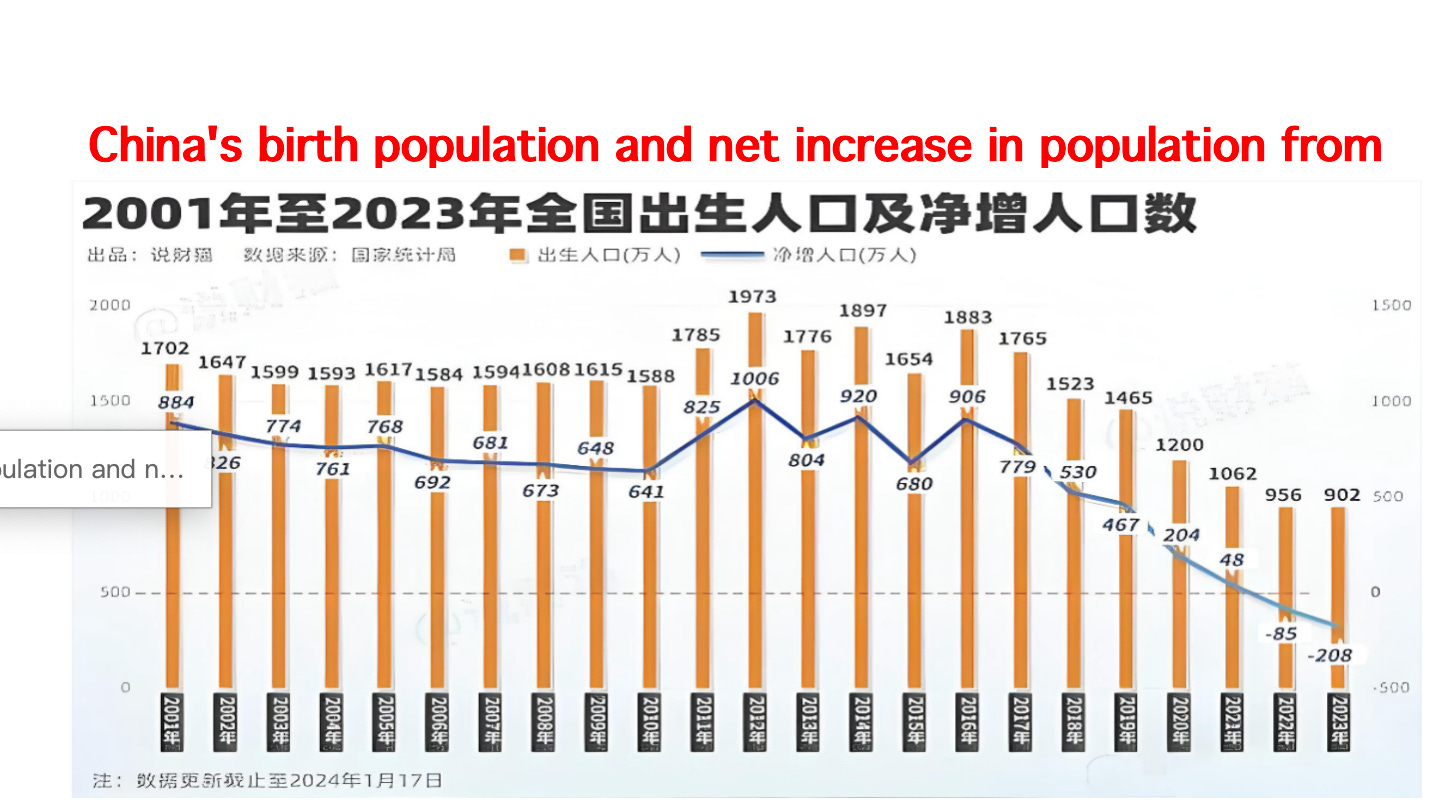

Currently, one of the biggest problems in China’s economy and society is the quickly and sharply declining birth rate. If you take a look at the data, up to 2016, China had about 18 million newborn children every year. But now it has been reduced by half, about 8 million. Reduced from 16 million to 8 million in less than 10 years, so reduced by half. And every year, people also die, right? Newborns minus people who die means that, in fact, starting from 2022, China’s population has begun reducing. Now every year, China’s population is reducing.

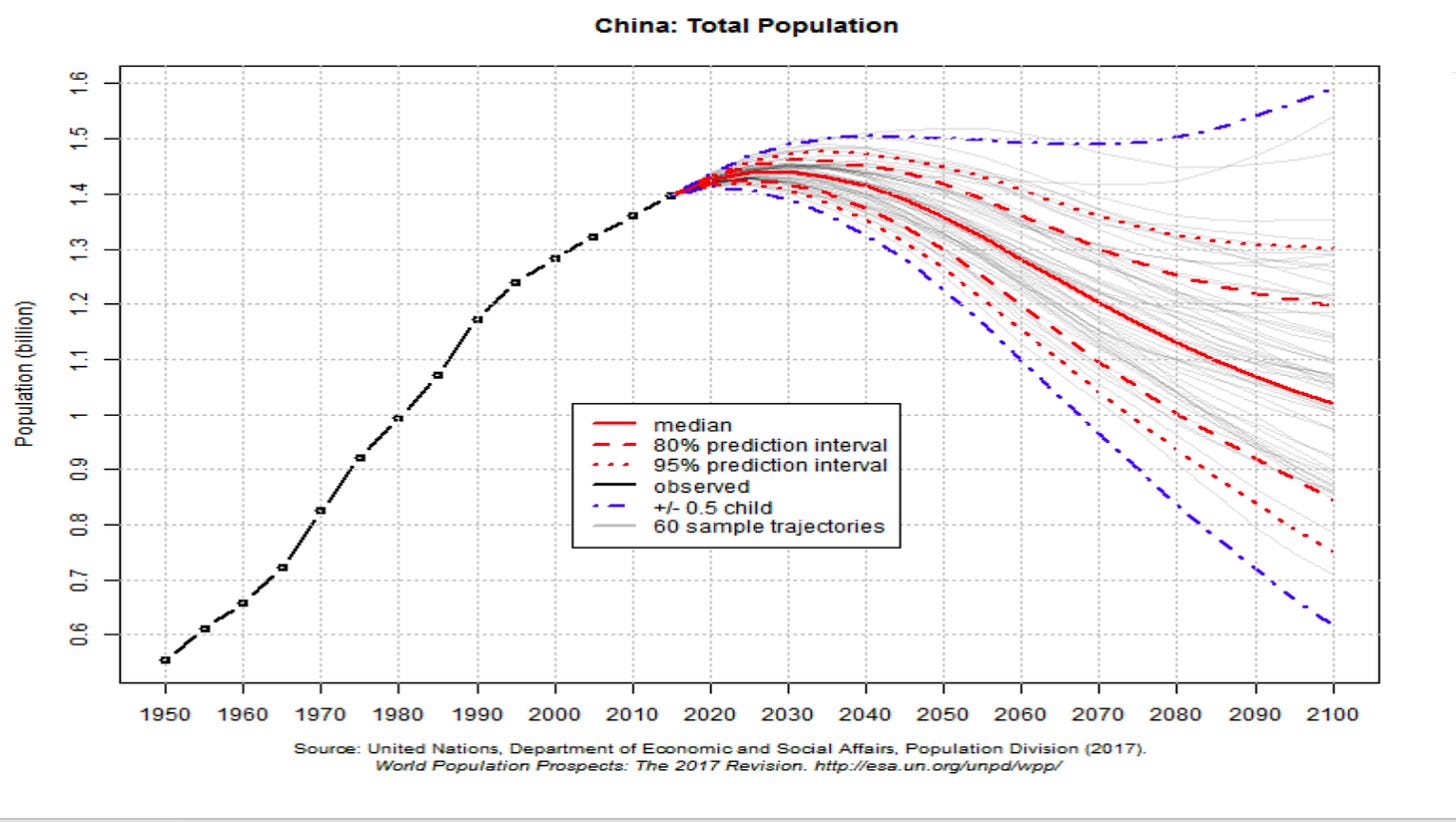

People are doing long-term projections. You can see that we are here, but depending on different scenarios, in the worst scenario, by 2100, China would only have 600 to 700 million people. And even in the medium scenario, we would be around 1 billion in population. So, really, a sharp reduction in the population.

Why are people worried about a reduced population? If we recall China’s history, in the 1960s, China only had about 700 million population. In those days, we started to worry, so we started birth control. In the 1960s, we had only 700 million people. When we had 1 billion people in the early 1980s, we applied the one-child policy, and a very strict one. Now we have 1.4 billion people, and we worry that we do not have enough population. It looks a bit controversial, right?

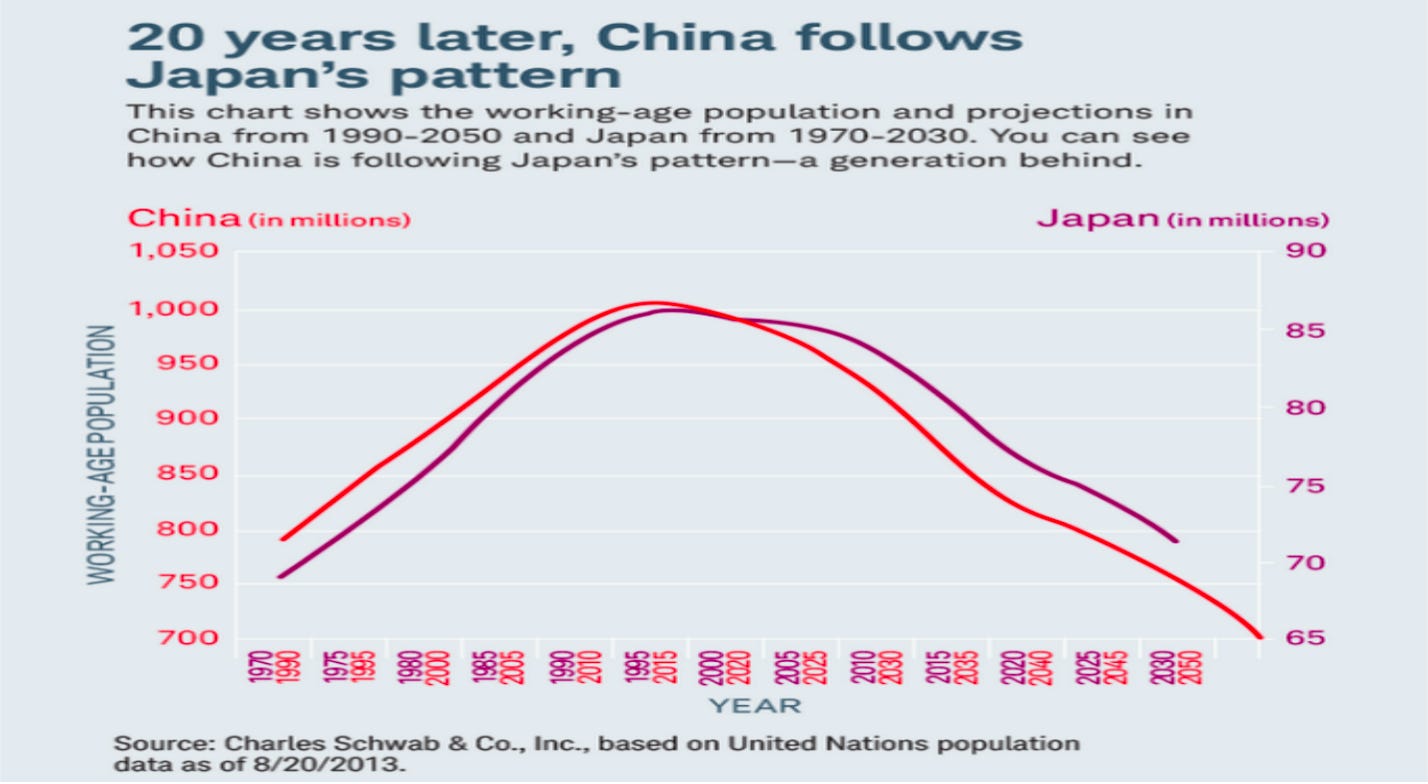

But why do people worry about the population reduction? Because we watched what happened in Japan. If you take a look, this is Japan’s population growth and then reduction. And the other one is China, just 20 years behind. Most likely, we will follow Japan’s pattern in terms of population, and our population will also sharply reduce, just 20 years behind.

But why so much worry about Japan? If you take a look at the next chart, economic growth, Japan’s economic growth was very high before up to the 1990s. Then the growth rate sharply reduced to around 2% every year, and in many years, even less than 2%.

Why? Several reasons. Because of the real estate bubble and all sorts of things. But one of the key areas which caused the current problems is the demographic situation: the reducing population. So people worry that maybe we will face a similar problem. These points are being debated among economists locally. Some people say that they worry that we will follow the same path as Japan’s growth. The other group says, Don’t worry, we have AI now, and we have robots. Nowadays, 50% of robots are used in China. And we have this new thing called an AI agent. Its impact on job opportunities may be even more than robots, because that will replace many white-collar jobs. So we are worried that in the future we may not have enough jobs for young people. So if the population reduces, maybe that is a good thing. That is what people are debating.

The main problem is that we have to have a good income distribution system. Even older people can consume if they have enough income. So that’s another issue. But in any case, population has become one of the major factors impacting China’s future growth.

Okay, nothing we do now can change this trend. The government has started doing the right things. A few years ago, we stopped the one-child policy, and now we even give subsidies to families that have children. So everything is changing. But from global experience, from the direct experience of developed countries, you can slow the trend of population reduction a little bit, but you can not change it.

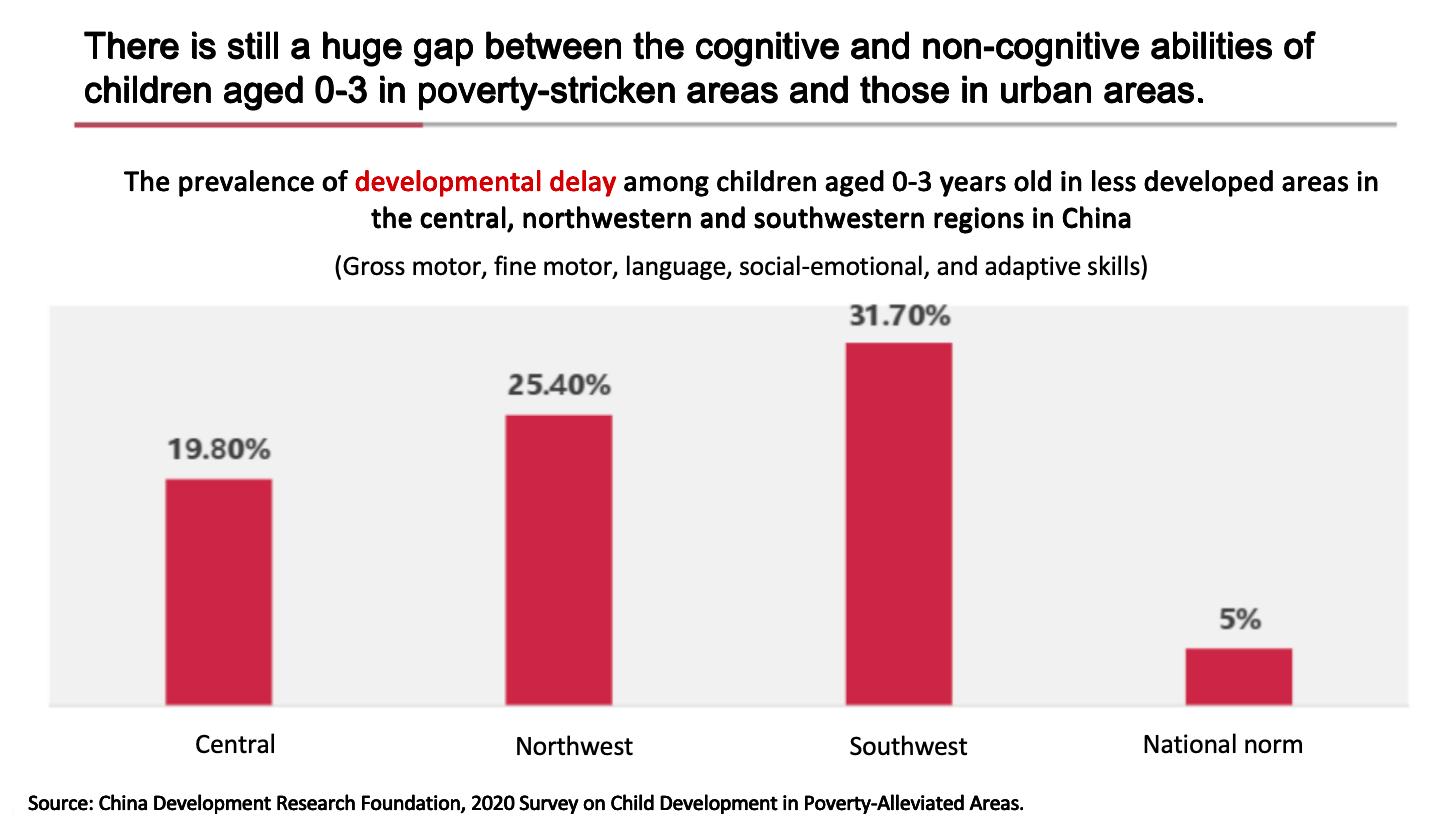

Then we talk about children. We have fewer children, but if children are better educated, better supported, and have a better life, it’s not bad, right? But every year, the number of children is reducing, and about 40% of those kids live in rural areas. The main concern in urban areas is more or less manageable, because parents in cities pay a lot of attention. But in rural areas, there is a problem. So problems we worry about in early childhood are mainly in rural areas.

There are significant gaps. As Henry mentioned, on average, China’s education, childcare, and all these things look good in terms of national numbers. But the difference between urban and rural is big, not only for kindergartens or teachers, but also for resources, hardware, and everything is quite different.

If you take a look at some of the data, it shows the proportion of families in difficult situations in raising and educating their children. Nationwide, no problem, but for families in poverty areas, or families that used to be poor, there is still a very high proportion of children with problems.

If you look at developmental delays among children, nationwide, it is about 5%. But you can see in central areas, poverty areas, and in the southwest areas, it is much higher than the national average. So this is a problem China has to address.

I fully agree with Madam Sande. She gave many policy recommendations. I think they should be applied, particularly to rural areas in western regions and to those poverty areas.

So the government is starting to be concerned about the declining population and also the gap between locations, with children in different places getting different treatment. The government will have many new policies. One of the main policies, as we know, is a core policy mainly to subsidise and support families that should have more children, and the government will support them.

Starting this year, every family nationwide, if you have kids, you get 300 yuan per month, 3,600 yuan per year. This is just the beginning. Maybe in the future we will have more to encourage people to have more children. This 3,600 yuan is not a big deal, particularly in urban areas, but it does play an important role in rural areas. Aside from that, the government also put more money and more resources into improving conditions in rural areas, kindergartens, early childcare centres, and so on, making efforts to reduce the gap.

In the meantime, civil society also plays a very important role. Let’s see what civil society contributes. Now, what we do is try to fill the gap between government services, especially focusing on rural and underdeveloped areas, as a civil society effort, starting from the very beginning by doing piloting.

I recall about 15 to 20 years ago, when I was working in China with many agencies, we were doing pilot work and doing “teaching for work” projects. In those days, we did not have enough kindergartens, so we hired some teachers who would move around instead of having one big kindergarten. One teacher could take care of four or five villages, that kind of thing. Nowadays, there are more activities.

Let me show some cases. One is the China Development Research Foundation, which is a leading agency in this area. I used to be a Deputy Secretary-General there 10 years ago, and they are working on many new projects. Next.

One project is called the China REACH Program. The China REACH Program means China Rural Education and Child Health Program. What we do is hire some people as experts, and every week they have to visit rural families to give suggestions and training to parents, mainly mothers, on how to take care of young children. We have training programmes; we hire many young people, train them, and they go to those families every week, spending one or two hours to have discussions and give suggestions—that kind of activity.

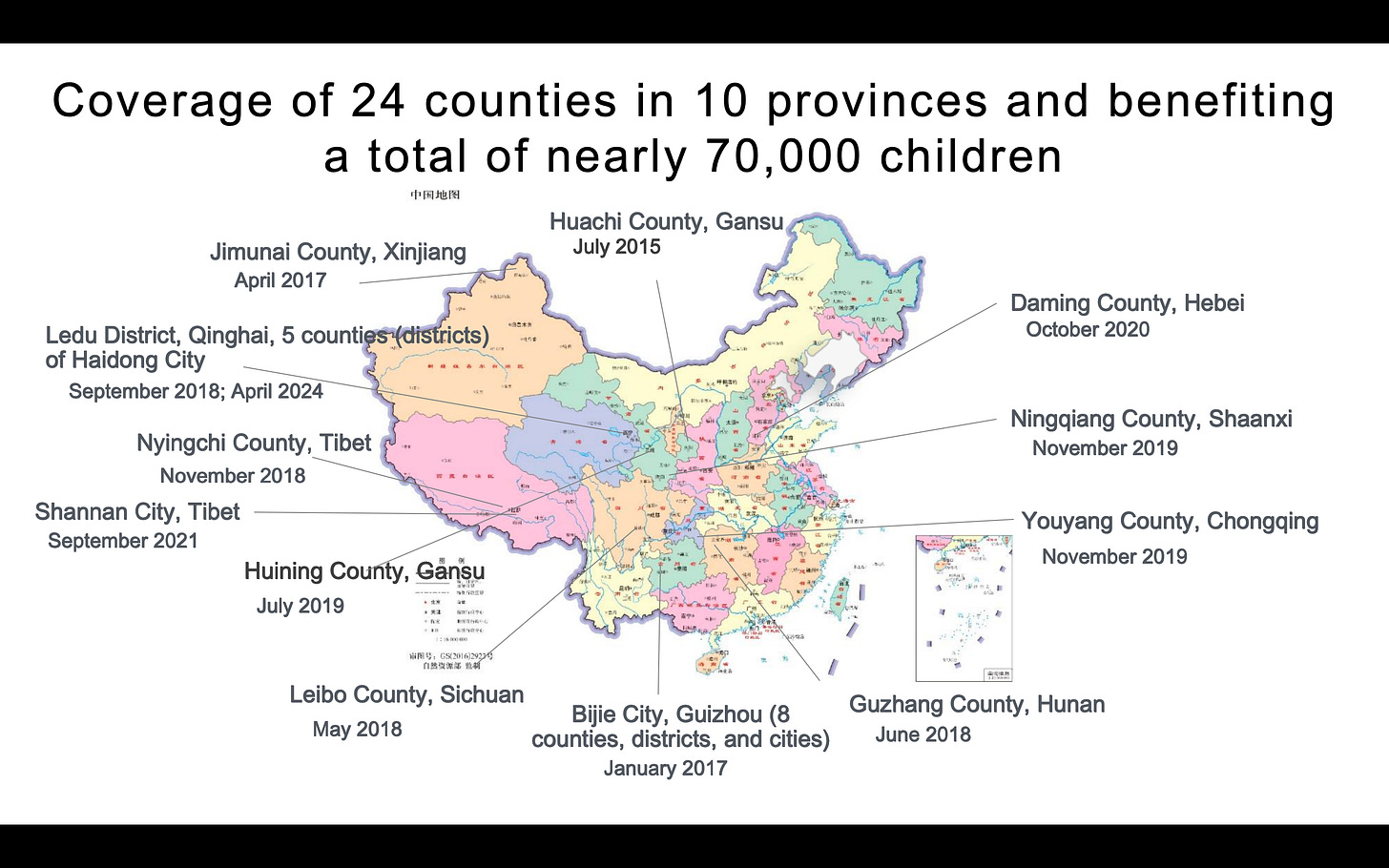

Currently, we are running this in 24 counties in 10 provinces, mainly in poverty areas. Now it covers about 70,000 kids or families, and all those activities are moving around. In terms of contributions, we would like to expand. Many scholars, including myself, donate some money every month to support this programme.

So this is in poverty areas, where all sorts of home visitors go to help parents and give them new skills. Some foreigners are also getting involved, and they really appreciate and are very happy about this programme.

This is for tight-knit family home visits. These teachers are called home visitors, and all these things bring benefits through this programme. Now we would like to expand this programme. So far, it is still a pilot. We want to show the government and the public that this kind of intervention is quite effective and can really address the problems in rural areas.

Also, there is another foundation which I am directly involved in: YouChange China Social Entrepreneur Foundation. We mainly train young teachers. We call the Green Pepper Program—a young teacher support programme, in cooperation with many agencies. So far, we have been running it for 20 years and have trained 20,000 teachers. Among them, about 5,000 are kindergarten teachers. We improve their skills through internet-based, whole-year training, one hour every day, and we invite the best trainers in the country to give them training so that they improve their skills.

This is one area in Guizhou.

These are the children whose teachers are receiving training and getting better programmes for their kindergartens.

Another case is the “Raising the Future” project. This is run by the Magic Bean Public Welfare Foundation, another foundation doing a very similar programme, mainly addressing children aged 0 to 3 and giving training.

The project provides systematic training and teaches teachers how to really address the needs of 0 to 3-year-old children. It provides a lot of support. In those areas, China’s kindergartens usually cover ages about 3 or 4 to 6, but for 0 to 3, it is still not very popular. So this is a special programme to help very young children.

This project is getting a lot of outcomes. So far, 90% of rural families there are covered, and many receive weekly training, and so on. It is getting awards and global acknowledgement, receiving awards from many organisations. So this programme really helps. It is still not a very large-scale programme, but because it is successful, it is getting attention from the government and from enterprises that want to do ESG work. They want to support it. So gradually it will become a bigger programme.

In this sense, China’s early childhood situation will change dramatically. The government is trying to do many programmes. The main efforts are probably in rural areas, particularly in those that are poverty areas or used to be poverty areas. And these efforts have to be made not only by the government, but also by civil society, NGOs, enterprises, and international organisations like UNICEF. We need a lot of new concepts and more resources. Hopefully, when the population is reduced, teachers can focus more on the quality of education. When the population is reduced, there are many negative impacts; the good side is that we have more resources to put into each child. Hopefully, we can make these important rural areas match what’s happened in urban areas. And hopefully, after many years, the situation will improve. Thank you very much.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Great, excellent, Dr Tang. It was really a very fascinating highlight of the general demographic situation in China and what the challenges and opportunities are. You also used vivid examples and case studies, for example, your work in these areas, so that is really great.

So thank you again, Dr Tang, for your great sharing and also for your practical work in this field, too. Congratulations again, and thank you.

Now I’d like to introduce our next speaker, Dr Liu Guoen. Professor Liu is a Peking University Boya Distinguished Professor of Economics, and he is also the Dean of the Peking University Institute for Global Health and Development and a fellow of the Chinese Academy of Medicine. So he is very hands-on and has worked in many areas in this field.

Professor Liu also serves as Director of the Peking University China Centre for Health Economic Research and Chair of the Academic Committee of the Peking University Institute of Educational Economics. He also holds many distinguished roles in public service, including co-organising the U.S.–China Track II Dialogue on Health, and you have your great friend Peter sitting beside you there.

He is a Health Reform Advisor to the State Council, a member of the Health Reform Commission, and an Associate Editor for the SCI academic journals Value in Health, Health Economics, and China Economic Quarterly, so you have many academic editorial roles there as well, and he is also Editor-in-Chief of the China Journal for Pharmaceutical Economics—quite a few responsibilities.

Professor Liu obtained his PhD in Economics in 1991 from the Graduate Centre of the City University of New York, under the supervision of Professor Michael Grossman, so very well trained. He also completed his post-doctoral training in health economics at Harvard University under the supervision of Professor William Hsiao.

I’m not going to go into detail about all those great supervisors, but again, I know Professor Liu is a great expert in health, including issues related to children, and in general, he is one of the top experts in China on health development, health education, and health policy recommendations.

So without further ado, I’d like to invite Guoen to give his speech for this important VIP luncheon. Thank you. Let’s welcome him.

Gordon G. Liu, BOYA Distinguished Professor of Economics, Dean of Institute for Global Health and Development, Peking University

Thank you, Henry and Madam Sande, for inviting me to join this great luncheon event. I have to admit that I like this topic quite a lot: investing in future generations. When we talk about investing in future generations, it’s easy to frame it as a more moral choice. But today, I want to challenge that narrative. Investing in future generations is not a choice at all; it is a survival imperative for Homo sapiens. The decisions we make right now—how we value resources, how we shape our economies, and how we respect planetary limits—will determine whether tomorrow’s generations inherit a world that can sustain human life.

Over the past few years, as we have all grappled with climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource scarcity, it has become increasingly clear that our current path is unsustainable. But despair isn’t a choice or option. Instead, we need a clear, actionable framework to guide our choices.

Today I want to share four pillars that tie our present actions to humanity’s long-term continuity, and especially introduce an innovative tool that may help turn these pillars into measurable progress. I have not prepared slides for you about what I will introduce to you, but I do have a nine-minute video clip that can be played later after my speech, if time permits.

Pillar 1. Who are the future generations? They are not abstract strangers, nor someone else’s children, and certainly not a distant concept we can afford to ignore. Future generations are the continuity of Homo sapiens, Period.

Think about it. Every innovation we celebrate, every tradition we cherish, every scientific breakthrough we build on is a gift from those who came before us. They invested in education, in infrastructure, in knowledge, so that we could thrive.

Now it’s our turn to pay that forward. Investing in future generations isn’t about sacrificing for others; it’s about preserving the legacy that defines us as humans. To neglect their needs is to erode the very idea of ourselves extended through time.

This isn’t just a philosophical point; it’s a practical one. The choices we make today, whether to exploit a non-renewable resource or protect it, whether to prioritise short-term growth or long-term sustainability, will shape the world our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren inhabit. And make no mistake, their fate is our fate. The survival of Homo sapiens depends on our ability to see beyond the next year, the next decade, and indeed far beyond our own lifetimes.

The second pillar of investing in future generations is protecting our non-renewable assets, including fossil fuels, minerals, freshwater, and other resources that cannot be replenished on human time scales. In our current economic system, these assets are often discounted for future use. I’m an economist by training. We start our first class in teaching us how to discount the value of assets for future use.

We extract them at record rates, burn them for energy, and discard them without a second thought because they are cheap, convenient, and profitable in the short term. But this approach comes with a great opportunity cost. We are depleting the resource base that future generations need to survive and thrive on.

Imagine if your grandparents had spent your entire inheritance on luxury goods, leaving you with nothing. That’s exactly what we are doing to future generations when we over-exploit non-renewable resources. These resources aren’t ours to squander; they are a trust fund, in a sense, passed down from previous generations, that we are obligated to protect and pass on.

Investing in the future means rejecting the short-term discounting of non-renewable assets. It means asking: how can we use these resources responsibly today without compromising the ability of tomorrow’s generations to meet their own needs? How can we transition to renewable alternatives so that non-renewable resources are preserved for critical uses that aren’t being replaced?

These are not just environmental questions; they are questions of intergenerational justice.

The third pillar I’m going to talk about is to reimagine our economic model. I don’t know how many economists are sitting in the room. For decades, we have equated growth with progress, measuring success by GDP growth, corporate profits, and material consumption. But this model is costly, unsustainable, and incompatible with planetary survival.

The current system is fuelled by fossil fuel consumption, unregulated resource extraction, and a disregard for ecological limits. And the consequences are very clear: rising global temperatures, melting ice caps, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and the breach of multiple planetary boundaries. The nine planetary boundaries that are well identified by leading scientists are the Earth’s safe operating space for human survival.

So investing in future generations requires a paradigm shift that I’ll talk about soon: from growth at all costs to sustainable, low-carbon economies that operate within planetary limits. This is not about sacrificing prosperity; it’s about redefining it. Prosperity isn’t measured by how much we extract, consume, or produce, but by how well we support human well-being, protect the environment, and ensure intergenerational equity.

Countries around the world are already starting to make this shift. We are seeing investments in renewable energy, circular economies, and sustainable agriculture, for example. We are seeing cities redesigning themselves to be more liveable, more resilient, and less resource-intensive. But we need to go further, faster, and we need a common framework to guide us.

And this brings me to the fourth pillar, which I will emphasise for my talk today: turning our intent into action with innovative, data-driven tools. Because good intentions alone are not enough. We need a way to measure our progress, identify our blind spots, and make evidence-based decisions that align with our intergenerational goals.

That’s why Peking University, where I work, recently launched a project called the Planetary Health Axis System, or PHAS, a groundbreaking AI-driven platform that serves as a digital compass for human sustainable development. Unveiled as a global public good in November 2025, PHAS integrates four core axes—human health, species health, environmental health, and societal health—that are quantified by over 48,000 key variables to dynamically track, for the very first time, human footprints against the planetary boundaries.

What makes PHAS truly transformative is its holistic, solution-oriented design rooted in intergenerational equity and planetary limits. Let me share five key differences between PHAS and traditional models.

First, cross-domain integration. Unlike legacy systems that isolate health and environmental metrics, PHAS links all four axes to reveal complex intergenerational dependence. For example, it can show very quickly and comprehensively how over-extracting water for industry impacts not just freshwater scarcity, which is part of the environmental health, but also increases the risk of water-borne diseases, which is part of human health, and threatens wetland biodiversity, which is part of species health. These connections are often invisible in fragmented tools, but they are critical to making informed decisions.

Second, comprehensive data utilisation. PHAS harnesses global open data from satellite images to medical records, from species migration tracks to economic indicators, to eliminate blind spots. Its AI algorithms ensure data quality and coherence far beyond what traditional statistical models and other AI models can achieve, giving us a complete, real-time picture of our planetary health.

Third, actionable guidance. Many tools stop at identifying risk. They tell us what’s wrong but not how to fix it. PHAS goes beyond that. It delivers policy-ready insights, such as fair allocation of planetary boundary responsibilities via cooperative game methods, to turn insights into practical plans. It doesn’t just ask “what if,” it asks “what now?”

Fourth, intergenerational equity in resource allocation. Unlike conventional tools that discount the value of non-renewable resources for future use, PHAS treats resource allocation between generations as an equitable endeavour. It ensures that our current consumption does not prioritise short-term gains over the long-term viability of non-renewable assets, turning the trust-fund idea into a measurable and actionable principle.

Fifth, planetary boundary constraint analysis. PHAS embeds the nine planetary boundaries as non-negotiable constraints in its modelling. It analyses our current resource use through the lens of the Earth’s safe operating space, helping us avoid transgressing ecological limits that underpin intergenerational survival.

Since its launch, PHAS has rapidly gained global traction. It was officially released at the 2025 World Health Summit in Berlin, and we have already established partnerships with the WHO Hub for Pandemic Preparedness, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Charité Berlin, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, where our teams are actively exploring collaborative initiatives to apply PHAS in planetary health analysis. I hope, in the future, we can work with UNICEF to move this forward.

So in closing, ladies and gentlemen, investing in future generations is a survival imperative. It requires us to transcend short-term gains, value non-renewable assets as irreplaceable trust funds, and align our economies with planetary limits. And it requires us to embrace innovative tools such as PHAS that turn aspirations into measurable progress.

We stand at a critical crossroads. The choices we make today will determine whether Homo sapiens thrives or merely survives. Future generations will judge us by the world we leave them—a world that is healthy, equitable, and sustainable. So let us choose to invest in their future, which is our topic today, knowing our legacy is inseparable from theirs. Let us act with courage and farsight so that Homo sapiens can continue to thrive, not just survive.

Later, if time permits, you are most welcome to watch the nine-minute-long video clip, but I’ll leave that to Henry.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Thank you, Professor Liu, for your very comprehensive and very stimulating sharing as well. Absolutely, we can play the video later after our Q&A. But now we still have some time for Q&A. If any guests have questions for Madam Sande and also Professor Liu, please raise your hand. Oh, yes, the Ambassador from Fiji, please, go ahead.

Robert Lee, Ambassador of Fiji to China

I think I’ll just sit, because I need to look at what I’ve scribbled on this piece of paper, and sometimes I can’t even read my own handwriting. I want to make a comment and a question within that comment. But let me first thank the speakers. I was very enlightened by the speeches, and that’s why I was scribbling things down, and questions started forming in my head. So the topic today was very enlightening for me.

Let me first put into context Fiji. Fiji is a small country. It has less than 1 million people. The indigenous population is about two-thirds, and a migrant population of about one-third, of which the Chinese population is less than 1%. The Indigenous population is traditionally communal in structure, and the resources of land and sea are shared resources. They are not individually owned resources; they are communal resources.

There are about 1,000 villages in Fiji. They live in rural areas. Fiji has about 300 islands and is mainly rural in terms of the indigenous population, with very beautiful beaches, beautiful seas, and undeveloped land. The land is owned collectively by the indigenous people.

So that gives you a sense of what Fiji is. In that context, and coming back to the presentations today, as I listened to it, China and parts of Africa, etc, I was imagining the globe as a country. If it is a single country, then developing countries like Fiji are basically the rural element of this country called Earth, right? And so, the rural part of Earth is migrating to the urban part, which is the developed countries. This migration will forever continue as long as the opportunities in developing countries are not developed.

And how do you define “opportunities” with a resource? If you can’t develop it yourself, it is not really a resource. If it is a resource that only others can develop, then it is a resource that will be forever taken out.

So, as I look at China and I look at the rural areas, these last two years, I’ve been travelling around China quite a lot, and I’ve been specifically visiting rural ethnic villages. Why? Because in the ethnic communities of China, I see Fiji in those communities. Why do I say that? Because in the ethnic communities of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi, I see villages of 200 people to 1,000 people. They have a communal structure, and the village enterprise is a shared enterprise. It is communally structured, with elements of capitalism and socialism. To me, that’s a Chinese characteristic.

Now, when we look at development models from UNICEF, UNIDO, etc., I can say this as a person coming from Fiji, but looking back at Fiji, all the business-school models of enterprise, etc., do not capture a commercial entity based on a communal model. It’s private capital, individualistic, private ownership, individual ownership. You own the shares; those are your shares. It is not a collective share. And so the business models are based on a structure that is, in many ways, not aligned with the traditional communal structure of a village.

So, as I look at development models for a country like Fiji, for us to keep our people in the villages, in the rural areas where the resources are, we need to have commercial enterprises developing from that communal model. And as I look at inclusive development, education, training, etc., if we train and develop capabilities that are not aligned with the development of the village, then that capability is a capability that is marketable worldwide, because it allows that person to migrate, because there is no opportunity in the village.

So my point, therefore, is: the development models must develop for the conditions that countries are in, and I find that in China to be very relevant. I don’t find that in statements by international development partners of developing for you to stay in your village; it’s giving you the capabilities to migrate.

And therefore, for the individual, as a person, if I came from a village, that’s the best model. I love it because I can migrate. For the country, that’s not necessarily the best model, because unless I can develop opportunities, I can’t keep you. So forever, I am a source of migration. For the village and the indigenous population, that is an existential risk, because I am training you to leave the village. The village culture is gone. The resource is there for someone else to come and monetise, because you can’t monetise it—you have left the village. The very essence of your being of a Fijian in a village setting is forever lost.

So I look back at Guizhou and Guangxi and the villages there. If you have forever migration, you lose your culture, you lose your identity, back to the mountains, to the land, to the sea. And that is a risk that I see in terms of inclusive, resilient development. That paradigm has never been addressed, because it is not a paradigm that the world faces. It is the paradigm of a village. And that village, nobody cares about, because you are too small, right? It is not a model that will capture the global attention, because in the whole world, there are only about 600,000 Fijians, and they are only known for their rugby and their smiles, etc.

But to keep a culture existing, to have resilient, inclusive development, whilst we all agree on training, education etc., but unless education and training enable you to develop what you have in your village and in your area, the more we train for a model that is based in the urban area, the more you will lose the cultural identity and the civilization of small communities.

I think in many ways China has addressed that, but at the same time—and this is now where we come into the geopolitical conflicts—China is not to be the model; the West is the model. And this tension is drawing small countries like Fiji, not knowing whether we are on this side or that side. We have the ocean, we are on the land, we see the sea rising, we still live in the sea, but we are on land. And this is a strategic conundrum that we face: we take the Western model, in the daytime we go to work, we are told we are individuals; we come home at night, and we are forced back into our cultural norms and traditions, where we have to share everything. So we go from individual to communal every day—it’s schizophrenia—and that has not been addressed in any development model. So I just made that comment.

Thank you.

Amakobe Sande

Let me just say thank you, Your Excellency. I am absolutely fascinated by what you’ve just said, because I studied participatory development, which is really about engendering development from the perspective of people’s felt realities, context, but also opportunity.

I grew up in a village in Kenya, and now I have migrated to Beijing. Had the opportunities been nurtured and developed back in Kenya, I might have stayed. But I did want to say, it’s good that you talked about China because when I think back to UNICEF’s programs around the world, those programs operate in varied cultural, political, and economic contexts. And so there is a place. I say this because I see a lot of groups come from Africa and around the world to study China’s experience. I sometimes wonder, because China’s experience was developed in a particular governance context that is not necessarily replicable when these groups go back home.

So yes, it’s about development philosophy, development ideology, but I feel it’s fundamentally about a country’s vision. It doesn’t matter who the international players are. What is the country’s vision for its development and the development of its own people? And staying rigidly stuck to maintaining that vision and aligning whatever international support comes along a dedicated path of development and prosperity—that doesn’t often happen. There is a lot of wavering. There is a lot of short-termism and opportunities, rather than the long-range commitment to a path for your own people that isn’t so reliant on the whims and changes of whatever international partnerships may come forth. So I’m agreeing with you, but I’m saying there is really a strong place for country-owned development and aligning international support along that path rather than disparate paths.

And so, where UNICEF is present around the world, it isn’t about bringing a development ideology to the context. It’s about supporting that country to carry its own vision for development. But this is a long debate. Thank you.

Hannes Hanso, Ambassador of Estonia to China

Thank you for this most interesting discussion and topic. So thank you, Henry and Mabel, and the CCG team. It’s always a pleasure to be here. Normally, it’s about the Five-Year Plan, or the Party Congress, or the National People’s Congress, or something like that; now it’s about something more existential. So a pleasure.

I have a question regarding the population growth challenge. Of course, China is not the only country facing this challenge with a declining population. I guess with more prosperity and more education, as a result, essentially you always get a decline in your population. So with the declining birth rates in China, I mean, we hear speculation: what is the reason why families in China simply no longer want to have children? I hear of many cases where people say they don’t want children at all; they don’t want to have a family.

So what we hear is opinions, but has there been some sort of more scientific approach to study what the root causes of this phenomenon are? Is there a study that one can share? This is quite significant, I think, this trend that we see.

There was one of the slides about the direct trajectory with a 20-year delay between Japan and China. That’s very interesting, because in Japan, what has happened is that they have opened their country much more to immigration. Do you think China, in 20 years’ time, will encourage large numbers of foreign workers? And what would that mean? What would the implications in this case be for so many different aspects of social and even political life here? Thank you.

Gordon G. Liu

Well, thank you for raising that question on population growth. I am an economist focused on health economics and population economics, so I know this topic very well. Now you ask what caused population growth to decline? Well, basically, from an economic standpoint, you can think about the causes from the demand standpoint: Why would people need the children? There are a couple of components out there.

Okay, we need the children because we care about our security when we’re old. We care about children because we want to continue our family, if not to continue Homo sapiens. As a result, when modern societies have well-developed social security systems to protect people for much better conditions, over time, that demand will be reduced. Number One. That is what you see: developed countries have much lower fertility rates than developing countries because they don’t need it. And some families like myself, you know, I want my family to continue. That is another component of the demand, which is not that decisive. Some people just don’t really care. They only care about their own generation, not to mention the continuation of Homo sapiens.

So, just to put the long story short, the supply side, which can also explain why the fertility trend will continue, is simply because the cost of childbearing is increasing, especially when women can find much better-paid jobs in the labour market. Why do women have to sacrifice their time at home to bear the cost without husbands to sacrifice? So when women find better opportunities in the modern labour market, that will raise the costs of childbearing and child raising. As a result, that’s the consequence, unless we compensate for women’s sacrifice. But that’s not gonna happen unless the men want to take care of the burden.

So, I can simply pick these two components to explain why the fertility decline will be a long-term trajectory. Period. There’s nothing you can do about it. Now, is that something we have to reverse, or we don’t have to intervene? Well, people have very different opinions. If China ends up with only 600 million people, to me, I’m not so sure if that’s necessarily a bad thing, considering the planetary boundaries that I talked about. You know what I mean? I don’t wanna talk anything more.

Bernard Shwartländer, Co-Chair of the Governing Board and Distinguished Research Professor of Global Health, Peking University Institute for Global Health and Development; Former Global Health Envoy of Germany

Thank you very much. I think especially the last question is probably an utterly defining question for Chinese society, but not only for Chinese society. What we saw in terms of population development—if you look not only at the number of total population, but at the composition of the population, with a majority of people aged 60 and above—the structure of society will be fundamentally different. I think this goes very much to what Amakobe said, and what Gordon, of course, said.

Then the question is really burning, and this is not something you can fix by giving a little money for a woman to buy a stroller and a children’s bed. I mean, I’d be very provocative. This is about fundamental societal insecurity. I think some of what happened in China, this incredible development to prosperity over one or two generations—it got better and better and better, and more money, a better house, and whatever—and suddenly that comes to an end. It levels off because housing is so expensive. Young people living in Beijing on their own salaries have no chance to buy their own house. I’ll say it very bluntly: I couldn’t pay for these houses. I am pretty well established; I couldn’t. That’s the reality. So they can only live off, basically, the wealth that their parents have made, if they are lucky enough to have that. If you are not lucky, you have no chance at all.

These are insecurities, especially for young women, I think. Why would I take that risk? How can I afford it? It’s very deep: how can I afford to have a child for which I cannot guarantee the same opportunities that I may have had?

Unless we address this, and I think this actually goes back to Gordon, what you have said, we need a fundamental paradigm shift in how we define development. Development in the past was at least 80 per cent about GDP. And today, if you open the newspaper and look at development, it is GDP. It’s just crazy.

It is not only about prosperity and well-being—there is not a balance. Unless we shift and say: we need GDP, we need wealth, absolutely, that has made a huge difference—but it has to be in the right balance with other factors, because otherwise, we pay. I think that is the message that Gordon gave.

It’s a long answer, of course, but unless we manage that, and I think that is where this work will be so important, because for the first time, now we are able, with AI and these tools, to look at all factors in one part, all the interrelations in one goal, which is very different from looking into one aspect only: GDP, or health, or climate, or whatever. Put it all together and say: we need a better balance to move forward, because that is how real development will go forward. So I think it’s a long answer, but I feel very passionate about it.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Great. Thank you. Thank you. Bernard was also the former Chief Representative of the WHO in China.

And I also see Minister Song sitting here. You are the former Minister-Counsellor for Economic and Commercial Affairs at the Chinese Embassy in Japan, now a Senior Research Fellow at CCG. The Ambassador has just mentioned Japan’s experience. Japan is now starting to import skilled labour and so on. What do you think about China in the years ahead? Since we are about 20 years behind Japan in terms of an ageing population, what about Japan’s experience now that they are starting to recruit foreign labour? What do you think?

Song Yaoming, Senior Research Fellow, CCG; Former Minister-Counsellor for Economic and Commercial Affairs, Chinese Embassy in Japan

Thank you, Henry. I’m not an expert in this field, I’m sorry. I think both Japan and China have the same population problems. I am very glad to be here with CCG and UNICEF colleagues. I very much admire what UNICEF and your colleagues have done for our children. Children are our future; this is a very important issue for both China and other countries as well. I’m sorry, Henry, I didn’t prepare any detailed comments.

Henry Huiyao Wang

No, I understand. You are in business and trade, and you are from MOFCOM. So what about Mr Han? Mr Han Bing was also the former Deputy Director-General of the Department of European Affairs at MOFCOM.

Han Bing, Senior Research Fellow, CCG; Former Deputy Director-General, Department of European Affairs, Ministry of Commerce

Sorry, I am also not in this field. I am here just to learn from the experts. But just on what Dr Bernard said, that you don’t need to look only at GDP, you need to look at development, you need to look at all aspects of people’s lives. I think the Chinese government already recognises this.

For example, we pay great attention to the environment. Ten years ago, when President Xi visited the Yangtze River, he said that we do not need “big development,” we need “big protection” of the environment. Over these ten years, we have seen the results of this movement. I think that when the Chinese government realises a problem, the government will take policies and measures, and people will follow. So, for me, I am confident that in the future, the situation will change for the better. Thank you.

Henry Huiyao Wang

Okay, so we are almost at the end. It has really been a great honour to have all of you here. I would now like to leave the last remarks to our co-host, Madam Sande.

Amakobe Sande

Let me just say that Your Excellency, Ambassador Hanso, asked a really important question. I think there are a number of low-hanging fruit. There are many for whom hukou reform will make a fundamental difference. 138 million children are affected by migration, 67 million of them physically left behind in the western and rural parts of the country. That will be a big factor in the thinking and the transformation in terms of, first, reuniting families, but also enabling these children to access services wherever they are. So that’s a low-hanging fruit.

Henry emphasised this point. There are also those for whom structural labour policy prohibitions, parental leave, family-friendly workplaces, support for childcare, and free preschooling will have fundamental consequences for how families, individuals, and women visualise whether it is possible to have one more child. So there are low-hanging fruits, and we are pleased that in this particular period, China is implementing what UNICEF would call very positive policies around childcare support, preschooling, and child grants. Some have argued that the levels are low, others have said they are high, but they will have an influence.

To what extent this will dramatically shift fertility and population policies, I have to say, I don’t know. I don’t know what the net result will be in the future. But these policies that are being implemented now are those that UNICEF has pronouncedly supported. We are really looking to ensure, particularly in the western part of the country, as many have alluded to, that we are able to work in partnership to close those last-mile gaps there and really address issues of unbalanced development and the quality and access of services for children there, so that indeed they are able not just to survive, as the Professor was saying, but to thrive.

So thank you very much for the opportunity to engage with all of you today, and thank you to CCG for the partnership in co-hosting today’s engagement.

Transcript of CCG session at Doha Forum: U.S.–China Relations: Navigating the Risks and Opportunities of a Changing Global Order

As part of the Doha Forum 2025, the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), in partnership with the Doha Forum, convened a session titled “U.S.–China Relations: Navigating the Risks and Opportunities of a Changing Global Order.”

Transcript: CCG VIP luncheon on global development cooperation & China's role in it

On September 15, the Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG) hosted its latest CCG VIP Luncheon themed “Global Development Cooperation and the Role of China.”

Transcript: Adam Tooze at CCG

On June 30, 2025, Adam Tooze, Shelby Cullom Davis chair of History at Columbia University, Director of its European Institute, and renowned author of the Chartbook newsletter, visited the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in Beijing for keynote speech, a dialogue with CCG Founder and President Henry Huiyao Wang, and a Q&A session with a live audi…